Environmental Valuation using Revealed Preference Methods

420 likes | 1.09k Vues

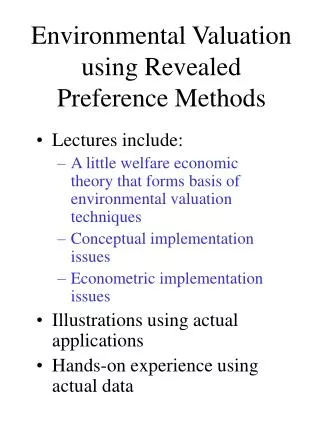

Environmental Valuation using Revealed Preference Methods. Lectures include: A little welfare economic theory that forms basis of environmental valuation techniques Conceptual implementation issues Econometric implementation issues Illustrations using actual applications

Environmental Valuation using Revealed Preference Methods

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Environmental Valuation using Revealed Preference Methods • Lectures include: • A little welfare economic theory that forms basis of environmental valuation techniques • Conceptual implementation issues • Econometric implementation issues • Illustrations using actual applications • Hands-on experience using actual data

Why are there so many more stated preference than revealed preference studies? • Less statistical knowledge necessary? (perhaps?) • RP can’t handle existence value? (not always relevant) • Nature conspires against revealed preference methods

What Concepts Do We Need? • A theoretical model of how people make decisions in some environmentally related context • A means of relating this behavior to a well-defined welfare measure • A means of obtaining consistent estimates of the parameters of the behavioral functions • A mathematical relationship between the parameters and the welfare measure

What Data/Circumstances Do We Need for RP Methods to have a Chance? • Behavior “footprints” – environmental change must influence some behavior • Behavioral change must constitute most of, and not more than, a response to environmental change • Behavior must relate to money prices

Stated and Revealed Preference • Stated preference methods • very sensitive to way ask question • not so sensitive to econometric specification • Revealed preference • not so sensitive to data collection methods • very sensitive to econometric specification

Why? • In SP you are asking people directly for their values • In RP you are asking people for facts and then you are deducing values based on models of behavior

Types of Environmental Amenities/Goods that Are Often Valued Using Revealed Preference • Natural, preserved sites (e.g. parks, nature-based recreational areas) • Environmental quality or amenities at these sites • Ambient environmental quality/risks (at the individual’s residential location) • Environmental quality/risks at individual’s work-site • Environmental inputs into production

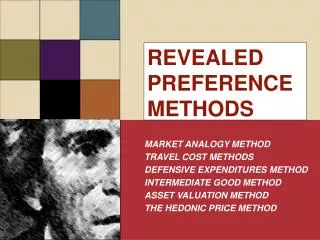

Empirical Models • Natural sites • Single site demand models • Random utility models • Site environmental quality • Systems of demand functions • Random utility models • Ambient environmental quality • Hedonic models • Averting behavior models • Random utility models • Job-related environmental qual. • Hedonic models • Averting behavior models • Random utility models • Inputs into production • Supply/demand functions • Random utility models

Theoretical Restrictions and Models • The environment as an input into production • Household production • Firm’s profit maximization (sometimes under risk and uncertainty) • The environment as a “weak complement” to privately consumed goods: • Household production models of single goods • Random utility models of choice • The environment as a quality characteristic of a marketed good – • hedonic models

Cases we will look at in this course Valuing: • Existence of a site using a single site recreation demand model • Environmental amenity using a random utility model • Environmental good as an input into fisheries production using a random utility model [ Environmental quality as a characteristic of a marketed good – Dr. Tyrvainen ]

Notation – the utility maximization problem Individual is assumed to: Max U(q) + (y - pq) where U=utility q=vector of privately consumed goods p=corresponding vector of prices y=income =LaGrangian multiplier

Notation – important functions in welfare economics Indirect utility function: v(p,y) = U(q) + (y - pq) Expenditure function: m(p,U) =min pq+(U0-U(q))

Conventional measures of benefits and losses (applied “welfare” measures) Compensating variation (CV) = amount of money necessary to “compensate” for an exogenous change in circumstances Suppose a price changes, p10p11 Then CV of change is defined implicitly as: v(p10,p-10,y)=v(p11,p-10,y-CV) CV is signed here according to the direction of the welfare change.

Compensating variation in terms of expenditure function CV is an explicit function in terms of expenditure function:

Importance of Shepherd’s Lemma in Standard Welfare Analysis Partial derivative of m equals compensated demand: Price CV measure p10 p11 Compensated demand function q10 q11 Quantity

Usually observe Marshallian demands, but.. Results that relate the consumer surplus (CS) and compensating variation (CV): • If income effects are negligible, then CS = CV • Can bound CV by a function of income elasticities and CS (Willig) • Can integrate back from Marshallian function to expenditure function

Valuing a change in an environmental good Suppose “b” is our environmental amenity. If individuals care about b for whatever reason, it will show up in the expenditure function. CV measure for a change in b is: CV = m(p0,b0,U0)-m(p0,b1,U0)

How can we get an approximation of this? • From this point on there is no general theory. There is no analog to Shepherd’s lemma for environmental quality changes. is typically not a behavior function • There are only strategies that: • may or may not be applicable (depending on nature of behavior) • may or may not be feasible (depending on availability of data)

Valuing the Existence of a (Natural) Site If b denotes the site, in the sense that b=1 means the site exists, then the individual’s general model is: Max U(q,b) + (y-pq) But unless there is some further restrictions on this problem, there is no hope of using RP to value b.

A simple way to frame the problem: The individual only cares about the existence of the site if he visits the site (weak complementarity). The individual derives utility from visiting the site. A demand curve for site visits can be constructed using access costs as price. Elimination of the site is equivalent to pricing access high enough so no trips are taken.

Could Cast in Household Production Framework max U(q,z(b,x))+(y-pq-rx) where q=other goods z=household produced good(trips to site) b=index of site’s existence x=other inputs into production of trips to site r=input prices

Welfare measure is “simple” Treat as a “price” change from existing price (marginal cost) to “choke” price. constant marginal cost of producing z CV (or CS) measure of value of site Implicit demand function for household produced z z0 quantity of visits

Issues of Implementation • Specification Issues: • Time Allocation • Substitution • Estimation Issues: • Censored Samples • Truncated Samples

Specification Issue #1: Value of Time Models of recreational demand are really household production models. Household production models are about allocating both money and time.

Household Production Including Time Allocation Maximization decision is now: The household production function now includes time spent in taking trips. The money constraint explicitly takes account of labor time.

Valuing time as function of wage rate If people can easily substitute work for leisure, then the opportunity cost of time is (after-tax) wages and two constraints collapse into one: Full income Full price

Corner and Interior Solutions in Labor Market If some people have fixed work times, then work/leisure substitution may not be easy. In these cases, time constraint does not collapse into money constraint and two constraints remain.

Some Labor Market Solutions INTERIORSOLUTION Money indifference curve Slope=wage rate Earned income =w*h Leisure T=total available time h=labor CORNER SOLUTION Money Slope=wage rate of secondary job Earned income =w*h Slope=implicit wage rate of primary job Leisure T=total available time h=labor

In Practice…. • Labor market model has better theoretical basis, but… • Difficult to determine which respondents have flexible time • Sometimes multicollinearity between time and money costs if included separately in model • “Ad hoc” opportunity cost of time model often values time at some fraction of the wage rate(e.g. .4 or .5 – may change with different tax rates)

What happens if ignore time costs? Since time costs and money costs are generally correlated, leaving out time will cause an upward bias in the coefficient on money costs. “True” model is: But you estimate:

If measuring value of site… with a linear demand function… Constant marginal cost of z “true” 1/1 biased 1/1 estimate z Number of trips (Note: since the dependent variable in the model is trips, the slope of the line in the graph is really 1/1). Consumer surplus = Consumer surplus is underestimated

If measuring value of site… with a semi-log demand function, consumer surplus = -z/1 Estimate of CS will also be biased downward if your estimate of 1 is biased upward.

Specification issue #2: Demand function for z should include money and time costs (and environmental quality) of substitutes. If substitutes left out and these are correlated over the sample with the “own” money and time costs (and quality), then estimates will be biased.

Suppose there are two sites, A and B, that are substitutes in recreation. As you look across observations on people who visit these sites, suppose people who live far from one site also tend to live relatively far from the other site. Now, suppose you make the mistake of estimating the demand for trips to site A without including costs to site B. Cost of accessing site A Biased estimate Trips to site A

Baltimore, MD Washington, DC Beach Areas Population density: Blue – highest Yellow - lowest