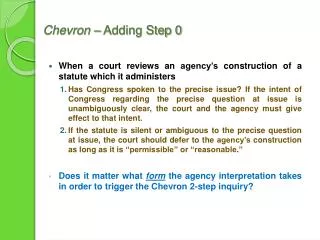

Chevron – Adding Step 0

150 likes | 1.8k Vues

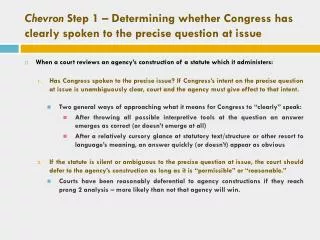

Chevron – Adding Step 0. When a court reviews an agency’s construction of a statute which it administers Has Congress spoken to the precise issue? If the intent of Congress regarding the precise question at issue is unambiguously clear, the court and the agency must give effect to that intent.

Chevron – Adding Step 0

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Chevron – Adding Step 0 • When a court reviews an agency’s construction of a statute which it administers • Has Congress spoken to the precise issue? If the intent of Congress regarding the precise question at issue is unambiguously clear, the court and the agency must give effect to that intent. • If the statute is silent or ambiguous to the precise question at issue, the court should defer to the agency’s construction as long as it is “permissible” or “reasonable.” • Does it matter what form the agency interpretation takes in order to trigger the Chevron 2-step inquiry?

Christensen v. Harris Co. (2000) – p. 187 • If the agency’s interpretation comes in the form of “force of law” interpretations (rulemaking or binding adjudications), courts should use traditional Chevron 2-step approach • BUT when the interpretation comes in the form of “shadow” law (e.g., policy manual, opinion letter, guidance documents) courts should not use traditional 2-step Chevron analysis • Rather such interpretations are “entitled to respect” but only to the extent that they have the “power to persuade” • Revival of Skidmore deference • Why should it matter whether an interpretation has the “force of law” or is a “shadow” law method of interpretation?

U.S v. Mead – the facts • U.S. Customs Service issued tariff classification ruling regarding the status of “day planners.” This classification represented a change in prior practice and resulted in an increase in taxable status. • These classifications were interpretations of federal statutory law giving the Sec’y of Treasury the power to “fix the final classification and rate of duty applicable to [certain] merchandise.” • Tariff classification letters, however, were not the product of “notice & comment” rulemaking; nor were they the result of binding adjudications although the Customs Service clearly had been delegated those powers. • Lower court withheld Chevron deference because the ruling letters were not preceded by notice-and-comment rulemaking, "do not carry the force of law" and "are not, like regulations, intended to clarify the rights and obligations of importers beyond the specific case under review." • If this case clearly involved “shadow law” per Christiansen, why did SCT grant cert?

Mead’s tweak of Christensen • Issue: Should court give Chevron deference to “shadow law” such as tariff rulings? • Mead majority: • “Administrative implementation of a particular statutory provision qualifies for Chevron deference when it appears that Congress delegated authority to the agency generally to make rules carrying the force of law, and that the agency interpretation claiming deference was promulgated in the exercise of that authority. Delegation of such authority may be shown in a variety of ways, as by an agency’s power to engage in adjudication or notice & comment rulemaking, or by some other comparable indication of congressional intent.”

Mead – majority’s reasoning vs. Scalia dissent • Nothing in the statute conveyed a congressional intent to authorize Customs to issue ruling letters with the force of law. • Statute’s reference to "binding rulings,“ did not "bespeak the legislative type of activity that naturally binds more than the parties to the ruling.” • Ruling letters might be precedential, but “precedential value alone does not add up to Chevron entitlement.” • Ruling letters are not clearly precedential because they are subject to independent review by the Court of Int’l Trade. • Customs never “set out with a lawmaking pretense in mind when it undertook to make classifications like these.” • “Customs has regarded a classification [letter] as conclusive only between itself and the importer to whom it was issued." • The letters come from 46 different Customs offices at a rate of 10,000-15,000 per year • What are Scalia’s objections to the Mead majority? Are they convincing?

Chevron vs. Mead/Skidmore deference • Chevron • Court gives deference to agency based on its status as an entity who has impliedly been delegated interpretive authority and which has exercised that authority through its delegated means (i.e., rule/order) • Deference so long as interpretation is “reasonable/permissible” – agency usually wins but must provide an explanation of sorts • Mead/Skidmore • Court defers to agency interpretation made through informal means because court thinks the interpretation is pretty good evidence the agency is right • Skidmore factors – is agency interpretation persuasive? • Is area w/in agency’s expertise? • Is interpretation contemporaneous w/ statute’s enactment? • Is interpretation longstanding or consistent? • Is interpretation supported by reasoned analysis? • What care did agency give to interpretation?

Gonzales v. Oregon – the statutes, etc. • Oregon DWDA – procedures where terminally ill patients can request meds from doctors to end lives. But meds are regulated by federal law. • Cont. Sub. Act (21 U.S.C. §829(a)):Controlled substances (meds) only available by prescription (Schedule II). • 21 CFR §1306.04: prescriptions must be issued “for a legitimate medical purpose by an individual practitioner acting in the usual course of his professional practice” • 21 U.S.C. §821: AG may issue rules re “registration” & “control” of controlled substances • 21 U.S.C. §822(a)(2) & 824(a)(4): Drs must register to issue lawful prescriptions. AG may deny/suspend doctor’s registration to dispense Schedule II drugs if “inconsistent with the public interest.” • 5 factors to consider re whether registration is in “public interest” • AG’s interpretative rule (66 Fed. Reg. 56608 (2001)):assisting suicide is not a legitimate medical purpose within the meaning of 21 § CFR 1306.04 and may render dr’s registration inconsistent w/ public interest under 21 USC §824(a)(4)

Gonzales v. Oregon - Seminole Rock/Auer deference • A.G. claims court should defer to interpretive rule (66 Fed. Reg. 56608) because it is interpreting his own regulation (21 CFR §1306.04) • Seminole Rock/Auer deference: court should defer to agency interpretation of its own ambiguous regulations unless it is clearly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation. • Why would a court give such deference to agency interpretations of their own regulations?

Gonzales v. Oregon – majority’s application of Seminole Rock/Auer deference • Why doesn’t the majority apply Auer deference here? • “[T]he existence of a parroting regulation does not change the fact that the question here is not the meaning of the regulation but the meaning of the statute. An agency does not acquire special authority to interpret its own words when, instead of using its expertise and experience to formulate a regulation, it has elected merely to paraphrase the statutory language.” • What is the majority worried about if it doesn’t distinguish between parroting and non-parroting regulations? • Problems with the majority’s approach?

Gonzales & Chevron Step 0 • A.G.’s interpretive rule can’t automatically get Chevron deference because it doesn’t fall into a “safe harbor” interpretive form – it’s an interpretive rule (not a binding rule or adjudication). • But it could still gain Chevron deference if Congress intended rule to have the binding force of law (Mead). • How did the majority answer this question? Why? • How did Justice Scalia? • What concerns push each opinion? What approach do they take? Who has the better answer?

Chevron’s Bottom Line • Chevron is known as a deferential standard because it requires courts to defer to “reasonable” agency interpretations of statutes that they administer • That deference at step 2 of Chevron, however, has caused fights to erupt at the other steps: • Step 0 – is Chevron deference inapplicable because the agency’s interpretation takes a form that does not deserve automatic deference? • Step 1 – is the statute really ambiguous or does it clearly mandate that the agency act a certain way? • Bottom line – if Chevron applies, it is deferential but whether it applies is not automatic