Timeline of Surgery

500 likes | 1.18k Vues

Timeline of Surgery . December 22, 2010. Minoans practice trephination c. 2500. This skull, excavated at Jericho in 1958 (tomb 88), shows 4 trephination holes at different stages of healing. One hole is almost completely healed. . Galen learns surgery by repairing gladiators' wounds - c. 157.

Timeline of Surgery

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Timeline of Surgery December 22, 2010

Minoans practicetrephinationc. 2500 • This skull, excavated at Jericho in 1958 (tomb 88), shows 4 trephination holes at different stages of healing. One hole is almost completely healed.

Galen learns surgery by repairing gladiators' wounds - c.157 • In CE 157, the Greek physician, Galen (CE 129-c. 200/216), was appointed doctor to the gladiators owned by the High Priest of Pergamum, his native city. He gained much valuable experience of the damage inflicted by wounds. Intestines often rolled out of stabbed abdomens and were replaced as quickly as possible, although survival was rare if the bowels themselves were penetrated. • Galen claimed an almost total success in his post as doctor to the gladiators since there were only 2 deaths under 5 High Priests compared with his predecessor's 60, none the result of wounds received in the arena.

Galen learns surgery by repairing gladiators' wounds - c.157 • Galen successfully sewed back an omentum (layer of peritoneal tissue) into the abdominal cavity, and removed a diseased breastbone from the slave of a comic playwright. Galen wrote about surgery in his book, Methodus Medendi. He closed wounds with bandages, sutures or the fibula, and ligated blood vessels with yarn or silk. He advocated dissection and vivisection (his were on animals) in order to learn how the body worked and avoid mistakes in surgery. • Galen claimed an almost total success in his post as doctor to the gladiators since there were only 2 deaths under 5 High Priests compared with his predecessor's 60, none the result of wounds received in the arena.

Surgical instruments • Roman armies had their own cutlers, armourers, and blacksmiths who were trained to produce surgical instruments as needed. Nevertheless, the complexity of some precision instruments suggests that the makers may have devoted themselves largely or wholly to this activity. Instrument makers produced needles, hooks, arrow extractors, scalpels, probes, scoops, catheters, dilators, bone chisels, cauteries, and forceps. • Most were made of copper, bronze or brass, a few from iron. Iron was used for scalpel blades while the handles were bronze. Blunt blades could be removed and replaced by a cutler, instrument maker or blacksmith. Roman blacksmiths understood the process of adding carbon to iron to produce steel although, according to Galen, the best quality surgical steel came from natural ores in northern Europe.

The Christian world divides • In CE 312, the Roman emperor, Constantine (d. CE 337), was converted to Christianity and the following year this was recognised as the official religion of the Roman Empire. His capital, Constantinople (formerly Byzantium), became the centre of the eastern Church although the bishop of Rome remained the most important figure in the West. Nevertheless, the two halves of the Empire gradually drew apart.

The Christian world divides • In the East, surgery was performed in some of the first Christian hospitals such as St Sampson's in Constantinople which had surgical patients by CE 650. In the West, Greek texts of Hippocrates and Galen were translated into Latin and studied in the monasteries of Europe. However, apart from brief tracts on phlebotomy (blood-letting) and cautery, there is little mention of surgery in the western medical literature of the 6th-11th centuries.

Arab-Islamic surgery • Medicine practised in the Arab-Islamic world derived from long-standing practices and also incorporated that of Greece and Rome. Many Greek texts were translated into Arabic. Arabic authors played an important role in preserving and adding to classical teaching. Those writing on surgery included the Persian physicians, Rhazes (d. 925), Haly Abbas (930-994), and Avicenna (980-1037). • Avicenna's Canon of medicine was enormously influential in the West throughout the Middle Ages and provided a largely Galenic system of medicine.

Arab-Islamic surgery • The Spanish physician, Albucasis (936-1013), wrote 30 surgical texts published in Latin translation as Liber Alzaharavii de Chirugia (12th century). The texts included operations for bladder stone and eye diseases, wound cauterisation, sutures, treatment of fractures and dislocations. There were, in addition, nearly 200 illustrations of surgical instruments, many of which he designed himself. • In Arab-Islamic medicine, the knife took second place to therapies such as pharmacy, bloodletting, and cupping.

Nevertheless, by the 13th century, there were new and improved surgical instruments such as scissors, trocars (used for piercing body cavities and withdrawing fluid), syringes, lithotrites (used to crush bladder stones), and sutures made from animal gut.

Cauterisation with a hot iron (cautery) was an important surgical technique. It was used to open abscesses and boils, arrest bleeding, burn skin tumours and haemorrhoids, treat epilepsy, stroke and melancholy. In patients who suffered recurrent dislocations, the cautery was used to produce scar tissue which permanently immobilised the joints.

The surgeons of southern Europe • In the western world, from the 12th-15th centuries, there was an increased output of surgical literature, both in Latin and the vernacular. The University of Salerno in southern Italy, founded in the mid-10th century, was an important centre for medical education which included theoretical (but not practical) surgery. • During the 13th century, the focus for medical studies moved to the universities of northern Italy at Bologna (founded 1113), Padua (1222), and Verona. • The first recorded public dissection of a human body (executed criminal) since the days of Herophilus (c. 330-260 BCE) and Erasistratus (c. 330-255 BCE) in Alexandria, took place at Bologna in about 1315. Dissection was acceptable to the church authorities provided that the body was of an executed criminal and that, following dissection, it was given a proper Christian burial.

Public dissection was spectacle, instruction, and edification all in one. It was sometimes staged in a church or municipal building, and usually in winter since cold slowed putrefaction. The abdominal cavity was the first to be exposed because it decayed the fastest. This was followed by the thorax (chest) and brain. Often, a robed physician sat on a dais reading from an anatomical text by Galen (although he never dissected humans), while a surgeon performed the dissection and a teaching assistant pointed out notable features.

Guy de Chauliac (1298-1368) was both physician (to the Pope in Avignon) and a surgeon. He was educated at Montpellier and Bologna. His Chirugia magna was translated many times and quoted in European surgical literature until the 18th century. These university-trained doctors, with their intellectual roots planted in the medical theory of ancient Greece, were almost certainly not typical of the surgeons operating in the everyday medieval world. Bruno Longoburgo, an Italian academic writer, considered that the practitioners in day-to-day contact with patients were 'for the most part ignorant and stupid peasants'. No doubt, there was a wide range of skills and intellect. In a male-dominated profession, there were at least 23 women surgeons licensed in the Kingdom of Naples between 1273-1410, 11 of whom had no restrictions on the sex of their patients.

By the end of the 15th century, there were growing numbers of practitioners who rejected scholastic theory in favour of an emphasis on learning through practice. One of these was the Italian surgeon, Leonardo di Bertipaglia (c. 1380-1465), who made an important contribution to surgical technique by introducing the suture-ligature to tie off bleeding blood vessels. He thus spared many patients the red-hot cautery or burning oil.

Itinerant practitioners and barber-surgeons • From the Renaissance to the 18th century, surgery and medicine were practiced in most of western Europe by separate groups of practitioners. However, surgery was rarely included in the university curriculum outside Italy. From the 12th century, physicians were licensed by universities. Surgeons were regulated by trade guilds and their closest occupational links were with barbers. Guilds of barber-surgeons were established in Europe from the 13th century.

The barber-surgeon was an artisan who practised both trades. Hair-cutting and shaving provided a regular day-to-day income and he trained through an apprenticeship. More often than not, he was illiterate. In France, by the mid-14th century, the physicians, surgeons, and barber-surgeons were organised into separate companies and had clearly defined roles. Dissections were under the direction of a physician but the knife-work was performed by a surgeon. In smaller towns, there was a more amicable association between the groups.

In this German miniature, a woman is seated on a bench, holding a bowl into which her blood spurts from an incision at the elbow. She is probably rhythmically squeezing a wooden stick in order to hasten the flow of blood. The surgeon, wearing a typical surgeon's hat of the period, holds her round the shoulder with his left hand whilst checking her pulse with his right. If the pulse weakened, bleeding was stopped. The elderly man at left is either washing his arm before blood-letting or holding it in warm water to enhance the blood flow.

Eye surgery and couching for cataract • Although most university educated doctors dissociated themselves from the bloody craft of surgery, an exception was made for eye operations. Eye surgery, being relatively bloodless, was performed by university graduates as well as itinerants. The Hebrew physician, Benvenutus Grassus (c. 1150), was educated at Salerno but settled in Montpellier after acquiring a wide reputation as a skilful operator on cataracts. The Greek term hypochysis, used to describe the cloudy film seen through the pupil, was translated by the Arabs as 'flowing down of water'. This was translated into Latin as 'cataract' by the Carthaginian monk, Constantine the African (c. 1020-1087). Cataract was believed to be the result of coagulated humours within the eyeball falling down in front of the lens.

Grassus used a gold or silver needle to dislodge the humour since these metals were soft and less likely to damage the eye than iron or steel. His technique was to push the humour well down in front of the pupil and hold it there until he had said 'four pater nosters'.

The Book of Tobit in The Apocrypha describes how Tobit, a Hebrew exiled in Ninevah (Mesopotamia), became gradually blind with a whiteness' in his eyes which he attributed to sparrow droppings while he slept by his courtyard wall. Local doctors were unable to help. Meanwhile, he sent his son, Tobias, on a journey to Rhages (now Rai, near Tehran) to redeem a fortune in silver from a cousin. During the journey, Tobias caught a large fish in the River

Tigris, and was advised to preserve the heart, liver and gall against evil spirits. When he eventually returned home, Tobias threw the fish gall into his father's eyes with the words, Be of good hope, my father'. The severe smarting caused Tobit to rub his eyes during which the whiteness' peeled away and he could see. The vigorous rubbing rather than the fish gall may have loosened Tobit's opaque lens from its supporting tissues, a not uncommon occurrence in mature cataracts. An early 20th century version of fish gall was sugar, described in the memoirs of a Jewish immigrant from Russia whose mother blew it into the eyes of his grandmother. She was never again troubled with cataract'.

The surgeon defined • In England, surgery was a Craft Guild until 1540 when the small Fellowship of Surgeons in London was united with the Barber-Surgeons' Company by Act of Parliament. The first master of the Company was Thomas Vicary (c. 1490-1561), surgeon to Henry VIII (reigned 1509-1547). • Henry granted the Company the annual right to dissect the bodies of 4 hanged criminals. This was increased to 6 by Charles II (reigned 1660-1685). • Barber-surgeons considerably outnumbered physicians and had an important role in what would now be regarded as primary care or general practice. They were less expensive to consult than physicians and, therefore, used by a wider section of the population. They set fractures, treated cuts and burns, knife wounds, tumours and swellings, ulcers and skin complaints. They also removed foetuses which had died in the womb, amputated limbs, and dealt with congenital defects such as tongue-tie and imperforate anus.

As well as being first master of the Company of Surgeons, Vicary was also appointed governor of St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, in 1548 and a ward was named after him. His code of practice for surgeons included keeping their patients' secrets, helping the poor as well as rich, not coveting any woman in a patient's house, not being a drunkard or so desirous of money to take in hande those cures that be uncurable...' However, he required patients to obey his orders however unpleasant, for he can not be called a pacient, unlesse he be a sufferer'.

Venereal diseases were officially the province of the surgeon. Syphilis, possibly carried from the Americas by Christopher Colombus's (1451-1506) sailors, raged through 16th century Europe. Surgeons also had the monopoly of embalming the dead. Some surgeons were licensed by the Barber-Surgeons' Company only for certain procedures such as bone-setting whilst others had wider practice rights. Surgeons who operated outside of their licence were punished as were those who failed to consult senior surgeons of the Company when faced with a difficult case. In 1605, Pascall Lane, was fined 40 shillings and sent to prison following the death of a child which he had 'ignorantly' and 'negligently' cut for bladder stone. Surgeons were not supposed to prescribe internal remedies, officially the province of the physician.

The reduction of fractures and dislocations were a case in point. In his surgical textbook, the Dutch surgeon, Paul Barbette (d. before 1675), did not trouble to describe the technique since it is better learnt by the frequent view of Practice than by Reading'.

Surgery and anatomy • In the Italian universities of the early 16th century, surgery and anatomy were often taught together. Anatomical dissection was sanctioned by ecclesiastical and civil authorities because the corpses were criminals who were both executed and anatomised in public. Anatomy was given a fillip in 1531 when *Galen's On anatomical procedures was translated into Latin as part of a general revival in the medicine of ancient Greece. The book set out the order in which a dissection should be carried out. By the early 1540s, an increasing number of anatomical works were being published, but the most important was De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body), by the Belgian anatomist, Andreas *Vesalius (1514-1564). Vesalius had been a dissector since his student days in Paris during the 1530s, robbing wayside gibbets and cemeteries for material.

Surgery and anatomy • In 1537, Vesalius was appointed lecturer in surgery and anatomy at Padua, an appointment which raised the status of both disciplines since he was a university educated physician. Numerous students went to Padua to learn anatomy, and for those who could not get there, Vesalius' book, De humani corporis fabricus, was a path-breaking account of human anatomy. As such, it contradicted Galen since he had only dissected animals. Vesalius believed that physicians should use their hands although many anatomical dissections continued to be made by 'demonstrators' while the students watched. After Vesalius, anatomy was progressively incorporated into university medicine. From 1546, the English physician, John Caius (1510-1573), who had shared lodgings for a time with Vesalius, gave anatomy lectures in English both to the College of Physicians in London and apprentices of the London Barber-Surgeons Company.

Vesalius' figures are shown, not in the aspect of death but as animated manikins against a backdrop of Italian countryside. • The fact that Vesalius' illustrations were widely and unashamedly plagiarised is ample proof that they were recognised as being far in advance of anything published up to that time. Nevertheless, later anatomists corrected Vesalius as he had corrected Galen.

Anatomists often had a hard time convincing people (including doctors) that dissection was a worthwhile procedure. Some, like the Italian artist, Michelangelo (1475-1564), were physically repulsed by the business of disembowelling; others believed that merely touching a dead body would pollute the living. Both Catholic and Protestant anatomists argued that contemplation of the body could lead to a knowledge of God's handiwork and hence of his nature and existence. The creation of university anatomy theatres helped establish dissection as a progressive subject. In the wake of Vesalius, young anatomists sought to establish priority in discovering new bodily structures.

Military and naval surgeons • Many surgeons drew on experience in military and naval surgery. After the introduction of gunpowder into warfare during the 15th century, the number and variety of injuries increased substantially. Practising military surgeons wrote some of the first surgical handbooks in the vernacular. The Buch der Wund-Artzney (Book of wound dressing, 1497) by Strasburg surgeon, Hieronymus Brunschwig (1450-1533), was the first printed book on surgery to appear in English translation (1525). It also contained the earliest printed illustrations of surgical instruments. Brunschwig endorsed the popular belief that gunshot wounds were poisoned by gunpowder and so required cauterisation, usually with a red-hot iron or boiling oil of elders mixed with theriac.

In this illustration from his Book of wound dressing, Hieronymus Brunschwig treats a man with a chest wound. He is accompanied by 2 assistants or relatives of the patient. Growing use of gunpowder-fired artillery often worsened the injuries confronting field surgeons because canonballs and lead shot destroyed more tissue than arrows or swords and left gaping wounds which were susceptible to putrefaction. A British surgeon, Alexander Read, wrote that Man in every age doth devise new instruments of death ... we have in our age, Gun-shot, the imitation of God his thunder; but the example is more fierce, and sendeth more souls to the devil, than the pattern'.

Ambroise Paré • The most celebrated barber-surgeon in western medicine was Ambroise Paré (1510-1590) of France, the son of a barber. He was appointed (c. 1533) aide-chirurgien at the Hôtel-Dieu, the only public hospital in Paris. In 1537, he became a military surgeon and for the next 30 years divided his time between following the French army and tending the sick in Paris. In Italy, on his first campaign (1537), he ran out of the boiling oil used to treat gunshot wounds and compromised with a salve of egg-white, rose-oil and turpentine. That night he slept badly, believing that the men whose wounds he had failed to burn would be dead by morning. In fact, they were in a much better state than those who had received the oil. Paré resolved never again to burn people who had been shot. In 1552, Paré entered the service of *Henri II but failed to save his life after he was wounded during a jousting tournament in 1559.

Paré (like the Roman author, Celsus) believed that the attributes of a surgeon were a strong, stable, and intrepid hand; a resolute and merciless mind; and an insensitivity to the 'common people' who spoke ill of surgeons because of their ignorance. • The most gruesome operation performed by Paré and his contemporaries was undoubtedly amputation of a limb. Surgeons were advised to take up their knives with a steddy hand and good speed'. It was no less a dreaded experience for the patient. Fabricius (c. 1533-1619), an Italian contemporary of Paré, told it how it was for many 16th century surgeons: I was about to cut off the thigh of a man of 40 years of age, and ready to use the saw, and Cauteries. For the sick man no sooner began to roare out, but all ranne away, except only my eldest Sonne, who was then but little, and to whom I had committed the holding of his thigh ... and but that my wife then great with child, came running out of the next chamber, and clapt hold of the Patient's Thorax, both he and myselfe had been in extreme danger'.

Surgeons and the law • In 13th century Spain and Italy, surgeons were called upon to give evidence as expert witnesses in suspicious or violent deaths. In cases of wounding, they were obliged to report to the authorities all cases of wounds which appeared to have been caused by violence or to certify if a wound would have, or had, caused death. In 1533, the Holy Roman Emperor, *Charles V (reigned 1519-1555) enacted a legal code (known as the Carolina) which stated that in all cases of suspected murder, surgeons had to be consulted. France passed a similar law (the edict of Valence) in 1536. The French barber-surgeon, Ambroise *Paré (1510-1590), produced a Treatise on reports (1575) in which he advised surgeons how to write legal reports on wounds, infanticide, death by lightning, and the signs of wounding, hanging, or suffocation. In England, surgeons appear not to have given evidence in murder trials until the 17th century.

Antisepsis and asepsis • Joseph Lister's (1827-1912) practice of 'antisepsis' whereby germs were destroyed or excluded from wounds through the application of antiseptic solutions, was gradually reconciled with 'asepsis'. This practice aimed to create an environment which was free from the presence of germs. Asepsis appealed to Victorian notions of cleanliness in both medical and moral matters. Cleanliness and hygiene were fundamental to the public health movement which aimed to sanitise environments and the people within them. Enthusiasm for asepsis led to improvements in hospital cleanliness, design, and ventilation, as well as the ritual of sterilising gowns, masks and gloves. In the late 1870s, the German bacteriologist, Robert *Koch (1843-1910) showed that Louis *Pasteur's (1822-1895) germ theory was essentially correct. He cultured and identified bacteria which caused specific infections.

Antisepsis and asepsis • In 1874, Pasteur suggested that surgical instruments could be sterilised in boiling water and then passed through a flame. This was an alternative to chemical antiseptics such as the carbolic used by Lister. Pasteur and Koch built the earliest steam sterilisers. • Pressure steam sterilisation was introduced by the Swiss surgeon, T Kocher (1841-1917), and his colleague, E Tavel (1858-1912), a bacteriologist. • During the 1880s, the German surgeons, Ernst von Bergmann (1836-1907), and Johannes von Mikulicz-Radecki (1850-1905), established bacteriological laboratories within their hospital clinics. By testing for the presence of bacteria on individuals and even entire hospitals, bacteriologists could audit the efficacy of aseptic or antiseptic measures. In this way, von Mikulicz-Radecki proved that speaking during operations encouraged droplet infection (a term coined by him).

1890, the American surgeon, William S Halsted (1852-1922), introduced rubber gloves • This could be minimised by wearing face masks (except when the surgeon was bearded). • However, in 1890, the American surgeon, William S Halsted (1852-1922), introduced rubber gloves. These were initially worn by his operating room nurse, Caroline Hampton, (who was also his fiancée) because she developed eczema of the hands from the carbolic acid and bichloride of mercury solutions used as antiseptics. Halstead asked the Goodrich Rubber Company to make special surgical gloves. The first batch reached the elbow. By the final years of the century, aseptic and antiseptic techniques were adopted in one combination or another by all surgeons.

Surgeons adopt aseptic techniques c. 1875 • In this photograph, the surgeon, Sir Victor Horsley (1857-1916), is standing on the left wearing a face mask and rubber gloves although he is the only person in the operating theatre to do so. The others are wearing outdoor clothes under gowns or white coats while the nurses wear standard ward uniforms. In addition, Horsley's abdomen was encased in antiseptic dressings in preparation for the removal of his appendix the following day!

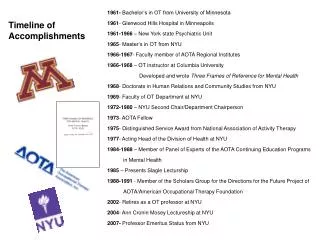

Breakthrough dates in XX century • 1954-Joseph Murray performsfirst kidney transplant • 1962 Charnley pioneers joint replacement • 1964 Coronary bypass surgery • 1967 First heart transplant • 1990 Development of day-case surgery

Anaesthesiology - from curare to pain clinics • In 1926, the American anaesthetist, John Lundy (1894-1973), first used the term 'balanced anaesthesia' to describe a combination of several agents to produce optimum anaesthesia and analgesia. During the early 1930s, he and other researchers in Germany investigated a number of narcotic compounds which led to the development of intravenous and intramuscular anaesthesia. These could be used for short procedures as well as for pre-medication. They were improved during the 1960s with the introduction of the barbiturate-free benzodiazepines such as diazepam. Intra-operative muscle relaxation made abdominal surgery easier. Curare, the South American arrow poison, was given in 1942 to a patient undergoing appendectomy. The anaesthetist, Harold Griffith (1894-1985) of Montreal, administered the anaesthetic gas through an endotracheal tube as the patient's abdominal and thoracic muscles were completely paralysed.

Curare-like substances were further developed by 1948. Anaesthesiology increasingly aimed to individualise anaesthetics for each patient, taking into account the type of procedure, age, body weight, any underlying condition (eg. diabetes, high blood pressure, kidney failure), as well as the physiological effects of peri-operative stress. The risk of thrombosis and embolism in high risk patients was markedly diminished from the early 1970s by prophylactic anticoagulants such as heparin, purified in 1929 by Charles Best (1899-1978) of Toronto who had assisted Frederick Banting (1891-1941) in the discovery of insulin. Heparin was first used in Sweden and the USA. The development of artificial hypothermia, controlled lowering of blood pressure to diminish blood loss, and extracorporeal circulation via the heart-lung machine, enabled increasingly complex surgical procedures to be performed.

Spinal, epidural, and nerve block analgesia became increasingly effective so as to replace gas-induced anaesthesia in operations such as caesarian section and prostatectomy. Advances in analgesia techniques helped develop day-case surgery whereby minor procedures were performed on an out-patient basis. Anaesthestists, like surgeons, began to specialise in particular areas such as paediatrics, transplantation, heart surgery, intensive care, and pain management. Pain clinics were established in hospitals during the 1980s for assessing and treating patients with chronic or intractable pain.