Public Choice and Public Goods

690 likes | 1.69k Vues

Public Choice and Public Goods. CHAPTER 16. © 2003 South-Western/Thomson Learning. Introduction. In most of our previous discussions, we have been talking about private goods Private goods have two important features

Public Choice and Public Goods

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Public Choice and Public Goods CHAPTER 16 © 2003 South-Western/Thomson Learning

Introduction • In most of our previous discussions, we have been talking about private goods • Private goods have two important features • They are rival in consumption the amount consumed by one person is unavailable for others to consume • They are exclusive suppliers can easily exclude those who don’t pay

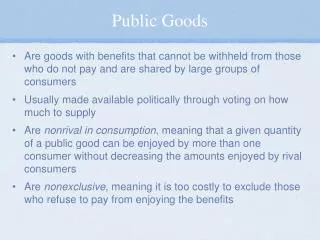

Public Goods • Public goods, such as national defense, the Center for Disease Control, or a neighborhood mosquito-control program are • Nonrival in consumption one person’s consumption does not diminish the amount available to others once produced, such goods are available to all in equal amount the marginal cost of providing the good to additional consumers is zero • Once a public good is produced, suppliers cannot easily deny it to those who fail to pay it is nonexclusive

Public Goods • Because they are nonrival and nonexclusive, for-profit firms cannot profitably sell public goods • In this case of market failure, government can improve the situation by providing public goods and paying for them through enforced taxation

Classification of Goods • An economy consists of more than just private and public goods • Some goods are nonrival but exclusive • For example, additional households can watch a TV show without affecting the TV reception of other viewers

Classification of Goods • Along the same lines, short of the point of congestion, additional people can benefit from a golf course, swimming pools, and so on • These goods, when not congested, are non rival, yet producers can, with relative ease, exclude those who don’t pay the greens fees, pool admission, etc. • Once congestion sets in, these quasi-public goods become private goods

Classification of Goods • Some other goods are rival but nonexclusive • The fish in the ocean are rival in the sense that once caught they are not available for others to catch are rival • However, these goods are nonexclusive in the sense that it would be costly or impossible for a private firm to prevent access to these goods open-access goods • Exhibit 1 offers a matrix for all goods

Exhibit 1: Categories of Private and Public Goods Rival Nonrival Across the top, goods are either rival or nonrival. Down the left, goods are either exclusive or nonexclusive. 1.Private Goods 2.Quasi-Public Goods —pizza —Cable TV —crowded Exclusive swimming —uncrowded pool swimming pool Open-access goods are usually regulated by government, and public goods are usually provided by government. 3.Open-Access 4.Public Goods Goods —national defense —ocean fish Nonexclusive —mosquito control —migratory birds

Optimal Provision of Public Goods • Because private goods are rival in consumption, the market demand for a private good is the sum of the quantities demanded by each consumer horizontal sum of all individual demand curves • The efficient quantity of a private good occurs where the market demand curve intersects the market supply curve

Optimal Provision of Public Goods • But since a public good is nonrival in consumption, the good, once produced, is available to all consumers in an identical amount • Therefore, the market demand curve for a public good is the vertical sum of each consumer’s demand for the public good • To arrive at the efficient level of the public good, we find where the market demand curve intersects the marginal cost curve

Optimal Provision of Public Goods • Suppose the public good in question is mosquito control in a neighborhood, which, or simplicity, consists of only two houses • One is headed by Alan and the other by Maria • Alan spends a lot of time in the yard, thus values a mosquito-free environment more than does Maria • Exhibit 2 shows their demand curves

e Marginal cost $15 10 Dm 5 2 Exhibit 2: Market for Public Goods D Da and Dm are the respective demand curves reflecting the marginal benefits that Alan and Maria, respectively, enjoy at each rate of output. Da How much mosquito spraying should the government provide? Suppose the marginal cost of spraying is a constant $15 an hour. The efficient level of output is found where the marginal benefit to the neighborhood equals the marginal cost 2 hours per week. Dollars per hour D 0 Hours of mosquito spraying per week

Optimal Provision of Public Goods • The government pays for the mosquito spray through taxes, user fees, or some combination of the two • The efficient approach would be to impose a tax on each resident equal to his or her marginal valuation. There are, however, two problems with this • Once people realize their taxes are based on how much the government thinks they value the good, people tend to understate their true valuation

Optimal Provision of Public Goods Why admit you really value the good if, as a result, you get a higher tax bill? • Taxpayers are reluctant to offer this information, creating what is called the free-rider problem • The free-rider problem occurs because people try to benefit from a public good without paying for it • For example, all will benefit from the mosquito abatement program, whether they pay or not Even if the government had accurate information about marginal valuations, some households earn much more than others a greater ability to pay taxes • Taxing people according to their marginal valuations may be efficient, but it may not be considered fair or equitable

Public Choice in Representative Democracy • Government decisions about the provision of public goods and the collection of tax revenues are public choices • In a democracy, public choices usually require approval by a majority of voters • We can frequently explain the choice of the electorate with majority rule by focusing on the preferences of the median voter

Median-Voter Model • The median voter is the one whose preferences lie in the middle of the set of all voters’ preferences • The median-voter model predicts that under certain circumstances, the preference of the median, or middle voter will dominate other choices • To see the logic of this, consider the following situation

Median-Voter Model • Suppose we have three individuals who are trying to decide whether to buy a TV and, if so, of what size • The problem is that each of the individuals have different preferences • Suppose we let N = no TV, S = small TV, and L = large TV, and p preferred • Person 1: N p S p L • Person 2: L p S p N • Person 3: S p L p N

Median-Voter Model • All agree to make the decision by voting on two alternatives at a time, then pairing the winner against the remaining alternative until one dominates the other • When the small set is paired against the no-TV option, the small set wins by getting the vote of individuals 2 and 3 • Then when the small set is paired against the large TV it also wins because individuals 1 and 3 approve

Median-Voter Model • Person 3, the median voter in this case, gets his most preferred choice • In fact, even if person 3 had preferred the large TV, he would have gotten his choice • This same principle often holds in public choices political candidates try to get elected by appealing to the median voter

Median-Voter Model • This is one reason why candidates often seem so much alike • Other voters are required to go along with what the median voter wants • Thus other voters usually end up paying for what they consider to be either too much or too little of the public good welfare cost of public goods

Public Choices • Rather than make decisions by direct referenda, voters elect representatives • In theory, these representatives make public choices that reflect their constituents’ views • Under certain conditions, the resulting public choices reflect the preferences of the median voter

Special Interest and Rational Ignorance • What do governments attempt to maximize? • There is no common agreement about what governments maximize or, more precisely, what elected officials maximize, if anything • One theory that parallels the rational self-interest assumption employed in private choices is that elected officials attempt to maximize their political support

Special Interest and Rational Ignorance • It is possible that elected representatives will cater to special interests rather than serve the interests of the majority • The problem arises because of the asymmetry between special interests and the public interest • Consider only one of the thousands of decisions that are made by elected representatives: funding wool production

Special Interest and Rational Ignorance • Under the wool-subsidy program, the federal government guarantees that a floor price to sheep farmers that costs taxpayers over $75 million per year • The only person the testify before Congress in support of this program was a representative of the National Wool Growers Association, who claimed that the subsidy was vital to the nation’s economic welfare • Why didn’t single taxpayer challenge the subsidy?

Special Interest and Rational Ignorance • Households consume so many different public and private goods and services that they have neither the time nor the incentive to understand the effects of public choices on every one of those products • What’s more, voters realize that each of them has only a tiny possibility of influencing the outcome of public choices

Special Interest and Rational Ignorance • Finally, even if an individual voter is somehow able to affect the outcome, the impact on that voter is likely to be small • For example, in the case of the wool subsidy, the average taxpayer would save less than 60 cents per year in federal income taxes

Special Interest and Rational Ignorance • Therefore, unless voters have a special interest in the legislation, they adopt a stance of rational ignorance • Rational ignorance that they remain largely oblivious to the costs and benefits of the thousands of proposals considered by elected officials • The cost to the typical voter of acquiring and acting on such information is usually greater than any expected benefits

Special Interest and Rational Ignorance • In contrast, consumers have more incentive to gather and act on information about decisions they make in private markets because they benefit directly from such information • Since information and the time required to acquire and digest it are scarce, consumers concentrate on private choices rather than public choices because the payoff in making wise private choices is usually more immediate, direct, and substantial

Distribution of Costs and Benefits • The possible combinations of benefits and costs yield four categories of distributions • Widespread benefits and widespread costs • Concentrated benefits and widespread costs • Widespread benefits and concentrated costs • Concentrated costs and concentrated benefits

Distribution of Costs and Benefits • Traditional public-goods legislation • Widespread benefits and widespread costs nearly everyone benefits and nearly everyone pays • Usually has a positive impact on the economy because total benefits exceed total costs • Special-interest legislation • Benefits are concentrated but costs widespread • Program’s costs are spread across nearly all consumers and taxpayers • Generally harms the economy, on net, because total costs often exceed total benefits

Distribution of Costs and Benefits • Populist legislation • Widespread benefits but concentrated costs • Usually has a tough time getting approved because the widespread group that benefits typically remains rationally ignorant of the proposed legislation voters provide little political support • The concentrated group adversely affected will object strenuously • Tort reform is one example that would benefit the economy as a whole by limiting product liability. • However trial lawyers, the group most harmed by such limits, have blocked passage

Distribution of Costs and Benefits • Competing-interest legislation • Involves both concentrated benefits and costs • Example: relative market position of Microsoft versus AOL • Exhibit 3 arrays the four categories of distributions

Exhibit 3: Categories of Legislation Distribution of Benefits Widespread Concentrated 1. Traditional Public Goods - National Defense 2. Special Interest - Farm Subsidies Widespread Distribution of Costs 3. Populist - Tort Reform 4. Competing Interest - Labor Union Issues Concentrated

Rent Seeking • An important feature of representative democracy is the incentive and political power it offers participants to employ legislation that increases their wealth • either through direct transfers or • through favorable public expenditures and regulations • Special-interest groups try to persuade elected officials to approve measures that provide special interest with some market advantage or outright transfer or subsidy

Rent Seeking • Such benefits are sometimes called rents • The term in this context means that the government transfer or subsidy constitutes a payment to the resource owner that exceeds the earnings necessary to call forth that resource payment exceeding opportunity cost • The activity that interest groups undertake to elicit these special favors from government is called rent-seeking

Rent Seeking • The government frequently bestows some special advantage on a producer group or group of producers, and abundant resources are expended to secure these rights • Political action committees, PACs, contribute millions to congressional campaigns

Rent Seeking • To the extent that special-interest groups engage in rent-seeking, they shift resources from productive endeavors that create output and income to activities that focus more on transferring income to the special interest • Resources employed to persuade government to redistribute income and wealth are unproductive because they do nothing to increase output and usually end up reducing it

Rent Seeking • Often firms compete for the same government advantage, thereby wasting still more resources • If the advantage conferred by government on some special-interest group requires higher income taxes, the net return individuals expect from working and investing will fall they may work and invest less

Rent Seeking • As a firm’s profitability becomes more and more dependent on decisions made in Washington, resources are diverted from productive activity to rent seeking, or lobbying efforts, to gain special advantage • Special-interest groups have little incentive to make the economy more efficient • In fact, they will usually support legislation that transfers wealth to them even if overall efficiency declines

Rent Seeking • Think of the economy’s output in a particular period as a pie where the pie represents the total value of goods and services produced • In answering the “what,” “how,” and “for whom” questions policy makers have three alternatives • They can introduce changes that increase the size of the pie positive sum game

Rent Seeking • They can decide simply to carve up the existing pie differently redistribute income • They can start fighting over the how the pie is carved up, causing some of it to end up on the floor negative sum game

Underground Economy • It is reasonably accurate to say that when government taxes productive activity, less production gets reported • The underground economy is a term used for all market activity that goes unreported to the government to either avoid taxes or because the activity itself is illegal

Underground Economy • The introduction of a tax on productive activity has two effects • First, resource owners may supply less of the taxed resource since the after-tax wage declines • Second, to evade taxes, some people will shift from the formal, reported economy to an underground, “off-the-books” economy

Underground Economy • Must distinguish between • Tax avoidance: a legal attempt to arrange one’s economic affairs so as to pay the least possible tax • Example: buying municipal bonds because they yield tax-free interest • Tax evasion : illegal • Takes the form of either failing to file a tax return or filing a fraudulent return by understating income or overstating deductions

Underground Economy • Research around the world indicates that the underground economy grows more when • Government regulations increase • The tax rate increases • Government corruption is more widespread • U.S. Commerce Department estimates that official figures capture only 90% of U.S. income while the Internal Revenue Service estimates only 87% of taxable income gets reported

Summary • Those who pursue rent-seeking activities and those involved in the underground economy view government from opposite sides • Rent seekers want government to become actively involved in transferring wealth to them • Those in the underground economy want to avoid government contact

Bureaucracy • Elected representatives approve legislation • However, the task of implementing that legislation is typically left to bureaus • Bureaus are government departments and agencies whose activities are financed by appropriations from legislative bodies

Ownership and Funding of Bureaus • Taxpayers are in a sense the “owners” of government bureaus in the jurisdiction in which they live • If the bureau earns a “profit,” taxes may decline; if it operates at a “loss,” as most do, this loss must be covered by taxes • Each taxpayer has just one vote, regardless of the taxes paid and ownership is not transferable

Ownership and Funding of Bureaus • Bureaus are typically financed by a budget appropriation from the legislature which comes from taxpayers • Becomes of the differences in the forms of ownership and in the sources of revenue, bureaus have different incentives than do for-profit firms they are likely to behave differently

Ownership and Behavior • A central assumption of economics is that people behave rationally and respond to economic incentives • The more closely compensation is linked to individual incentives, the more people will behave in accordance with those incentives • A private firm receives a steady stream of consumer feedback