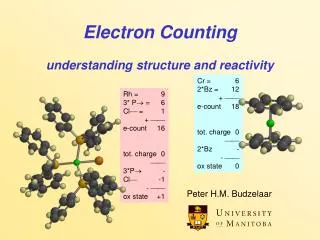

Electron Counting understanding structure and reactivity

521 likes | 1.73k Vues

Electron Counting understanding structure and reactivity. Cr = 6 2*Bz = 12 + ¾¾ e-count 18 tot. charge 0 ¾¾ 2*Bz - - ¾¾ ox state 0. Rh = 9 3* P ® = 6 Cl ¾ = 1 + ¾¾ e-count 16 tot. charge 0 ¾¾ 3*P ® - Cl ¾ -1 - ¾¾ ox state +1. Peter H.M. Budzelaar.

Electron Counting understanding structure and reactivity

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Electron Countingunderstanding structure and reactivity Cr = 62*Bz = 12 + ¾¾ e-count 18 tot. charge 0 ¾¾ 2*Bz - - ¾¾ ox state 0 Rh = 93* P® = 6 Cl¾ = 1 + ¾¾ e-count 16 tot. charge 0 ¾¾ 3*P® - Cl¾ -1 - ¾¾ ox state +1 Peter H.M. Budzelaar

Why count electrons ? • Basic tool for understanding structure and reactivity. • Simple extension of Lewis structure rules. • Counting should be “automatic”. • Not always unambiguousÞ don’t just follow the rules, understand them! Electron Counting

Predicting reactivity Electron Counting

Predicting reactivity 16-e PdII 16-e PdII 18-e PdII Most likely associative: Electron Counting

Predicting reactivity Electron Counting

Predicting reactivity Almost certainly dissociative: 16-e Cr(0) 18-e Cr(0) 18-e Cr(0) Electron Counting

The basis of electron counting • Every element has a certain number of valence orbitals: 1 { 1s } for H 4 { ns, 3´np } for main group elements 9 { ns, 3´np, 5´(n-1)d } for transition metals s px py pz dxy dxz dyz dx2-y2 dz2 Electron Counting

The basis of electron counting • Every orbital wants to be “used", i.e. contribute to binding an electron pair. • Therefore, every element wants to be surroundedby 1/4/9 electron pairs, or 2/8/18 electrons. • For main-group metals (8-e), this leads to the standard Lewis structure rules. • For transition metals, we get the 18-electron rule. • Structures which have this preferred count are calledelectron-precise. Electron Counting

Compounds are not alwayselectron-precise ! The strength of the preference for electron-precise structures depends on the position of the element in the periodic table. • For very electropositive main-group elements, electron count often determined by steric factors. • How many ligands "fit" around the metal? • "Orbitals don't matter" for ionic compounds • Main-group elements of intermediate electronegativity (C, B) have a strong preference for 8-e structures. • For the heavier, electronegative main-group elements, there is the usual ambiguity in writing Lewis structures (SO42-: 8-e or12-e?). Stable, truly hypervalent molecules (for which every Lewis structure has > 8-e) are not that common (SF6, PF5). Structures with < 8-e are very rare. Electron Counting

Compounds are not alwayselectron-precise ! The strength of the preference for electron-precise structures depends on the position of the element in the periodic table. • For early transition metals, 18-e is often unattainable for steric reasons The required number of ligands would not fit. • For later transition metals, 16-e is often quite stable In particular for square-planar d8 complexes. • For open-shell complexes, every valence orbital wants to be used for at least one electron More diverse possibilities, harder to predict. Electron Counting

Prediction of stable complexes Cp2Fe, ferrocene: 18-e Very stable. Behaves as an aromaticorganic compound in e.g.Friedel-Crafts acylation. Cp2Ni, nickelocene: 20-e Chemically reactive,easily loses a Cp ring,reacts with air. Cp2Co, cobaltocene: 19-e Strong reductant,reacts with air. Cation (Cp2Co+) is very stable. Electron Counting

If there are not enough electrons... • Structures with a lower than ideal electron count are calledelectron-deficient or coordinatively unsaturated. • They have unused (empty) valence orbitals. • This makes them electrophilic,i.e. susceptible to attack by nucleophiles. • Some unsaturated compounds are so reactivethey will attack hydrocarbons, or bind noble gases. Electron Counting

Reactivity of electron-deficient compounds 18-e Fe(0)unreactive 16-e Fe(0)very reactive 18-e Fe(0) Electron Counting

If there are too many electrons... • "Too many electrons" means there are fewer net covalent bonds than one would think. • Since not enough valence orbitals available for these electrons. • An ionic model is required to explain part of the bonding. • The "extra" bonds are relatively weak. • Excess-electron compounds are relatively rare,especially for transition metals. • Often generated by reduction (= addition of electrons). Electron Counting

Where are the electrons ? • Electrons around a metal can be in metal-ligand bonding orbitalsor in metal-centered lone pairs. • Metal-centered orbitals are fairly high in energy. • A metal atom with a lone pair is a s-donor (nucleophile). • susceptible to electrophilic attack. Electron Counting

Metal-centered lone pairs Basicity of Cp2WH2 comparable to that of ammonia! 18-e WIV 18-e WVI Electron Counting

How do you count ? "Covalent" count: • Number of valence electrons of central atom. • from periodic table • Correct for charge, if any. • but only if the charge belongs to that atom! • Count 1 e for every covalent bond to another atom. • Count 2 e for every dative bond from another atom. • no electrons for dative bonds to another atom! • Delocalized carbon fragments: usually 1 e per C • Three- and four-center bonds need special treatment. • Add everything. There are alternative counting methods (e.g. "ionic count").Apart from three- and four-center bonding cases,they should always arrive at the same count.We will use the "covalent" count in this course. Electron Counting

Starting simple... N = 53* H¾ = 3 + ¾¾ e-count 8 H = 1H¾ = 1 + ¾¾ e-count 2 N has a lone pair.Nucleophilic! C = 44* H¾ = 4 + ¾¾ e-count 8 C = 42* H¾ = 2 2* C¾ = 2 + ¾¾ e-count 8 A double bond countsas two covalent bonds. Electron Counting

Predicting reactivity C = 4+ chg = -1 3* H¾ = 3 + ¾¾ e-count 6 C = 42* H¾ = 2 + ¾¾ e-count 6 "Singlet carbene". Unstable.Sensitive to nucleophiles (empty orbital) and electrophiles (lone pair). Highly reactive,electrophilic. C = 4- chg = +1 3* H¾ = 3 + ¾¾ e-count 8 "Triplet carbene". Extremelyreactive as radical, notespecially for nucleophilesor electrophiles. Saturated, butnucleophilic. Electron Counting

When is a line not a line ? is C = 43* H¾ = 3 C¾ = 1 + ¾¾ e-count 8 or B = 3- chg = +1 3* H¾ = 3 N¾ = 1 + ¾¾ e-count 8 N = 5+ chg = -1 3* H¾ = 3 B¾ = 1 + ¾¾ e-count 8 B = 33* H¾ = 3 N® = 2 + ¾¾ e-count 8 N = 53* H¾ = 3 + ¾¾ e-count 8 Electron Counting

Covalent or dative ? 1 e dativebond 2 e covalentbond "bond" to theallyl fragment 3 e How do you know a fragment forms a covalent or a dative bond? • Chemists are "sloppy" in writing structures. A "line" can mean a covalent bond, a dative bond, or even a part of a three-center two-electron bond. • Use analogies ("PPh3 is similar to NH3"). • Rewrite the structure properlybefore you start counting. Pd = 10Cl¾ = 1 P® = 2 allyl = 3 + ¾¾ e-count 16 Electron Counting

Handling 3c-2e and 4c-2e bonds A 3c-2e bond can be regarded as a covalent bond "donating" its electron pair to a third atom. Rewriting it this way makes counting easy. B2H6 is often written as . But it cannot have 8 covalent bonds: there are only 12 valence electrons in the whole molecule! The central B2H2 core is held together by two 3c-2e bonds: Electron Counting

Handling 3c-2e and 4c-2e bonds 2 e 1 e Rewrite bonding in terms of two BH3 monomers: This is one of the few cases where Crabtree does things differently(for transition metals). The method shown here is closer to the actual VB description of the bonding. B = 33* H¾ = 3 BH® = 2 + ¾¾ e-count 8 C2H6 BH3NH3 B2H6 Electron Counting

What kind of bridge bond do I have ? A methyl group can formone more single bond. Afterthat, it has no lone pairs, so thebest it can do is share the Al-C bonding electrons with asecond Al: After chlorine forms a single bond,it still has three lone pairs left.One is used to donateto the second Al: Al = 33* Me¾ = 3 MeAl® = 2 + ¾¾ e-count 8 Al = 33* Cl¾ = 3 Cl® = 2 + ¾¾ e-count 8 A 3c-2e bond will only form when the central (bridging) atomdoes not have any lone pairs. When lone pairs are available, they are preferred as donors. Electron Counting

3c-2e vs normal bridge bonds • The orbitals of a 3c-2e bond are bondingbetween all three of the atoms involved. • Therefore, Al2Me6 has a netAl-Al bonding interaction. • The orbitals involved in "normal" bridgesare regular terminal-bridge bonding orbitals. • Thus, Al2Cl6 has strong Al-Cl bondsbut no net Al-Al bonding. Electron Counting

Handling charges "Correct for charge, if any, but only if it belongs to that atom!" How do you know where the charge belongs? Eliminate all obvious places where a charge could belong,mostly hetero-atoms having unusual numbers of bonds. What is left should belong to the metal... Any alkyl-SO3 groupwould normally be anionic(c.f. CH3SO3-, the anion of CH3SO3H). So the negative chargedoes not belong to the metal! Rh = 9CH2¾ = 1 3* CO® = 6 + ¾¾ e-count 16 Electron Counting

Handling charges Even overall neutral molecules could have "hidden" charges! A boron atom with 4 bondswould be -1 (c.f. BH4-). No other obvious centers ofcharge, so the Co must be +1. Co = 9 + chg = -13* P® = 6 2* CO® = 4 + ¾¾ e-count 18 Electron Counting

A few excess-electron examples PCl5 • P would have 10 e, but only has 4 valence orbitals,so it cannot form more than 4 “net” P-Cl bonds.You can describe the bonding using ionic structures("negative hyperconjugation"). • Easy dissociation in PCl3 en Cl2."PBr5" actually is PBr4+Br- ! SiF62-, SF6, IO65- andnoble-gas halides canbe described in asimilar manner. P = 5+ chg = -1 4* Cl¾ = 4 + ¾¾ e-count 8 P = 55* Cl¾ = 5 + ¾¾ e-count 10 Electron Counting

A few excess-electron examples HF2- • H only has a single valence orbital,so it cannot form two covalent H-F bonds! • Write as FH·F-, mainly ion-dipole interaction. This is just an extreme form ofhydrogen bonding. Most otherH-bonded molecules haveless symmetric hydrogen bridges. H = 1- chg = +1 2* F¾ = 2 + ¾¾ e-count 4 H = 11* F¾ = 1 + ¾¾ e-count 2 Electron Counting

Does it look reasonable ? Remember when counting: • Odd electron counts are rare. • In reactions you nearly always go from even to even (or odd to odd), and from n to n-2, n or n+2. • Electrons don’t just “appear” or “disappear”. • The optimal count is 2/8/18 e. 16-e also occurs frequently, other counts are much more rare. Electron Counting

Electron-counting exercises Me2Mg Pd(PMe3)4 MeReO3 ZnCl4 Pd(PMe3)3 OsO3(NPh) ZrCl4 ZnMe42- OsO4(pyridine) Co(CO)4- Mn(CO)5- Cr(CO)6 V(CO)6- V(CO)6 Zr(CO)64+ PdCl(PMe3)3 RhCl2(PMe3)2 Ni(PMe3)2Cl2 Ni(PMe3)Cl4 Ni(PMe3)Cl3 Electron Counting

Oxidation states Most elements have a clear preference for certain oxidation states. These are determined by (a.o.) electronegativity and the number of valence electrons. Examples: Li: nearly always +1.Has only 1 valence electron, so cannot go higher.Is very electropositive, so doesn’t want to go lower. Cl: nearly always -1.Already has 7 valence electrons, so cannot go lower.Is very electronegative, so doesn’t want to go higher. Electron Counting

Calculating oxidation states Rewrite compound as if all bonds were fully ionic/dative, i.e. the electron pairs of each bond go to one end of the bond. Which end? Use electronegativity to decide. Ignore homonuclear covalent bonds No unambiguous choice available Usually end up with a unique set of charges The "Lewis structure ambiguity" for hypervalent compounds does not cause problems here Electron Counting

How do you calculate oxidation states ? • Start with the formal charge on the metal See earlier discussion in "electron counting" • Ignore dative bonds • Ignore bonds between atoms of the same element This one is a bit silly and produces counterintuitive results • Assign every covalent electron pair to the most electronegative element in the bond: this produces + and – charges Usually + at the metal Multiple bonds: multiple + and - charges • Add Electron Counting

Examples - main group elements no chg = 0 4* Cl-¾C+ = +4 + ¾¾ ox st +4 - chg = -1 4* Cl-¾Al+ = +4 + ¾¾ ox st +3 no chg = 0 2* Cl-¾C+ = +2 O2-=C2+ = +2 + ¾¾ ox st +4 Electron Counting

Examples - transition metals 2- chg = -2 4* Cl-¾Pd+ = +4 + ¾¾ ox st +2 no chg = 0 1* O-¾Mn+ = +1 3* O2-=Mn2+ = +6 + ¾¾ ox st +7 - chg = -1 4* O2-=Mn2+ = +8 + ¾¾ ox st +7 Electron Counting

Examples - homonuclear bonds no chg = 0 3* Cl-¾C+ = +3 1* C¾C = 0 + ¾¾ ox st +3 2- chg = -2 3* Cl-¾Pt+ = +3 1* Pt¾Pt = 0 + ¾¾ ox st +1 Artificial, abnormal formal oxidation states. If you want to say something about stability,pretend the homonuclear bond is polar(for metals, typically with the + end at the metal you are interested in).For the above examples, that would give C(+4) and Pt(+2), very normal oxidation states. Electron Counting

Example - handling 3c-2e bonds Rewrite first, as discussed under "electron counting".The rest is "automatic" (ignore the dative bonds as usual). no chg = 0 3* H-¾B+ = +3 + ¾¾ ox st +3 Electron Counting

Oxidation state and stability Sometimes you can easily deduce that an oxidation state is "impossible", so the compound must be unstable no chg = 0 4* Me-¾Mg+ = +4 + ¾¾ ox st +4 But Mg only has 2 valence electrons!Any compound containing Mg4+ will not be stable. Electron Counting

Significance of oxidation states Oxidation states are formal. They do not indicate the "real charge" at the metal centre. However, they do give an indication whether a structure or composition is reasonable. apart from the M-M complication They have more meaning when all bonds are relatively polar. i.e. close to the fully ionic description used for counting Electron Counting

Normal oxidation states For group n or n+10: • never >+n or <-n (except group 11: frequently +2 or +3) • usually even for n even, odd for n odd • usually ³ 0 for metals • usually +n for very electropositive metals • usually 0-3 for 1st-row transition metals of groups 6-11, often higher for 2nd and 3rd row • electronegative ligands (F,O) stabilize higher oxidation states,p-acceptor ligands (CO) stabilize lower oxidation states • oxidation states usually change from m to m-2, m or m+2 in reactions Electron Counting

Oxidation-state exercises Calculate oxidation states for the metal in the complexes below.From this and the electron count (done earlier),draw conclusions about expected stability or reactivity. Me2Mg Pd(PMe3)4 MeReO3 ZnCl4 Pd(PMe3)3 OsO3(NPh) ZrCl4 ZnMe42- OsO4(pyridine) Co(CO)4- Mn(CO)5- Cr(CO)6 V(CO)6- V(CO)6 Zr(CO)64+ PdCl(PMe3)3 RhCl2(PMe3)2 Ni(PMe3)2Cl2 Ni(PMe3)Cl4 Ni(PMe3)Cl3 Electron Counting

Coordination number and geometry The coordination number is the number of atoms directly bonded to the atom you are interested in regardless of bond orders etc often abbreviated as CN CH4: 4 C2H4: 3 C2H2: 2 AlCl4-: 4 Me4Zn2-: 4 OsO4: 4 B2H6: 4 (B) 1 (terminal H) 2 (bridging H) Electron Counting

p-system ligands For complexes with p-system ligands, the whole ligand is usually counted as 1: Cyclopentadienyl groups are sometimes counted as 3,because a single Cp group can replace 3 individual ligands: CN 4 CN 3 or 5 Electron Counting

Common coordination numbers The most common coordination numbers for organometallic compounds are: • 2-6 for main group metals • 4-6 for transition metals Coordination numbers >6 are relatively rare, as are very low coordination numbers (<4) together with a “too-low” electron count. Abnormally high coordination numbers are found for "polyhydrides", where there is often ambiguity between "hydride" and "dihydrogen" descriptions the low steric requirements of H make this possible example given later on Electron Counting

Coordination number and geometry C.N. "Normal" geometry 2 linear or bent 3 planar trigonal, pyramidal; "T-shaped" often for d8 14-e 4 tetrahedral; square planar often for d8 16-e 5 square pyramidal, trigonal bipyramidal 6 octahedral Exceptions can be expected for abnormal electron counts or for ligands with unusual geometric requirements Electron Counting

Example: protonation of WH6(PMe3)3 Could WH6(PMe3)3be a true polyhydride ? Count: 18-e (OK). Oxidation state: 6 (OK). CN: 9 (very high). Possible. Electron Counting

Example: protonation of WH6(PMe3)3 Protonation gives WH7(PMe3)3+.Could that still bea true polyhydride ? Count: 18-e (OK). Oxidation state: 8 (too high). CN: 10 (extremely high). Virtually impossible. W+ has only 5 electronsbut must form 7 W-H bonds ! This is almost certainlya dihydrogen complex. Electron Counting