Chronic viral hepatitis

400 likes | 1.25k Vues

Chronic viral hepatitis. Chronic viral hepatitis. Approximately 90-95% of cases of acute hepatitis B in neonates, 5% of cases of acute hepatitis B in adults, and as many as 85% of cases of acute hepatitis C demonstrate histologic evolution into chronic hepatitis. . Hepatitis B.

Chronic viral hepatitis

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Chronic viral hepatitis Approximately 90-95% of cases of acute hepatitis B in neonates, 5% of cases of acute hepatitis B in adults, and as many as 85% of cases of acute hepatitis C demonstrate histologic evolution into chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis B • Epidimiology of hepatitis B virus • HBV is a member of the Hepadnaviridae family. • Infection with HBV is defined by the presence of HBsAg. Approximately 5% of the world's population (i.e., 300 million people) is chronically infected with HBV. Maintenance of a high HBsAg carriage rate in these parts of the world is partially explained by the high incidence of perinatal transmission and by the low rate of HBV clearance by neonates.

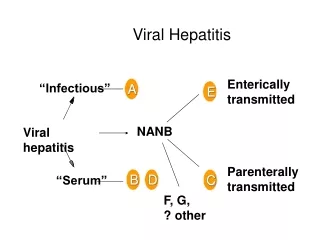

Fecal_oral Parenteral Sexual Perinatal Sporadic (unknown) HAV +++HEV +++ HBV +++HCV +++HDV ++HGV ++HAV + HBV +++ HDV ++ HCV + HBV +++ HCV + HDV + HBV + HCV + Mode of Transmission

Transmission of hepatitis B virus • HBV is readily detected in serum. It isseen at very low levels in semen, vaginal mucus, saliva, and tears. The virus is not detected in urine, stool, or sweat. HBV can survive storage at -20°C and heating at 60°C for 4 hours. It is inactivated by heating at 100°C for 10 minutes or by washing with sodium hypo chlorite (bleach).

Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus • The vast majority of HBV cases around the world are due to perinatal transmission. Infection appears to be due to contact with a mother's infected blood at the time of delivery, as opposed to transplacental passage of the virus. Perinatal infection usually is asymptomatic. Although breast milk can contain HBV virions, the role of breastfeeding in transmissionis unclear

HBV is transmitted more easily than HIV or HCV.. However, HBV cannot be transmitted through kissing, or household contact such as sharing towels, eating utensils, or food. Sexual activity is estimated to account for as many as 50% of HBV cases in the United States

Patients with hemophilia, those on renal dialysis, and those who have undergone organ transplants remain at increased risk of infection. Intravenous drug use accounts for 20% of US cases of HBV. The prevalence of HBV in those who use intravenous drugs is approximately 50%. The risk of acquiring HBV after a needle stick from an infected patient is estimated to be as high as 5%.

Natural history of hepatitis B virus • The incubation period of HBV is 40-150 days, with an average of approximately 12 weeks. As with HAV, the clinical illness associated with acute HBV infection may range from mild disease to a disease as severe as FHF (seen in <1% of patients

After acute hepatitis resolves, 95% of adult patients and 5-10% of infected infants ultimately develop anti-HBV antibody, clear HBsAg (and HBV virions), and fully recover. Five percent of adult patients and 90-95% of infected infants develop chronic infection

With the development of chronic infection (as marked by a positive HBsAg finding), 70-90% of HBsAg carriers enter the healthy-carrier state. They have no symptoms, normal liver chemistry test results, negative findings for markers of active viral replication, and normal or minimally abnormal liver biopsy results. They remain infectious to others through parenteral or sexual transmission.

Healthy carriers ultimately may develop HBsAb and clear the virus. However, some healthy carriers develop chronic hepatitis, as determined by biopsy. Healthy carriers remain at risk for the development of HCC. The author's practice is to screen healthy carriers every 6 months with ultrasound and alpha-fetoprotein testing to help rule out the interval development of HCC. However, this point is controversial

Of HBsAg carriers, 10-30% develop chronic hepatitis. These patients often are symptomatic. They have abnormal aminotransferase levels, a positive finding of HBeAg or HBV DNA, and abnormal liver biopsy findings. They are highly infectious to others through parenteral or sexual transmission. They also are at significant risk for progression to cirrhosis or HCC. Patients with chronic hepatitis B also should undergo screening to help rule out HCC

Fatigue is the most common symptom of chronic HBV infection. Patients occasionally may experience an acute flare of their disease, with symptoms and signs similar to that of acute hepatitis. Patients also may have extrahepatic manifestations of their disease, including polyarteritis nodosa, cryoglobulinemia, and glomerulonephritis.

Diagnosis of acute self-limited hepatitis B virus infection • HBsAg is the first serum marker seen in those with acute infection. It represents the presence of HBV virions (Dane particles) in the blood. HBeAg, a marker of viral replication, also is present. When viral replication slows, HBeAg disappears and anti-HBe is detected. Anti-HBe may persist for years. • The first antibody to appear is anti-HBc (HBcAb). Initially, it is of the IgM class. Indeed, the presence of IgM anti-HBc is diagnostic for acute HBV infection

Weeks later, IgM anti-HBc disappears and IgG anti-HBc is detected. Anti-HBc may be present for life. The presence of anti-HBc demonstrates that the patient has had a history of infection with HBV at some point in the past. • In patients who clear the HBV, HBsAg usually disappears 4-6 months after infection, as titers of anti-HBs (HBsAb) become detectable. Anti-HBs is believed to be a neutralizing antibody, offering immunity to repeated exposures to HBV. Anti-HBs may persist for the life of the patient

Knowing key points helps in the interpretation of serology findings in acute HBV infection. The presence of HBsAg does not indicate whether the infection is acute or chronic. The presence of IgM anti-HBc is the sine qua non of acute HBV infection. The presence of IgG anti-HBc indicates that a patient has been infected with HBV at some point. It remains positive both in patients who clear the virus and in patients with persistent infection.

The presence of IgG anti-HBc with a negative HBsAg and a negative anti-HBs indicates 1 of 4 things. First, the test result is a false positive. Second, the patient is in a "window period" of acute hepatitis, between the elimination of HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs. This scenario is not seen in patients with chronic HBV infection. Third, the patient has cleared the HBV virus but has lost anti-HBs over the years. Fourth, the patient is one of the uncommon individuals with active HBV replication who is negative for HBsAg. This situation is diagnosed when either a positive HBeAg or a positive HBV DNA result is found.

Diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B virus infection • HBsAg may remain detectable for life in many patients. Individuals who have positive findings for HBsAg are termed carriers of HBV; they may be healthy carriers or they may have chronic hepatitis. Anti-HBc is present in all patients with chronic HBV infections. HBeAg and HBV DNA may or may not be present. If present, they reflect a state of active viral replication and a high level of infectivity. Anti-HBs usually are absent in patients with chronic infection. If anti-HBs are present in a patient who has positive HBsAg findings, it reflects the presence of a low level of antibody that was unsuccessful at inducing viral clearance

Markers after vaccination for hepatitis B virus • The HBV vaccine delivers recombinant HBsAg to the patient, without HBV DNA or other HBV-associated proteins. More than 90% of recipients develop protective anti-HBs. Vaccine recipients are not positive for anti-HBc unless they previously were infected with HBV

Treatment of chronic hepatitis B • Interferons have both antiviral and immunomodulatory effects. Treatment with alfa-interferon is appropriate for many patients with chronic hepatitis B. Candidates for interferon therapy must have a clinical diagnosis of chronic HBV infection, with an elevated level of alanine aminotransferase (ALT). They must have evidence of active HBV replication, as marked by a positive HBeAg or a positive HBV DNA finding. The author recommends that liver biopsy be performed prior to therapy to confirm the diagnosis and document the severity of disease.

Interferon is less effective in those with lifelong HBV infection, those with a low ALT level (ie, <100 U/L), those with a high level of HBV DNA (ie, >100 pg/mL), those with end-stage renal disease, those with HIV infection, and those with immunosuppression (eg, following solid organ transplantation). • lamivudine: • . It inhibits DNA polymerase–associated reverse transcriptase and can suppress HBV replication. Treatment with a dose of 100 mg orally once per day for 1 year results in loss of HBeAg in 32% of patients.

vaccination • Plasma-derived and recombinant HBV vaccines use HBsAg to stimulate production of anti-HBs. The vaccines are highly effective, with a greater than 95% rate of seroconversion. Vaccine administration is recommended for all infants and for adults at high risk of infection (eg, those on dialysis, health care workers). • The recommended vaccination schedule for infants is an initial vaccination at the time of birth (ie, before hospital discharge), repeat vaccination at 1-2 months, and another repeat vaccination at 6-18 months.

Postexposure prophylaxis • Hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) is derived from plasma. It provides passive immunization for individuals who describe recent exposure to a patient infected with HBV. Recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis are included in Table 2. HBIG also is administered following liver transplantation to those infected with HBV, in order to prevent HBV-induced damage to the liver allograft.

Table 2. Post exposure Prophylaxis for Contacts of Patients Positive for HBsAg • Perinatal • HBIG + vaccination at time of birth (90% effective) • Sexual contact with an acutely infected patient • HBIG +/- vaccination • Sexual contact with a chronic carrier • Vaccination • Household contact with an acutely infected patient • None • Household contact with an acutely infected person resulting in known exposure • HBIG +/- vaccination • Infant (<12 mo) primarily cared for by an acutely infected patient • HBIG +/- vaccination • Inadvertent percutaneous or permucosal exposure • HBIG +/- vaccination

Hepatitis C • HCV is a Flavivirus. It is a 9.4-kb RNA virus, with a diameter of 55 nm. It has 1 serotype and multiple genotypes. Profound genetic variability exists among HCVs throughout the world. At least 6 major genotypes and more than 80 subtypes are described • Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus • Hepatitis C is prevalent in 0.5-2% of populations

Transmission of hepatitis C virus via intravenous and intranasal drug use • Intravenous drug use remains an important mode of transmitting HCV. Intravenous drug use and the sharing of paraphernalia used in the intranasal snorting of cocaine and heroin account for approximately 60% of new cases of HCV infection. More than 90% of patients with a history of intravenous drug use have been exposed to HCV. • Transmission of hepatitis C virus via occupational exposure • Occupational exposure to HCV accounts for approximately 4% of new infections. On average, the chance of acquiring HCV after a needle stick injury involving an infected patient is 1.8% (range, 0-7%). Importantly

Transmission of hepatitis C virus via sexual contact Approximately 20% of cases of hepatitis C appear to be due to sexual contact. • Transmission of hepatitis C virus via perinatal transmission Perinatal transmission appears to be uncommon. It is observed in fewer than 5% of children born to mothers infected with HCV. The risk of perinatal transmission of HCV is higher, estimated at 18%, in children born to mothers co-infected with HIV and HCV. Available data show no increase in HCV infection in babies who are breastfed. The US Public Health Service does not advise against pregnancy or breastfeeding for women infected with HCV.

Natural history of chronic hepatitis C • Only approximately 15% of patients acutely infected with HCV lose virologic markers for HCV. Thus, approximately 85% of newly infected patients remain viremic and may develop chronic liver disease. In chronic hepatitis, patients may or may not be symptomatic, with fatigue being the predominant complaint. Aminotransferase levels may fluctuate from the reference range (<40 U/L) to 300 U/L. However, no clear-cut association exists between aminotransferase levels and symptoms or risk of disease progression.

Natural history of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C • Patients with chronic hepatitis C are at risk for extrahepatic complications. In essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, HCV may form immune complexes with anti-HCV (IgG) and with rheumatoid factor. The deposition of immune complexes may cause small-vessel damage. Complications of cryoglobulinemia include rash, vasculitis, and glomerulonephritis. Other extrahepatic complications of HCV infection include focal lymphocytic sialadenitis, autoimmune thyroiditis, porphyria cutanea tarda, lichen planus, and Mooren corneal ulcer

Pathologic findings of hepatitis C • Lymphocytic infiltrates, either contained within the portal tract or expanding out of the portal tract into the liver lobule (interface hepatitis), commonly are observed in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Portal and per portal fibrosis may be present. Other classic histological features of the disease include bile duct damage, lymphoid follicles or aggregates, and macrovesicular steatosis

Diagnosis of hepatitis C • The most common tests used in the diagnosis of hepatitis C include liver chemistries, serologic tests, HCV RNA tests, and liver biopsies. • Diagnosis of hepatitis C using liver chemistries • Elevations of the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and ALT merely indicate the presence of liver injury. Patients with chronically elevated aminotransferase values should undergo a workup to exclude the possibility of chronic liver disease.

Indeed, patients can have HCV-induced cirrhosis and have normal liver chemistry values. Rises and falls in aminotransferase levels do not appear to correlate with clinical changes. However, normalization of AST and ALT levels following acute infection may signal clearance of HCV. Normalization of AST and ALT levels while a patient is undergoing treatment with interferon predicts a virologic response to treatment. Similarly, a rise in AST and ALT values may signal a relapse after apparently successful drug therapy. Anti-HCV test results remain negative for several months following acute HCV infection. After its appearance, • the anti-HCV usually remains present for the life of the patient. This occurs even in the 15% of cases in which the patient clears the virus and does not develop chronic hepatitis. Anti-HCV is not a protective antibody and does not guard against future exposures to HCV.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays and branched DNA assays have been used since the early 1990s to detect HCV RNA in serum. In contrast to ELISA, HCV RNA testing can confirm the presence of active HCV infection. • nosis of hepatitis C using liver biopsy • Liver biopsy is an important diagnostic test in suspected cases of chronic hepatitis C

Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection • Antiviral therapy has a number of major goals. These include (1) to decrease viral replication or eradicate HCV, (2) to prevent progression of disease, (3) to decrease the incidence of cirrhosis, (4) to decrease the incidence of HCC, (5) to ameliorate symptoms such as fatigue and joint pain, and (6) to treat extrahepatic complications of HCV infection such as cryoglobulinemia or glomerulonephritis.

Pegylated_interferon • The best success,according to published data is derived when IFN IS COMBINED with ribovirin • 49-54% had reversal of cirrhosis.