Explanations

110 likes | 341 Vues

Explanations. Explanations can be thought of as answers to why-questions They aim at helping us to understand some range of data The exact nature of an explanation will differ based on its subject: mathematical, physical, psychological, etc. Inference to the Best Explanation.

Explanations

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Explanations • Explanations can be thought of as answers to why-questions • They aim at helping us to understand some range of data • The exact nature of an explanation will differ based on its subject: mathematical, physical, psychological, etc.

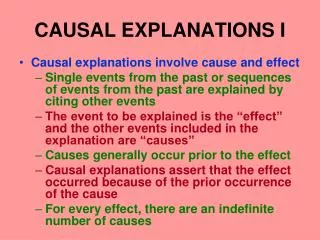

Inference to the Best Explanation • IBE arguments typically appeal to theories: sets of concepts, ideas, and hypotheses intended to offer an explanation. (Theories are NOT mere opinions or speculation.) • IBE arguments are based on the ideas of verisimilitude (approximate truth) and corroboration (provisional support). • The strategy of IBE arguments is to argue that some hypothesis or theory possesses verisimilitude because it is the best available explanation for some range of data. • IBE arguments are the primary form of reasoning used in the sciences

Evaluating Explanations • Explanations are typically evaluated in comparison to an alternative. The only time this is not the case is when one makes a case that the explanation offered is the only available explanation. Explanations are to be rejected only in light of a better alternative. • Alternatives are not always explicitly laid out—sometimes the competitor is assumed. • There is no single standard or feature used for judging competing explanations; rather, there are several “virtues” that can make an explanation superior to its competitors.

Simplicity • Occam’s Razor: do not multiply entities beyond necessity; i.e. do not appeal to unnecessary elements in offering explanations. • This can involve: (1) number of entities, (2) number of fundamental kinds of entities, (3) number of non-reducible properties, (4) number of non-reducible laws, and (5) computational simplicity • Why? These elements increase the likelihood that the explanation is in fact false. Failure story: Gremlins. • Success Story: Copernicus’ Heliocentric solar system

Explanatory Scope • Judgment regarding how much of the data is explained by the theory in question • Success Story #1: Psychoanalysis • Success Story #2: Evolution

Explanatory Depth • This is a judgment of the explanation’s ability to account for the specific details and mechanisms involved in the data • Failure Story #1: AIDS is God’s punishment • Failure Story #2: 9/11 happened because God “withdrew His [sic] hand of protection from the United States”

Unification • Good theories will tend to show how ranges of data originally thought distinct are really results of the same mechanisms • Success Story #1: Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation • Success Story #2: Evolution • Main concern is to avoid spurious unification—unification that lacks explanatory depth. (Failure story: Theological determinism)

Predictive Novelty • Good theories will tend to be predictively (and retrodictively) accurate. • More important still is predictive novelty—the ability to make predictions that competitor theories don’t, which turn out to be true. • Success Story: Relativity Theory • Predictive failures do not guarantee a bad theory—there may be many reasons why predictions fail (reliance on false background assumptions, poor experimental design, etc.). However, repeated predictive failures (esp. novel predictions) should lower our confidence in the adequacy of a theory.

Fecundity • Good explanations will tend to open up further avenues for research • Success/Failure Story: Evolution vs. “Scientific” Creationism • Success Story: Neuroscience • Failure Story?: Paul Churchland on “Folk Psychology”

Fit (or Coherence) • Coherence with what we already know; improves understanding by minimizing belief revision • Weak Fit if it is consistent with what we already have justification for believing; Strong Fit if it is implied by what we already have justification for believing • Narrow Fit if it coheres with what the individual is justified in believing; Wide Fit if it coheres with the justified belief of a community • Peripheral Fit if it coheres with less central beliefs; Central Fit if it coheres with foundational beliefs. • All of these are a matter of degree: the closer to Strong, Wide and Central Fit, the better.

Examples • Arthur Butz’ “Emigration” theory: the 6 million “missing” Jews from Europe were not actually killed, but rather were forcibly emigrated to other nations • Evolutionary Theory vs. “Scientific” Creationism (a.k.a. Intelligent Design Theory)