Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)

390 likes | 898 Vues

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD). Pharm.D Balsam Alhasan. DEFINITION:. Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to a group of ulcerative disorders of the upper GI tract that require acid and pepsin for their formation.

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) Pharm.D Balsam Alhasan

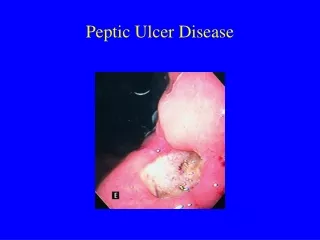

DEFINITION: • Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to a group of ulcerative disorders of the upper GI tract that require acid and pepsin for their formation. • Ulcers differ from gastritis and erosions in that they extend deeper into the muscularismucosa. • The three common forms of peptic ulcers include: • Helicobacter pylori (HP)– associated ulcers, • Nonsteroidalantiinflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced ulcers, • And stress-related mucosal damage (also called stress ulcers).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • The pathogenesis of duodenal ulcers (DU) and gastric ulcers (GU) is multifactorialand most likely reflects a combination of pathophysiologic abnormalities and environmental and genetic factors. • Most peptic ulcers occur in the presence of acid and pepsin when HP, NSAIDs, or other factors disrupt normal mucosal defense and healing mechanisms. • Acid is an independent factor that contributes to disruption of mucosal integrity. Increased acid secretion has been observed in patients with DU and may result from HP infection. Patients with GU usually have normal or reduced rates of acid secretion.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (Cont.) • Alterationsin mucosal defense induced by HP or NSAIDs are the most important cofactors in peptic ulcer formation. Mucosal defense and repair mechanisms include mucus and bicarbonate secretion, intrinsic epithelial cell defense, and mucosal blood flow. Maintenance of mucosal integrity and repair is mediated by endogenous prostaglandin production.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (Cont.) • HP infection causes gastritis in all infected individuals and is causally linked to PUD. However, only about 20% of infected persons develop symptomatic PUD. Most non-NSAID ulcers are infected with HP, and HP eradicationmarkedly decreases ulcer recurrence. HP may cause ulcers by direct mucosal damage, altering the immune/inflammatory response, and by hypergastrinemia leading to increased acid secretion.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (Cont.) • Nonselective NSAIDs (including aspirin) cause gastric mucosal damageby two mechanisms: • (1) A direct or topical irritation of the gastric epithelium, and • (2) Systemic inhibition of the cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) enzyme, which results in decreased synthesis of protective prostaglandins. • Use of corticosteroids alone does not increase the risk of ulcer or complications, but ulcer risk is doubled in corticosteroid users taking NSAIDs concurrently.

Other Factors: • Epidemiologic evidence links cigarette smoking to PUD, impaired ulcer healing, and ulcer-related GI complications. • The risk is proportional to the amount smoked per day. • Although clinical observation suggests that ulcer patients are adversely affected by stressful life events, controlled studies have failed to document a cause-and-effect relationship.

Other Factors: • Coffee, tea, cola beverages, beer, milk, and spices may cause dyspepsiabut do not increase PUD risk. Ethanol ingestion in high concentrations is associated with acute gastric mucosal damage and upper GI bleeding but is not clearly the cause of ulcers.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION • Abdominal pain is the most frequent symptom of PUD. The pain is often epigastricand described as burning but can present as vague discomfort, abdominal fullness, or cramping. • A typical nocturnal pain may awaken patients from sleep, especially between 12 AM and 3 AM. • Pain from DU often occurs 1 to 3 hours after meals and is usually relieved by food, whereas food may precipitate or accentuate ulcer pain in GU.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION • Antacids provide rapid pain relief in most ulcer patients. • Heartburn, belching, and bloating often accompany the pain. • Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are more common in GU than DU. • The severity of symptoms varies from patient to patient and may be seasonal, occurring more frequently in the spring or fall.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION • Pain does not always correlate with the presence of an ulcer. • Asymptomaticpatients may have an ulcer at endoscopy, and patients may have persistent symptoms even with endoscopically proven healed ulcers. Many patients (especially older adults) with NSAID-induced, ulcer-related complications have no prior abdominal symptoms.

Complications: • Complications of ulcers caused by HP and NSAIDs include: • Upper GI bleeding, • Perforation into the peritoneal cavity, • Penetration into an adjacent structure (e.G., Pancreas, biliary tract, or liver), • And gastric outlet obstruction. • Bleeding may be occult or present as melena or hematemesis.

Complications: • Perforation is associated with sudden, sharp, severe pain, beginning first in the epigastrium but quickly spreading over the entire abdomen. • Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction typically occur over several months and include early satiety, bloating, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss.

DIAGNOSIS • The physical examination may reveal epigastric tenderness between the umbilicus and the xiphoid process that less commonly radiates to the back. • Routine laboratory tests are not helpful in establishing a diagnosis of uncomplicatedPUD. The hematocrit, hemoglobin, and stool hemoccult tests are used to detect bleeding.

Diagnostic Procedures: • The diagnosis of HP infection can be made using endoscopic or nonendoscopic tests. The tests that require upper endoscopy are invasive, more expensive, uncomfortable, and usually require a mucosal biopsy for histology, culture, or detection of urease activity. • The nonendoscopic tests include serologic antibody detection tests, the urea breath test (UBT), and the stool antigen test.

Diagnostic Procedures: • Serologic tests detect circulating immunoglobulin G directed against HP but are of limited value in evaluating post-treatment eradication. • The UBT is based on urease production by HP. • Testing for HP is only recommended if eradication therapy is considered.

Diagnostic Procedures: • If endoscopy is not planned, serologic antibody testing is reasonable to determine HP status. The UBT is the preferred nonendoscopic method to verify HP eradication after treatment. • The diagnosis of PUD depends on visualizing the ulcer crater either by upper GI radiography or endoscopy. Radiography may be the preferred initial diagnostic procedure in patients with suspected uncomplicated PUD.

Diagnostic Procedures: • Upper endoscopy should be performed if complications are thought to exist or if an accurate diagnosis is warranted. If a GU is found on radiography, malignancy should be excluded by direct endoscopic visualization and histology.

DESIRED OUTCOME • The goals of treatment are relieving ulcer pain, healing the ulcer, preventing ulcer recurrence, and reducing ulcer-related complications. • In HP positive patients with an active ulcer, a previously documented ulcer, or a history of an ulcer-related complication, the goals are to eradicate the organism, heal the ulcer, and cure the disease with a cost-effective drug regimen.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT • Patients with PUD should eliminate or reduce psychological stress, cigarette smoking, and the use of nonselective NSAIDs (including aspirin). If possible, alternative agents such as acetaminophen, a nonacetylated salicylate (e.g., salsalate), or a COX-2 selective inhibitor should be used for pain relief. • Although there is no need for a special diet, patients should avoid foods and beverages that cause dyspepsia or exacerbate ulcer symptoms (e.g., spicy foods, caffeine, alcohol).

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT • Eradication of HP is recommended for HP-infected patients with GU, DU, ulcer-related complications, and in some other situations. Treatment should be effective, well tolerated, easy to comply with, and cost-effective (Table 29-1).

Therapeutic Options: • First-line eradication therapy is a proton pump inhibitor (PPI)–based, three-drug regimen containing two antibiotics, usually clarithromycin and amoxicillin, reserving metronidazole for back-up therapy (e.g., clarithromycin– metronidazole in penicillin-allergic patients). The PPI should be taken 30 to 60 minutes before a meal along with the two antibiotics.

Therapeutic Options: • Although an initial 7-day course provides minimally acceptable eradication rates, longer treatment periods (10 to 14 days) are associated with higher eradication rates and less antimicrobial resistance. • First-line treatment with quadruple therapy using a PPI (with bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline) achieves similar eradication rates as PPIbased triple therapy and permits a shorter treatment duration (7 days).

However, this regimen is often recommended as second-linetreatment when a clarithromycin–amoxicillin regimen is used initially. All medications except the PPI should be taken with meals and at bedtime.

Failed Eradication: • If the initial treatment fails to eradicate HP, second-line empiric treatment should: • (1) use antibiotics that were not included in the initial regimen; • (2) include antibiotics that do not have resistance problems; • (3) use a drug that has a topical effect (e.g., bismuth); and • (4) be extended to 14 days. • Thus, if a PPI–amoxicillin–clarithromycin regimen fails, therapy should be instituted with a PPI, bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 14 days.

Conventional Protocols: • Treatment with a conventional antiulcer drug (e.g., PPI, histamine-2 receptor antagonist [H2RA], or sucralfate alone is an alternative to HP eradication but is discouraged because of the high rate of ulcer recurrence and ulcer-related complications. • Dual therapy (e.g., H 2RA plus sucralfate, H2RA plus PPI) is not recommended because it increases cost without enhancing efficacy.

Maintenance therapy: • Maintenance therapy with a PPI or H2RA (Table 29-2) is recommended for high-risk patients with ulcer complications, patients who fail HP eradication, and those with HP-negative ulcers. • For treatment of NSAID-induced ulcers, nonselective NSAIDs should be discontinued (when possible) if an active ulcer is confirmed. • Most uncomplicated NSAID-induced ulcers heal with standard regimens of an H2RA, PPI, or sucralfate(see Table 29-2) if the NSAID is discontinued.

Patients on NSAIDs: • If the NSAID must be continued, consideration should be given to reducing the NSAID dose or switching to acetaminophen, a nonacetylated salicylate, a partially selective COX-2 inhibitor, or a selective COX-2 inhibitor. • PPIs are the drugs of choice when NSAIDs must be continued because potent acid suppression is required to accelerate ulcer healing. If HP is present, treatment should be initiated with an eradication regimen that contains a PPI.

Special Cases: • Patients at risk of developing serious ulcer-related complications while on NSAIDs should receive prophylactictherapy with misoprostol or a PPI. • Patients with ulcers refractory to treatment should undergo upper endoscopy to confirm a nonhealing ulcer, exclude malignancy, and assess HP status. • HP-positive patients should receive eradication therapy. In HP negative patients, higher PPI doses (e.g., omeprazole 40 mg/day) heal the majority of ulcers. Continuous PPI treatment is often necessary to maintain healing.

Evaluation Of Therapeutic Outcomes: • Patients should be monitored for symptomatic relief of ulcer pain as well as potential adverse effects and drug interactions related to drug therapy. • Ulcer pain typically resolves in a few days when NSAIDs are discontinued and within 7 days upon initiation of antiulcer therapy. • Most patients with uncomplicatedPUD will be symptom-free after treatment with any one of the recommended antiulcer regimens.

Evaluation Of Therapeutic Outcomes: • The persistence or recurrence of symptoms within 14 days after the end of treatment suggests failure of ulcer healing or HP eradication, or an alternative diagnosis such as gastroesophageal reflux disease. • Most patients with uncomplicated HP-positive ulcers do not require confirmation of ulcer healing or HP eradication.

Evaluation Of Therapeutic Outcomes: • High-risk patients on NSAIDs should be closely monitored for signs and symptoms of bleeding, obstruction, penetration, and perforation. • Follow-up endoscopy is justified in patients with frequent symptomatic recurrence, refractorydisease, complications, or suspected hypersecretory states.