Experiments and Quasi-Experiments

440 likes | 666 Vues

Experiments and Quasi-Experiments. Josh Lerner Empirical Methods in Corporate Finance. The problem. Corporate finance has not traditionally carefully thought about: Reverse causation. Impact of unobserved third factors. Even when acknowledge, often responses are inadequate:

Experiments and Quasi-Experiments

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Experiments and Quasi-Experiments Josh Lerner Empirical Methods in Corporate Finance

The problem • Corporate finance has not traditionally carefully thought about: • Reverse causation. • Impact of unobserved third factors. • Even when acknowledge, often responses are inadequate: • E.g., Kaplan-Ruback [1995].

Understandable • In education and labor, there are: • Lots of decisions. • Relatively minor stakes. • Desire to appear innovative: • At least in education. • Larger stakes, greater risk aversion in finance: • Hard to get CEOs, I-bankers to agree to randomized IPOs.

Consequences • Lots of papers about correlation… • Relatively limited number that decisively show causation. • As a result… • Will focus here on experiments to address the issues. • Somewhat different approach.

Strengths of experiments • Allows careful design of choices. • True randomization of participants. • Limited worries about sample selection and other issues.

Limitations of experiments • Short time frame and little study compared to real-world choice. • Are student participants representative? • Modest, low-powered financial stakes. • Role of human subjects committee: • The cancelled pencil orders.

Agenda • Will examine variety of approaches: • From less to more practical in finance context.

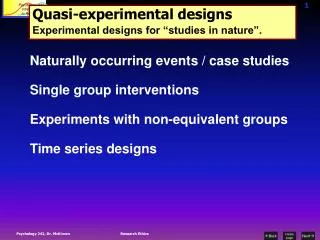

Using Randomization in Development Economics Research Duflo, Glennerster, and Kremer Working Paper

Case for experimentation • Many things may be different: • Legal regime. • Economic conditions. • Skill level. • These are likely to be correlated with “treatment.” • A study of treated and untreated may thus reflect other influences.

Case for experimentation (2) • With experiment, have otherwise identical people: • Allows one to capture treatment effect… • While minimizing bias associated with selection effect.

Other biases • In traditional studies, likely to have data snooping issues: • Many regressions run, but only a few reported. • Playing with controls and sub-samples. • Less opportunities with experiments: • But still sub-sample issues. • FDA bans in clinical trials.

Implementation • In development, can be done fairly cheaply: • Groups are often searching for solutions. • Many programs encounter excess demand. • In many cases, programs are phased in over time • More challenging in corporate finance.

Practical issues • Changes are often done in packages: • Makes it harder to assess impact of any change. • May deviate from perfect experiment: • Selection may be partially non-random. • Participation may not be universal. • Statistical approaches may partially adjust here. • Knowledge spillovers to others.

Generality • Experiments by definition are micro in scope: • Overall effects may be different: • Shifts in pricing, externalities, etc. • “Hawthorne” effect: • Those in experiment may react to being selected, as do those not selected. • Specificity of particular context.

Can experiments work in finance? • In many cases, no: • Size of stakes. • Limited number of players. • Differences in needs across firms. • Risk aversion. • Cost of implementation.

Possible settings • Public programs: • More emphasis on evaluation. • Angel groups, and other young firm financiers: • Mixture of motivations?! • Laboratory experiments that capture essence of problem: • Next paper is an example.

Is Pay-for-Performance Detrimental to Innovation? Ederer and Manso Working Paper, 2008

Split view on incentives and innovation • Number of economics papers showing power of incentive schemes: • Typically, basic production activity. • Experimental methodology. • Negative view in psychology literature of impact on creativity.

Methodology • Use HBS’s CLER laboratory. • 379 subjects. • 60 minute experiment: • 20 periods. • Students paid between $11 and $40, depending on success.

Methodology (2) • Make choices regarding running lemonade stand in each period. • Choose one of three locations (school—most profitable, stadium, and business district), and sugar level, lemon level, color and price. • Different optimum for each location. • Suggest initially a non-optimal strategy (business district): • Participants can fine-tune or radically alter.

Methodology (3) • Three compensation schemes: • Fixed wage per period. • Expect will explore the least. • 50% of profits throughout. • 50% of profits in last 10 periods (exploration). • Expect will explore more and get closer to optimum.

Results • Most likely to sell in school if exploration contract. • Figure 1. • Most likely to explore in early periods if exploration contract. • Figure 2.

Searching performance • Look at for those exploring (leave the business district), when stop (return or converge to a narrow band): • Longer for exploration contract. • Especially for first ten periods. • Especially when also if punitive feature of insufficient profits. • Table 1.

More results • Better record keeping with incentive pay: • Figure 3. • More profits with exploration contract: • Figure 4.

Assessment and concerns • Suggests contracts can effect innovation: • Truth in both views. • But remaining questions: • Would real stakes introduce more risk aversion? • Do incentives really work in real world like this? • Then why are researcher contracts so flat? • What about joint production functions?

The Importance of Holdup in Contracting: Evidence from a Field Experiment Iyer and Schoar Working Paper, 2008

Here, real stakes • Send entrepreneurs to pen market in Chennai, India (>100 shops). • Ordered either generic or custom pens. • Looked at levels of deposit required, as well as reaction to cancellation. • Seeks to test theories of hold-up and renegotiation.

Methodology • Real entrepreneurs used, so familiar with bargaining: • Control for ethnicity, etc. • Push to complete a deal, according to a script (e..g, deposit required). • Randomization in order size and other variables. • Average about $25. • Cancellations done via phone.

Key findings • 25% larger deposit required for customized pens. • If cancel order ex post, more willingness to renegotiate if… • Lower deposit. • Customized pens.

Comments • Closer to real business situation: • Developing country setting allows to replicate real interactions. • Though pressure to get real bargain for analysis. • But may wonder whether more sophisticated parties, bigger stakes, would affect results.

Does Microfinance Really Help the Poor? Morduch Working Paper

Regression discontinuity design • Units are assigned to conditions based on a cutoff score. • The effect is measured as the discontinuity between treatment and control regression lines at the cutoff: • It is not the group mean difference.

RD design, no effect 8 0 7 0 6 0 l l u n 5 0 t s o P 4 0 3 0 Cutoff 2 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 0 3 0 4 0 5 0 6 0 7 0 8 0 9 0 1 0 0 P r e

8 0 7 0 6 0 f f e t s 5 0 o P 4 0 3 0 2 0 0 1 0 2 0 3 0 4 0 5 0 6 0 7 0 8 0 9 0 1 0 0 P r e RD design with effect Cutoff

RD design with effect Difference between groups 8 0 Control group regression line 7 0 Treatment group regression line 6 0 f f e t s 5 0 o p 4 0 3 0 Cutoff 2 0 0 1 0 2 0 3 0 4 0 5 0 6 0 7 0 8 0 9 0 1 0 0 P r e

Trade-off • When properly implemented and analyzed, RD yields an unbiased estimate of treatment effect: • it is reasonable to assume that in the absence of the treatment, there would be no discontinuities that naturally occurs between the two groups.

Trade-off (2) • Statistical power is considerably less than a randomized experiment of the same size. • Effects are unbiased only if the functional form of the relationship between the assignment variable and the outcome variable is correctly modeled: • E.g., non-linearities.

Assessment • Cook, Shaidsh and Wong [2006]: • Regression discontinuity studies in education do as well as experiments. • But other approaches do not: • Differences-in-differences. • Careful controls. • Other studies suggest dramatic advantages to experiments (e.g., of peer effects).

Application to finance • In many cases, seem like appropriate design, e.g.: • Securities regulation cut-offs. • Subsidies for small firms. • Avoidance of many problems illustrated above.

Paper illustrates remaining difficulties • Seek to understand impact of microfinance: • In Bangladesh, half-acre cut-off for participation. • But rules appear to be broken: • See Table 1, Figure 2.

Paper illustrates remaining difficulties (2) • As a result, need to divide villages by whether microfinance was available there. • Ends up more like a differences-in-differences approach.

Lessons • This approach seems very reasonable: • Better fit for corporate finance. • But messy reality has to be grappled with. • And limited power of tests may be problematic.

Final thoughts • Corporate finance has been surprisingly casual about these issues. • Addressing causality issues is quite important. • Practical limitations of many approaches used elsewhere… • But more can be done!