Chapter 4 Syntax

890 likes | 1.23k Vues

Introduction to Linguistics. Chapter 4 Syntax. Instructor: Liu Chengyu School of Foreign Languages, Southwest University. 4.1. 4.2. 4.3. 4.4. 4.5. 4.6. 4.7. Contents. Introduction. Word classes. The Prescriptive Approach. The Descriptive Approach. Constituent Structure Grammar.

Chapter 4 Syntax

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Introduction to Linguistics Chapter 4 Syntax Instructor: Liu Chengyu School of Foreign Languages, Southwest University

4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Contents Introduction Word classes The Prescriptive Approach The Descriptive Approach Constituent Structure Grammar Transformational Grammar Systemic Functional Grammar

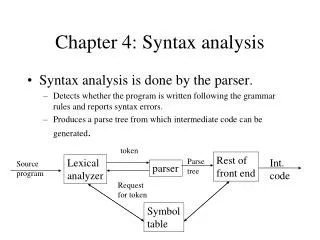

4.1 Introduction • In the previous lecture, we have studied morphology, the structure of words. When we put words together to form sentences, we also get a structure. If we focus on the structure and ordering of components within a sentence, we are studying what is known as the syntax of a language.

Morphology is concerned with the internal composition of a word. • Syntax is concerned with combination of words.

meaning of a sentence • the meaning of the words of which it is composed • the structure of the sentence, such as word order.

(1) a. The hunter fears the cries of the blackbirds. b. The blackbirds fear the cries of the hunter. Clearly, (1a) and (1b) do not have the same meaning.

(2) a. Jack looked up the word. b. Jack looked the word up. Sometimes, however, a change of word order does not influence meaning.

(3) * Cries fear the the of hunter blackbirds the. (The asterisk * is often used to indicate that a structure is ill-formed, or ungrammatical.) • The grammars of all languages include rules of syntax which reflect the speaker’s knowledge of these facts. The rules of syntax also explain the fact that although a sequence like (3) is made up meaningful words, it has no meaning.

Sequences of words that observe the rules of syntax are said to be well formed or grammatical and those which violate the syntactic rules are therefore ill formed and ungrammatical.

unacceptable acceptable 4.2 Word Classes a. Cries fear the the of hunter blackbirds the. b. The hunter fears the cries of the blackbirds. • What we are here concerned with is the grammatical structure.

Whether a word can occupy a certain position in a sentence depends on its grammatical category rather than its meaning. We can replace fear and cries by admire and speed respectively and the sentence is still grammatical, because both have been replaced by a word of the same category.

The categories are traditionally called parts of speech, but now they are generally called word classes.

Now we can put our sentence into classes. (1) a. The hunter fears the cries of the blackbirds. S → art., N, V, art., N, prep., art., N.

acceptable unacceptable a. the very pretty girl the order “art., adv., adj., N” b. *pretty the very girlthe order “adj., art., adv., N”

The rules which govern the structure of phrases are known as phrase structurerules or rewrite rules. Such rules allow for the generation of grammatical sentences in a language; they constitute a generative grammar for that language.

4.3 The Prescriptive Approach • Some grammarians, mainly in eighteenth-century England, lay down rules for the correct or “proper” use of English. (1)You must not split infinitives. (2)You must not end a sentence with a preposition.

This view of grammar as a set of rules for the “proper” use of a language is still to be found today and may be best characterized as the prescriptive approach.

It is valuable for us to be aware of the “proper” use of the language. If it is a social expectation that someone who writes well should obey these prescriptive rules.

However, we should note that it does not mean that these prescriptive rules cannot be broken. In spoken English, for example, split infinitives as to boldly go instead of to go boldly or boldly to go are used sometimes.

4.4 The Descriptive Approach • Throughout the 20th century, linguists collect samples of the language they are interested in and attempt to describe the regular structures of the language as it is used, not according to some view of how it should be used. This is called the descriptive approach.

4.4.1 Structural analysis • One type of descriptive approach is called structural analysis. Its main objective is to study the distribution of linguistic forms in a language.

car, radio, child, etc. noun • The method involves the use of “test-frames”. (4) The _____ makes a lot of noise. • All these linguistic forms fit in the same test-frame, they are likely to belong to the same grammatical category, i.e. noun.

Thus, we need different test-frames for these linguistic forms, which could be like the following: (6) ______ makes a lot of noise. (7) I heard a ______ yesterday.

By developing a set of test-frames of this type and discovering what forms fit the slots in the test-frames, we can produce a description of some aspects of the sentence structures of a language.

4.4.2 Immediate Constituent Analysis • Another approach with the same descriptive purposes is called immediate constituent analysis (IC analysis). This is simply the idea that linguistic units can be parts of larger constructions and may themselves also be constructions composed of smaller parts.

These constituents can in turn be further analyzed into smaller constituents, such as noun phrases analyzed into an article and a noun. This process continues until no further divisions are possible. The first divisions or cuts are known as the immediate constituents (ICs), and the final cuts as theultimate constituents (UCs).

We can identify five constituents at the word level. (8) The man bought a car. Noun Phrase (NP) Verb Phrase (VP)

Why, for instance, do we class the man and bought a car as constituents rather than man bought and bought a? The answer is that whether or not a sequence is a constituent is judged by itssubstitutability. The technical term used for this substitution test is expansion.

For example, the man in (8) can be replaced by the pronoun he. The fact that there is a separate element to substitute for the man shows that it is a constituent of English. No element exists that can be substituted for bought a or man bought a, which are not constituents. (8) The man bought a car.

The best way to show IC is to use a tree diagram. • The man bought a car

Brackets can also be used but are arguably less easy to read. For example: (9) a. [the man bought a car] b. [[the man] [bought a car]] c. [[[the] [man]] [[bought] [a car]]] d. [[[the] [man]] [[bought] [[a] [car]]]]

This approach to divide the sentence up into its immediate constituents by using binary cutting until obtaining its ultimate constituents is called immediate constituent analysis.

Cutting sentences into their constituents can show up and distinguish ambiguities, as in the case of the ambiguous phrase old men and women, which may either refer to old men and women of any age or to old men and old women.

old men and women old men and women • Cutting sentences into their constituents can show up and distinguish ambiguities, as in the case of the ambiguous phrase old men and women, which may either refer to old men and women of any age or to old men and old women.

4.5 Constituent Structure Grammar • A grammar which analyzes sentences using only the idea of constituency, which reveals a hierarchy of structural levels, is referred to as a constituent structure grammar or constituent structure syntax .

There are a number of ways that sentences or strings can be cut up into constituents. The principles used may vary but the process is usually referred to as “labelling and bracketing”.

(10) S NP VP Art N V NP Art N The man bought a car

(11) S NP V NP Art N Art N The man bought a car • There an alternative analysis.

These analyses emphasize different aspects of structure. The first shows only binary cutting and gives a consistent phrasal structure. The second gives greater emphasis to the verb as a central element in sentence structure.

For convenience and consistency, in this section, we shall consider a constituent structure that is called phrase structure—used in early transformational grammar. • S→NP+VP • VP→Vtr. +NP • NP→Art.+N • Vtr. →buy, sell, build, repair, wash, etc. • N→man, woman, car, house, bicycle, etc. • Art→a, an, the

Even such a very simple set of rules allows us to produce quite a few sentences in English. We can produce sentences like: (12) a. The man bought a car. b. The man sold a car. c. The woman repaired the bicycle.

We can have other rules to account for such structures and for other types of structure. For instance, if we change the rules to account for adverbs (Adv) and prepositional phrases (PP), then we can generate a larger number of sentences.

Vtr. →buy, sell, etc. • N→man,car, etc • Art→a, the, etc. • Prep→in, on, etc. • S→NP+VP (+Adv) • VP→Vtr. +NP • NP→Art+N (+PP) • PP→Prep+NP • Adv→ adverbs of place etc. PP

In the above rules, the normal brackets ( ) show that the constituent is optional, the curly brackets { } show that we may choose one constituent or the other. We can now generate sentences like: (13)a. The man sells the car in the garage. b. The woman washes the bicycle in the street. c. The boy repairs the bicycle in the house.

This tree diagram means that the boy repairs the bicycle while he was in the house. (14) S NP VP Adv Art N V NP Prep NP Art N Art N The boy repairs the bicycle in the house • 14.

This tree diagram means that the boy repairs the bicycle which is in the house. (15) S NP VP Art N V NP Art N PP Prep NP Art N The boy repairs the bicycle in the house

The rules introducing prepositional phrases also introduce the important concept of recursion. (16) This is the house that Jack built. This is the cat that lived in the house that Jack built. This is the dog that chased the cat that lived in the house that Jack built. …

2 1 • There are a number of features of language that constituent structure analysis may not be able to account for. We shall consider two. Elements in a construction can be discontinuous. What is the relationship between sentences that seem to be closely connected.

1 a. The boy cleaned the room up. b. The student looked the word up in the dictionary. In both of these sentences the particle up is closely linked to the verb but is not immediately adjacent to it. Such relationships are not clearly or easily shown in constituent structure tree diagrams because their positions are discontinuous.