Evolution of Fluoride Toothpastes: From Ashes to Advanced Formulations

410 likes | 467 Vues

Learn about the history, components, and effectiveness of fluoride toothpastes, from ancient practices to modern formulations. Understand the role of abrasives, detergents, humectants, flavoring, preservatives, and active agents. Explore the development of fluoride compounds and their impact on oral health.

Evolution of Fluoride Toothpastes: From Ashes to Advanced Formulations

E N D

Presentation Transcript

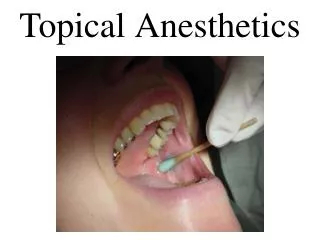

Home-applied topical fluoride Dr. Ahmad Aljafari

Lecture outline • Introduction • Fluoride toothpastes • History • Components • Evidence for effectiveness • Fluoride mouthwashes • Types and components • Evidence for effectiveness • Recommendations the use of fluoride toothpaste and mouthwash

Methods for fluoride delivery • Fluoridated water. • Fluoridated foods (salt, milk). • Fluoride supplements. • Home applied topical fluoride. • Fluoride in dental materials. • Professionally applied fluoride.

Systemic vs. Topical • Fluoride incorporated during tooth development is insufficient to play a significant role in caries prevention. • The topical effect of fluoride surrounding the enamel is most important.

History of toothpastes • The use of toothpaste to cleanse teeth and gums dates back as far as 5000 B.C. • Egyptians used ashes of oxen hooves, burned egg shells, and pumice. • The Greeks used crushed bones and oyster shells. • The Romans added more flavoring to help with bad breath, as well as powdered charcoal and bark. • The Chinese used a wide variety of substances over time that have included ginseng, herbal mints and salt.

History of toothpastes • Modern toothpastes started to be developed in the 1800s, they were mostly powdered. • Early versions contained soap, chalk, Betel nut, and ground charcoal. • During the 1850s, a new toothpaste in a jar called a “Crème Dentifrice” was developed. • In 1873 Colgate started the mass production of toothpaste in jars. • In the 1890s, Colgate introduced toothpaste in a tube similar to modern-days.

History of toothpastes • In 1945, soap was replaced by other ingredients such as sodium laurylsulphate to make the paste into a smooth paste. • Fluoride was added to toothpastes to help prevent dental caries as early as 1914. • However, fluoridated toothpastes were not commercially available until the 1960’s. • By the end of the 1970’s, 95% of toothpaste market shares were taken by fluoridated toothpaste. • Today, toothbrushing is the most widely used method of applying fluoride

Components of toothpaste • Modern toothpaste contains the following: • Abrasives • Detergents • Humectants • Flavouring • Preservatives • Active agents

Abrasives • Constitute 10-50% of toothpaste content. • Play an active role since they mechanically remove food debris, plaque and calculus. • Technically considered an inactive ingredient because they don't reduce the risk of dental caries or periodontal disease. • Examples: alumina, hydrated silica, dicalcium phosphate, salt, pumice, kaolin, bentonite, calcium carbonate (chalk), sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), calcium pyrophosphate

Detergents • Constitute 0.5-2% of toothpaste content. • Also known as soaps, foaming agents, or surfactants. • Aid in the removal of compounds that have properties different from one another (e.g. oil and water). • Require the addition of flavouring to mask their bad taste. • Examples:sodium laurylsulfate (SLS), sodium lauroylsarcosinate, sodium N-laurylsarcosinate, dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, sodium stearylfumarate, sodium stearyl lactate, sodium laurylsulfoacetate

Humectants • Constitute 15-70% of toothpaste content. • Retain water to maintain a consistent paste-like quality. • Prevent the separation of liquids and solids. • Can affect flavour, coolness and sweetness. Examples:sorbitol, pentatol, glycerol, glycerin, propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol, water, xylitol

Flavouring • Constitute 0.8-1.5% of toothpaste content. • Mask the flavour of fluoride and the detergent components, especially SLS. • Mint flavours, especially when combined with menthol, contain oils that volatilize in the mouth. • The volatilization requires energy - extracted from the tissues of the mouth as heat, giving a cooling sensation. • Examples: peppermint, spearmint, cinnamon, wintergreen, and menthol, fennel

Preservatives • prevent the growth of microorganisms in toothpaste • Examples: sodium benzoate, methyl paraben, ethyl paraben

Active agents • Components that have a direct effect on the teeth or gums. • must be blended in a way that their activity is not lost.

Active agents • Fluoride, calcium glycerophosphate, xylitol – Caries prevention • Sodium pyrophosphate – Anti-calculus agent • strontium chloride, potassium citrate - Desensitizing agents • Triclosan, zinc citrate, chlorhexidene, xylitol – Anti-plaque agents

Fluoride compounds • Sodium fluoride: • The simplest fluoride compound, very soluble in water. • The first fluoride compound to be added to toothpaste. • Was not compatible with most of early types of abrasives. • Compatible with newer abrasives (e.g. Silica). • Nowadays as effective as other fluoride agents.

Fluoride compounds • Acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF): • Lab experiments showed that more fluoride was incorporated into enamel when the fluoride-containing solution was acidified. • Results of clinical trials were mixed – production discontinued. • APF has been the compound of choice in fluoride-containing gels.

Fluoride compounds • Stannous fluoride: • Was used with calcium pyrophosphate as an abrasive. • The Abrasive slowly inactivated the fluoride. Stannous fluoride would hydrolyse to ineffective stannic fluoride • It’s use resulted in teeth accumulating dark stain.

Fluoride compounds • Sodium monofluorophosphate (MFP): • Most popular fluoride component. • Compatible with most abrasives. • Some research suggests that its effect is by direct incorporation of MFP into the apatite crystals. • Other research suggests that enzymatic hydrolysis of MFP within dental plaque, is more important.

Fluoride compounds • Amine fluoride • Lab research demonstrated: • It was superior to more widely used inorganic compounds • Had a strong affinity for enamel • Had a direct anti-enzymatic effect on plaque bacteria. • combined with stannous fluoride, several studies reported an increased effect on dental plaque and enamel fluoride accumulation.

Evidence for effectiveness • More than 60 years of research demonstrated the benefits of fluoride toothpastes. • Studies are of relatively high quality, and provide clear evidence that fluoride toothpastes are effective in preventing caries. • The decline in the prevalence in dental caries in industrialized countries in the past 30 years can be attributed mainly to the widespread use of fluoride toothpastes.

Permanent teeth • Fluoridated toothpaste significantly reduces DMFS compared to non-fluoride toothpaste or no toothpaste at all (Prevented fraction= 24%). • The effect increased with higher baseline levels of DMFS, fluoride concentration, frequency of use, and supervised brushing. • Not influenced by exposure to water fluoridation. (Marinho et al., 2003A)

Primary teeth • 1,000–1,500 ppm fluoride toothpaste reduces dmfs in primary teeth compared to placebo or no intervention (Prevented Fraction 31%). • However, most studies were in a population where the prevalence of dental caries in pre-school children is high. (Santos et al., 2013)

Root Caries • Exposed dentine, usually in elders. • Requires toothpaste with low abrasivity. • Higher concentration toothpastes (5000 ppm F) significantly better at remineralizing primary root surface carious lesions (Baysen et al., 2001).

Optimum concentration • The maximum amount of fluoride allowed in toothpaste before it is classified as a medicine is 1500 ppm. • The benefits of increasing fluoride concentration start at 1000 ppm and above. • Concentrations of 550 ppm and below showed no statistically significant effect when compared to placebo. (Walsh et al., 2009)

Brushing frequency and technique • Reduction of caries increases with higher frequency of brushing, and brushing supervision (Marinho et al., 2003A). • Rinsing with water after brushing reduces the caries-preventive effect and should be discouraged (Sjogren et al., 1995; Chestnutt et al., 1998). • Brushing last thing at night leads to longer retention of fluoride in the saliva (Duckworth and Moore 2001)

Risk of fluorosis • Related to: 1. Age of child. 2. Fluoride concentration. 3. Amount of toothpaste. 4. Swallowing. 5. Supervision. 6. Fluoride supplements/water fluoridation.

Fluoride mouthwashes • First study on their use was in 1946. • Can be used at home or as part of a community preventive program. • Sodium fluoride is the compound of choice due to: • Superior effectiveness in caries reduction. • Ease of formulation of a pleasant-tasting rinse. • Amine-F with Stannous-F reported to be even more effective. • Other compounds not recommended.

Fluoride mouthwashes • Usually come in a concentration of 200-1000 ppm. • Two types: • Daily rinse 0.05% NaF (225 ppm) • Weekly rinse 0.2% NaF (900 ppm) • Rinsing time of 1-2 minutes. • Not suitable for younger children due to increased risk of ingestion.

Evidence for effectiveness • Supervised use of F-mouthrinses, regardless of F concentration and frequency, is associated with a reduction in caries increment in children (prevented DMFT fraction=25%). • No studies looked into impact on primary teeth. • Lack of research regarding adverse effect such as acute toxicity and fluorosis (Marinho et al., 2003B). (Marinho et al., 2003B)

Evidence for effectiveness • The caries-preventive effect of fluoride mouthrinses is not significantly different from fluoride toothpaste (Marinho et al., 2003C). • Evidence that daily sodium fluoride mouthwash reduces the severity of enamel decay surrounding a fixed brace (Benson et al., 2004)

Recommendations for the use of fluoride toothpaste and mouthwash

Sources • Public Health England (PHE) • Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) • American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) • European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (EAPD)

PHE Guidelines - toothbrushing • Toothpaste amount: • Smear for 6 months-3 years • Pea-sized for 4 years-6 years • Full-sized for 7+ years.

PHE Guidelines - toothbrushing • Frequency: x2 a day, including last thing at night. • Supervision: until the age of 7. • Spit out after brushing and do not rinse.

PHE Guidelines – F-Mouthwash • Should be used at a different time to toothbrushing to maximise the topical effect.