Speech Synthesis

460 likes | 674 Vues

Speech Synthesis. April 14, 2009. Some Reminders. Final Exam is next Monday: In this room (I am looking into changing the start time to 9 am.) I have a review sheet for you (to hand out at the end of class). Exemplar Categorization.

Speech Synthesis

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Speech Synthesis April 14, 2009

Some Reminders • Final Exam is next Monday: • In this room • (I am looking into changing the start time to 9 am.) • I have a review sheet for you (to hand out at the end of class).

Exemplar Categorization • Stored memories of speech experiences are known as traces. • Each trace is linked to a category label. • Incoming speech tokens are known as probes. • A probe activates the traces it is similar to. • Note: amount of activation is proportional to similarity between trace and probe. • Traces that closely match a probe are activated a lot; • Traces that have no similarity to a probe are not activated much at all.

Echoes from the Past • The combined average of activations from exemplars in memory is summed to create an echo of the perceptual system. • This echo is more general features than either the traces or the probe. • Inspiration: Francis Galton

Exemplar Categorization II • For each category label… • The activations of the traces linked to it are summed up. • The category with the most total activation wins. • Note: we use all exemplars in memory to help us categorize new tokens. • Also: any single trace can be linked to different kinds of category labels. • Test: Peterson & Barney vowel data • Exemplar model classified 81% of vowels correctly. • Remember: humans got 94%; protoype model got 51%.

Exemplar Predictions • Point: all properties of all exemplars play a role in categorization… • Not just the “definitive” ones. • Prediction: non-invariant properties of speech categories should have an effect on speech perception. • E.g., the voice in which a [b] is spoken. • Or even the room in which a [b] is spoken. • Is this true? • Palmeri et al. (1993) tested this hypothesis with a continuous word recognition experiment…

Continuous Word Recognition • In a “continuous word recognition” task, listeners hear a long sequence of words… • some of which are new words in the list, and some of which are repeats. • Task: decide whether each word is new or a repeat. • Twist: some repeats are presented in a new voice; • others are presented in the old (same) voice. • Finding: repetitions are identified more quickly and more accurately when they’re presented in the old voice. • Implication: we store voice + word info together in memory.

Our Results • Continuous word recognition scores: • New items correctly recognized: 96.6% • Repeated items correctly recognized: 84.5% • Of the repeated items: • Same voice: 95.0% • Different voice: 74.1% • After 10 intervening stimuli: • Same voice: 93.6% • Different voice: 70.0% • General finding: same voice effect does not diminish over time.

More Interactions • Another task (Nygaard et al., 1994): • train listeners to identify talkers by their voices. • Then test the listeners’ ability to recognize words spoken in noise by: • the talkers they learned to recognize • talkers they don’t know • Result: word recognition scores are much better for familiar talkers. • Implication: voice properties influence word recognition. • The opposite is also true: • Talker identification is easier in a language you know.

Variability in Learning • Caveat: it’s best not to let the relationship between words and voices get too close in learning. • Ex: training Japanese listeners to discriminate between /r/ and /l/. • Discrimination training on one voice: no improvement. (Strange and Dittman, 1984) • Bradlow et al. (1997) tried: • training on five different voices • multiple phonological contexts (onset, coda, clusters) • 4 weeks of training (with monetary rewards!) • Result: improvement!

Variability in Learning • General pattern: • Lots of variability in training better classification of novel tokens… • Even though it slows down improvement in training itself. • Variability in training also helps perception of synthetic speech. (Greenspan et al., 1988) • Another interesting effect: dialect identification (Clopper, 2004) • Bradlow et al. (1997) also found that perception training (passively) improved production skills…

Perception Production • Japanese listeners performed an /r/ - /l/ discrimination task. • Important: listeners were told nothing about how to produce the /r/ - /l/ contrast • …but, through perception training, their productions got better anyway.

Exemplars in Production • Goldinger (1998): “shadowing” task. • Task 1--Production: • A: Listeners read a word (out loud) from a script. • B: Listeners hear a word (X), then repeat it. • Finding: formant values and durations of (B) productions match the original (X) more closely than (A) productions. • Task 2--Perception: AXB task • A different group of listeners judges whether X (the original) sounds more like A or B. • Result: B productions are perceptually more similar to the originals.

Shadowing: Interpretation • Some interesting complications: • Repetition is more prominent for low frequency words… • And also after shorter delays. • Interpretation: • The “probe” activates similar traces, which get combined into an echo. • Shadowing imitation is a reflection of the echo. • Probe-based activation decays quickly. • And also has more of an influence over smaller exemplar sets.

Moral of the Story • Remember--categorical perception was initially used to justify the claim that listeners converted a continuous signal into a discrete linguistic representation. • In reality, listeners don’t just discard all the continuous information. • (especially for sounds like vowels) • Perceptual categories have to be more richly detailed than the classical categories found in phonology textbooks. • (We need the details in order to deal with variability.)

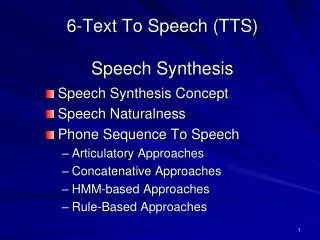

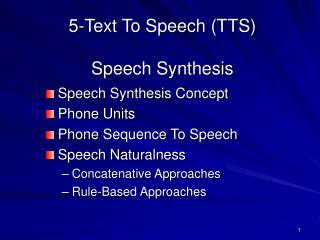

Speech Synthesis:A Basic Overview • Speech synthesis is the generation of speech by machine. • The reasons for studying synthetic speech have evolved over the years: • Novelty • To control acoustic cues in perceptual studies • To understand the human articulatory system • “Analysis by Synthesis” • Practical applications • Reading machines for the blind, navigation systems

Speech Synthesis:A Basic Overview • There are four basic types of synthetic speech: • Mechanical synthesis • Formant synthesis • Based on Source/Filter theory • Concatenative synthesis • = stringing bits and pieces of natural speech together • Articulatory synthesis • = generating speech from a model of the vocal tract.

1. Mechanical Synthesis • The very first attempts to produce synthetic speech were made without electricity. • = mechanical synthesis • In the late 1700s, models were produced which used: • reeds as a voicing source • differently shaped tubes for different vowels

Mechanical Synthesis, part II • Later, Wolfgang von Kempelen and Charles Wheatstone created a more sophisticated mechanical speech device… • with independently manipulable source and filter mechanisms.

Mechanical Synthesis, part III • An interesting historical footnote: • Alexander Graham Bell and his “questionable” experiments with his dog. • Mechanical synthesis has largely gone out of style ever since. • …but check out Mike Brady’s talking robot.

The Voder • The next big step in speech synthesis was to generate speech electronically. • This was most famously demonstrated at the New York World’s Fair in 1939 with the Voder. • The Voder was a manually controlled speech synthesizer. • (operated by highly trained young women)

Voder Principles • The Voder basically operated like a vocoder. • Voicing and fricative source sounds were filtered by 10 different resonators… • each controlled by an individual finger! • Only about 1 in 10 had the ability to learn how to play the Voder.

The Pattern Playback • Shortly after the invention of the spectrograph, the pattern playback was developed. • = basically a reverse spectrograph. • Idea at this point was still to use speech synthesis to determine what the best cues were for particular sounds.

2. Formant Synthesis • The next synthesizer was PAT (Parametric Artificial Talker). • PAT was a parallel formant synthesizer. • Idea: three formants are good enough for intelligble speech. • Subtitles: What did you say before that? Tea or coffee? What have you done with it?

2. Formant Synthesis, part II • Another formant synthesizer was OVE, built by the Swedish phonetician Gunnar Fant. • OVE was a cascade formant synthesizer. • In the ‘50s and ‘60s, people debated whether parallel or cascade synthesis was better. • Weeks and weeks of tuning each system could get much better results:

Synthesis by rule • The ultimate goal was to get machines to generate speech automatically, without any manual intervention. • synthesis by rule • A first attempt, on the Pattern Playback: • (I painted this by rule without looking at a spectrogram. Can you understand it?) • Later, from 1961, on a cascade synthesizer: • Note: first use of a computer to calculate rules for synthetic speech. • Compare with the HAL 9000:

Parallel vs. Cascade • The rivalry between the parallel and cascade camps continued into the ‘70s. • Cascade synthesizers were good at producing vowels and required fewer control parameters… • but were bad with nasals, stops and fricatives. • Parallel synthesizers were better with nasals and fricatives, but not as good with vowels. • Dennis Klatt proposed a synthesis (sorry): • and combined the two…

KlattTalk • KlattTalk has since become the standard for formant synthesis. (DECTalk) • http://www.asel.udel.edu/speech/tutorials/synthesis/vowels.html

KlattVoice • Dennis Klatt also made significant improvements to the artificial voice source waveform. • Perfect Paul: • Beautiful Betty: • Female voices have remained problematic. • Also note: lack of jitter and shimmer

LPC Synthesis • Another method of formant synthesis, developed in the ‘70s, is known as Linear Predictive Coding (LPC). • Here’s an example: • As a general rule, LPC synthesis is pretty lousy. • But it’s cheap! • LPC synthesis greatly reduces the amount of information in speech… • To recapitulate childhood: http://www.speaknspell.co.uk/

Filters + LPC • One way to understand LPC analysis is to think about a moving average filter. • A moving average filter reduces noise in a signal by making each point equal to the average of the points surrounding it. yn = (xn-2 + xn-1 + xn + xn+1 + xn+2) / 5

Filters + LPC • Another way to write the smoothing equation is • yn = .2*xn-2 + .2*xn-1 + .2*xn + .2*xn+1 + .2*xn+2 • Note that we could weight the different parts of the equation differently. • Ex: yn = .1*xn-2 + .2*xn-1 + .4*xn + .2*xn+1 + .1*xn+2 • Another trick: try to predict future points in the waveform on the basis of only previous points. • Objective: find the combination of weights that predicts future points as perfectly as possible.

Deriving the Filter • Let’s say that minimizing the prediction errors for a certain waveform yields the following equation: • yn = .5*xn - .3*xn-1 + .2*xn-2 - .1*xn-3 • The weights in the equation define a filter. • Example: how would the values of y change if the input to the equation was a transient where: • at time n, x = 1 • at all other times, x = 0 • Graph y at times n to n+3.

Decomposing the Filter • Putting a transient into the weighted filter equation yields a new waveform: • The new equation reflects the weights in the equation. • We can apply Fourier Analysis to the new waveform to determine its spectral characteristics.

LPC Spectrum • When we perform a Fourier Analysis on this waveform, we get a very smooth-looking spectrum function: LPC spectrum Original spectrum • This function is a good representation of what the vocal tract filter looks like.

LPC Applications • Remember: the LPC spectrum is derived from the weights of a linear predictive equation. • One thing we can do with the LPC-derived spectrum is estimate formant frequencies of a filter. • (This is how Praat does it) • Note: the more weights in the original equation, the more formants are assumed to be in the signal. • We can also use that LPC-derived filter, in conjunction with a voice source, to create synthetic speech. • (Like in the Speak & Spell)

3. Concatenative Synthesis • Formant synthesis dominated the synthetic speech world up until the ‘90s… • Then concatenative synthesis started taking over. • Basic idea: string together recorded samples of natural speech. • Most common option: “diphone” synthesis • Concatenated bits stretch from the middle of one phoneme to the middle of the next phoneme. • Note: inventory has to include all possible phoneme sequences • = only possible with lots of computer memory.

Concatenated Samples • Concatenated synthesis tends to sound more natural than formant synthesis. • (basically because of better voice quality) • Early (1977) combination of LPC + diphone synthesis: • LPC + demisyllable-sized chunks (1980): • More recent efforts with the MBROLA synthesizer: • Also check out the Macintalk Pro synthesizer!

Recent Developments • Contemporary concatenative speech synthesizers use variable unit selection. • Idea: record a huge database of speech… • And play back the largest unit of speech you can, whenever you can. • Interesting development #2: synthetic voices tailored to particular speakers. • Check it out:

4. Articulatory Synthesis • Last but not least, there is articulatory synthesis. • Generation of acoustic signals on the basis of models of the vocal tract. • This is the most complicated of all synthesis paradigms. • (we don’t understand articulations all that well) • Some early attempts: • Paul Boersma built his own articulatory synthesizer… • and incorporated it into Praat.

Synthetic Speech Perception • In the early days, speech scientists thought that synthetic speech would lead to a form of “super speech” • = ideal speech, without any of the extraneous noise of natural productions. • However, natural speech is always more intelligible than synthetic speech. • And more natural sounding! • But: perceptual learning is possible. • Requires lots and lots of practice. • And lots of variability. (words, phonemes, contexts) • An extreme example: blind listeners.

More Perceptual Findings Reducing the number of possible messages dramatically increases intelligibility.

More Perceptual Findings 2. Formant synthesis produces better vowels; • Concatenative synthesis produces better consonants (and transitions) 3. Synthetic speech perception uses up more mental resources. • memory and recall of number lists • Synthetic speech perception is a lot easier for native speakers of a language. • And also adults. 5. Older listeners prefer slower rates of speech.

Audio-Visual Speech Synthesis • The synthesis of audio-visual speech has primarily been spearheaded by Dominic Massaro, at UC-Santa Cruz. • “Baldi” • Basic findings: • Synthetic visuals can induce the McGurk effect. • Synthetic visuals improve perception of speech in noise • …but not as well as natural visuals. • Check out some samples.

Further Reading • In case you’re curious: • http://www.cs.indiana.edu/rhythmsp/ASA/Contents.html • http://www.acoustics.hut.fi/publications/files/theses/lemmetty_mst/contents.html