Libel and Ethics

460 likes | 820 Vues

Libel and Ethics. -- How to stay out of court -- How to build an ethics toolbox. Libel: In fall 2007 …. Illinois Chief Justice Robert Thomas agreed to a $3 million settlement – he initial was awarded $7 million – after winning a libel lawsuit against

Libel and Ethics

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Libel and Ethics -- How to stay out of court -- How to build an ethics toolbox

Libel: In fall 2007 … Illinois Chief Justice Robert Thomas agreed to a $3 million settlement – he initial was awarded $7 million – after winning a libel lawsuit against the Kane County Chronicle, a suburban Chicago newspaper and former columnist Bill Page. Supposedly, the paper and Page issued apologies, but Page denied that. ``That apology runs after my signature,'' he said. ``I stand by everything I wrote, and I would repeat it. I'm not backing down from this.'' The chief justice was satisfied with the settlement. ``They've apologized for what they have done. The case is over,'' he said. Page wrote a series of columns in 2003 accusing Thomas of softening his position in a disciplinary hearing of a prosecutor after her supporters backed a judicial candidate Thomas favored. Since 1986, judges have won eight of 11 cases in which they have sued news media, according to the Media Law Resource Center in New York. Dozens of other cases brought by judges were dismissed before trial, said center staff attorney David Heller.

What is libel? Libel is a false statement printed or broadcast about a person that tends to bring that person into public hatred, contempt or ridicule. Other than falsehood, three other elements constitute libel, which you can remember by the acronym DIP: 1. Defamation 2. Identification 3. Publication

What is libel? Why isn’t a story on the arrest of Courtney Love on drunken driving charges considered libelous? It’s defamatory, the person’s name is given and it’s published. Associated Press photo

What is libel? The actions of agents of the government are protected under privilege, plus the police are public officials. More on that in a bit. But primarily you are protected because it’s the truth; the arrest may end up being harassment or erroneous but the arrest still occurred and thus, you are protected. Remember, the first element of libel is that it’s a false statement -- although the Texas Supreme Court has managed to muddy those waters.

Libel There is a fourth element that is often the most crucial when and if you ever enter a courtroom for a libel case – fault. Fault is a two-headed beast, and those heads are called actual malice and negligence. To determine the level of fault, a plaintiff’s status is evaluated to ascertain the burden of proof needed to win a judgment. • Public officials / public figures have to demonstrate that the falsehood was intentional, malicious or there was some deliberate violation of known protocols. • Private citizens have a less severe burden of proof -- they need only show that some degree of negligence is present in the information-gathering process

Libel In 1964, the Supreme Court ruled in Times v. Sullivan that defamation of a public official is permissible unless there is a reckless disregard for the truth. This is otherwise known as actual malice. So it’s OK to take out an ad saying Candidate A is a jerk for wanting to raise your taxes or the mayor’s towing program is stupid. In 1967, the court expanded its ruling to cover public figures as well.

Libel • A public officialis someone who has or appears to the public to have substantial responsibility for the conduct of government affairs. If they get paid by your tax dollars then they are a public official (includes police, elected officials, candidates etc.) • A public figureis a person with pervasive power or influence, or someone who thrusts themselves into the vortex of a public controversy. Texas courts have ruled that it makes no difference if they seek the spotlight or if the spotlight finds them. Includes activists, entertainers, athletes (so you can say what Randy Moss or Janet Jackson did was stupid). • A private citizen need only prove that there was negligence in the information gathering process.

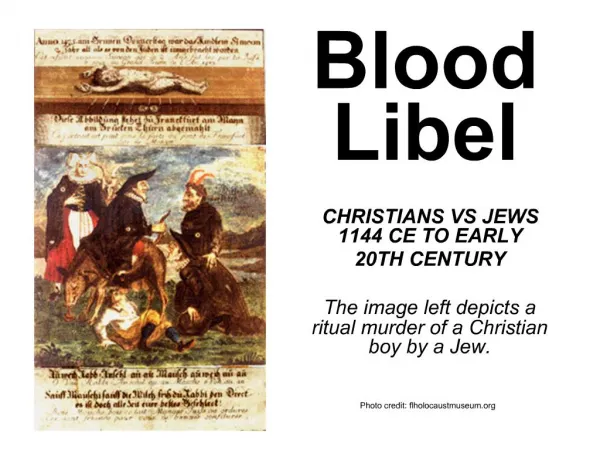

Libel per quod, libel per se When something is defamatory on its face – like calling someone a lying, Nazi, drug-dealing pedophile – that is called libel per se. It is the most common type courts deal with. But many states also recognize libel (or defamation) per quod. With the latter, the defamation is dependent upon the context and the interpretation of the listener/reader. For instance, it would be natural for a reader to presume that the bikers depicted in a photo accompanying a story about the Hell’s Angels are connected to that group. In both cases, the defamation must be false to be considered libelous.

Actual malice vs. negligence Texas courts have decided that the following is insufficient to be deemed actual malice: • The failure to perform further investigation or further interviews • Inconsistencies in internal policies, procedures etc. • Doing constant rewrites or omission of more favorable interviews • Evidence that the reporter hates the subject • Reporter is under continuous legal review

Libel danger areas • Shoddy or incomplete reporting. Not checking records thoroughly enough or misreading them. Not getting the other side of the story. • Photos -- using the wrong photo with a defamatory story. Using a photo out of context. • Quotes -- Tale bearers are just as guilty as tale tellers. Under the republication doctrine, if you print it, you own it. You are just as responsible for that quote as the person who said it. • Crime stories-- by definition they contain defamatory material. Be sure to use attribution. Avoid the use of the word “for” unless there is a conviction. (“Warrant for pastor in fur thefts; loot cached in organ at Park Falls” – pastor sued but didn’t win)

Libel danger areas: the “f-word” The word “for” is a three-letter word that will make you say a lot of four-letter words if it leads to a five-letter word – libel. Or a seven-letter word – lawsuit. They may be nuisance suits, but you have to pay a lawyer all the same. SafeNot safe Convicted for … Arrested for … Sentenced for … Charged for … Indicted for … On trial for … Allegedly for …

Libel defenses • Truth – Except Massachusetts? This is why accuracy is so important. You can make mistakes and live thanks to the doctrine of substantial truth: A defendant does not have to establish the literal truth of the publication in every detail as long as the "sting" or "gist" of the statement is substantially true. For example, you write a story that accuses the mayor of wasting $100,000 of the taxpayers’ money. The literal truth is that the amount was $50,000. The amount is wrong but the gist of the story is substantially true. • Privilege -- Covers any fair, true and impartial account of what goes on and what is said in court testimony, a public forum, a council meeting, the Senate etc. Covers any official meeting, judicial proceeding, executive or legislative proceeding • Fair comment – Libel is a misstatement of fact; there are no false opinions. Fair comment is the reasonable criticism of an official act • Consent -- That’s why photographers should have consent forms • Reply -- mostly in broadcast medium; a person such as a political candidate has the right to respond to criticism. No big deal now since FCC changed the rules.

How to stay out of court • Treat every story that could damage someone’s reputation like it’s fire. All facts should be confirmed and verified. Be consistent in your information gathering and reporting procedures. Beware of using unreliable sources. • Watch out for the so-called routine story -- they account for most libel cases • Be fair -- try to get the other side of the story. • Be careful with quotes -- Just because you tape-recorded it won’t save you. • If you make a mistake, but quick to run a correction. Demands for a retraction should go to your lawyer. Have a good corrections / retractions policy. • Take extra care with headlines and photo cutlines. Big type gets more attention than the little type.

Check the big type Since people will generally read the display type – headlines, cutlines, refers, teasers, art type – more often and more thoroughly, those elements require special care. Not that you can slack off in paragraph 57; it’s a simple fact that 48 point type will draw more eyes than 9 point type. In a 1998 lawsuit filed by famed O.J. houseguest Kato Kaelin against Globe Communications, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals held that a headline alone(“Cops think Kato did it”) can constitute libel.

Check the big type This was the lead story in the Baytown Sun on Jan. 15, 2008. Perhaps “Victim in serial attacks …” could work. Also note the smug look in the mug shot. The previous day’s headline was even worse -- "Baytown serial attacker begins trial today" … where was the copy editor?

How to stay out of court • Handle any phone calls from disgruntled folks with courtesy. • Have libel insurance and / or have good lawyers. Use lawyers on sensitive stories. • Try to stay up to date on changes in libel and privacy laws. • Notes -- keep ’em if you take good ones; pitch them if you take bad ones. Always tape police officials/officers on sensitive stories -- they will nearly always lie later. In Texas, there is one-party approval for taping. In general keep notes for a year – that is the statute of limitations on libel. • Using the word allegedly won’t save you -- look up “allege” in the AP stylebook. Use “alleged” or “suspected” or “accused” or “reputed” or similar phrases only when necessary to make clear that an unproved action is not being treated as fact. • Always use proper attribution -- saves you in libel and plagiarism.

Libel: More information For more information, please check out the “libel and privacy” section of the AP stylebook Also, the Reporters Committee on Freedom of the Press has a very useful Web site www.rcfp.orgthat provides a wealth of information on legal issues that apply to journalists, including: • State by state compilation of libel laws • How to fight a gag order • Court access and access to public records • How to use the FOI Act • Guidelines for photographers • Shield laws (Texas doesn’t have one; neither do feds and that‘s why Judith Miller of the NY Times is incarcerated.) Other good sources to help you stay apprised of legal issues are: www.poynter.org, magazines American Journalism Review and Columbia Journalism Review

Libel: Handouts, exercise • Libel write-arounds (some common libelous constructions and some Band-aids) • Libel primer • Red Flag words (page 177 of text), Dallas News story EXERCISE: • Find the libel in the Chronicle story, rewrite, do headline

Ethics An ethical decision-making toolbox

Ethics: What’s going on here? • In 1998, reporter Stephen Glass, right, was fired from the once-prestigious New Republic magazine for making up stories. • Boston Globe columnists Mike Barnicle and Patricia Smith were fired for making stuff up. Another Globe columnist was suspended for basing a column on an Internet hoax piece.

Ethics: What’s going on here? • In 1999, the Arizona Republic fired a columnist when the subjects of her columns could not be found. • The ABC Food Lion case, use of hidden cameras. Not a libel case; it was a fraud and trespass case. • Jayson Blair, right, was fired from the NY Times after his fabrications were outed by the San Antonio Express-News.

Ethics: What’s going on here? • USA Today fired Pulitzer nominee Jack Kelley, right, for embellishments and fabrications in his reporting. • A few years ago, CNN had to retract a story about the use of nerve gas in Vietnam. • The Cincinnati Enquirer paid $10 million to settle a potential lawsuit with Chiquita because of a series of stories that were based partly on stolen phone voice mail tapes.

Ethics: What’s going on here? • Columnists Armstrong Williams and Maggie Gallagher who had $240,000 and $21,500 contracts (that’s taxpayer money by the way) with the Education Dept. and HHS to write pro-Bush agenda material. • Sacramento Bee columnist Diana Griego Erwin, right, resigned in Sept. 2005 amid an investigation into whether she fabricated some of the people she mentioned in several columns. Erwin won a Pulitzer Prize and George Polk award while at the Denver Post in the 1980s.

Ethics: What’s going on here? CBS allowed Washington correspondent Rita Braver to do a profile on Lynne Cheney, the VP’s wife. Braver’s husband, lawyer Bob Barnett, had recently represented Lynne Cheney in getting a book published. Barnett was paid upfront, and so far CBS is defending Braver. Critics say Braver’s story will undoubtedly aid book sales. Any concerns here?

Ethics: Need for credibility Ethics and a strong sense of values form the cornerstone of credibility -- that C-word I will keep harping on all semester. Without credibility, few journalistic goals can be achieved. The true power of the media (including advertising and PR) lies in the ability to influence society through truth-telling. If the public can’t trust our product – information -- we won’t be very successful. In journalism, taking shortcuts is the path to danger.

Ethics: What’s going on here? And it’s not just the “other guys”: • The Conroe JP / grand jury story • The Kathy Whitmire / White House story • Chronicle columnist who borrowed a couple graphs from a Washington Post story • Chronicle food editor who plagiarized recipes • Former Chronicle editor who insisted Lebanese guerrillas be called “fighters,” made a one-graph reference to the accidental bombing of a Lebanese mental hospital by Israeli planes the play story, forbade AIDS stories and banned coverage of Houston’s Gay Pride Parade

Ethics: The ethics gap There is often a gulf of difference between how the news media view their profession/role and the public’s perception of the same – creating an “ethics gap,” if you will. This ethics gap can hurt credibility, and thus hamstring our communication goals. Newsmen might say that a doing a story about the lack of armor on military vehicles is at the heart of what defines journalism. But many in the public domain might consider the story muck-raking or unpatriotic to question the decisions of our leaders.

Ethics: The ethics gap Good illustration: The PBS program about ethics in the military and ethics in journalism: Military men said torture could be OK under some circumstances; Peter Jennings and Mike Wallace said that, in the need for objectivity, they wouldn’t intervene to reveal the position of enemy troops trying to ambush American soldiers.

The ethics gap: Contributing factors • The personal biases of the audience (“Why are you picking on my guy?”) • Lack of understanding of journalistic rules and goals (“Why give both sides?”) • Rise of “infotainment” has clouded news and soured public perceptions of the news media (“The Amber Frey / Natalee Holloway syndrome”) • Ivory tower attitudes by journalists. (“Our way of looking at things must be the right way.”) • Lack of news councils. No oversight body for journalists except in Minnesota and Washington state. • Sloppiness. Not doing your job. Realize that people will lie to you or spin the facts

Ethics: Guiding principles • Seek the truth and report it as fully as possible (afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted; give voice to the voiceless and hold the powerful accountable) • Act independently, avoiding associations that can create conflicts or cast doubt upon your information-providing goals • Minimize harm (to yourself, the medium your represent and to those directly and indirectly affected by the story)

Ethical decision-making Many stories will require you to make a variety of commonplace ethical decisions: the use of juvenile names, the use of a rape victim’s name, use of unnamed sources, whether to trust data in a report or survey, use of graphic photos. To best handle those sorts of situations, you need to create an ethical decision-making toolbox that is open- minded, fair and consistent. Readers/customers may not agree with your decision, but at least they will see it was the end result of a process – not whim.

Ethical decision-making • Gut reaction-- Listen to your gut but don’t always trust it. • Rule obedience-- Having rules helps with consistency, but beware of painting yourself into a corner with rules. • Reflection and reasoning-- Widens the circle of discussion in order to obtain additional viewpoints and create alternatives and options. Be careful about allowing one individual to provide a universal opinion. For instance, there is no universal black opinion or universal women’s opinion about most issues.

Ethical decision-making Relying on gut reaction and rule obedience for your decisions can be a quick fix, but those processes tend to give only “either / or” choices. Reflection and reasoning may be more time-consuming, but this approach provides more choices, which is the goal. After viewing the alternatives, you may end up deciding that your gut reaction was right or that the appropriate rule should be applied. But at least you have considered other choices that might be useful the next time your judgment is called for and the facts are slightly different.

Ethical decision-making: The process • Take note of what newsroom rules apply. • Invite collaboration. Collaboration thrives in an environment where input is not only allowed, but valued equally. • Consider the consequences of any course of action OR inaction. What will the possible results or counteractions be? • Determine who the stakeholders are. Who will be most affected by your decision? The stakeholders could include the journalist, the subject, relatives / friends of the subject or the news organization itself. • Decide what principles, both as a human and as a journalist, need to be applied. • Try to reach a consensus or present alternatives that allow you to accomplish your journalistic goals while minimizing harm. See the list of questions on Page 4 of the handout.

Ethical decision-making Class exercise: After being missing a year, Utah teenager Elizabeth Smart is found. Her two abductors are arrested. A day after the initial “reunion” story, you learn that Smart was sexually abused. Your shop has a rule against naming rape victims. What do you do?

Ethics: class exercise This is one of the most famous images from the war in Iraq and is one of many photos released depicting the treatment of detainees at Abu Ghraib prison. What are your journalistic obligations? Would you run it? Where would you run it? Does it hurt our troops / political leaders? Does the latter impact your decision?

Ethics: Some don’ts • Don’t stage events -- The NBC / exploding Chevy truck story. Producer didn’t realize that what he did would not only damage his credibility but that of the entire TV news medium as well. Photogs with throw-down kids’ toys and shoes. • Don’t ask someone to do something that otherwise would not have happened -- be careful of protests. If you ask what time a demonstration will be held, and the organizer replies “what time do you want it to be?” then hang up. • Don’t put anything on the air or in print that can’t stand up to scrutiny -- If the mechanics of information-gathering are questionable, then the story’s credibility will suffer. ABC Food Lion case, CBS and the Bush story

Ethics: In conclusion … Doing your job in a professional and ethical manner will boost your credibility and enhance your marketability. Folks might disagree with your decision or not like a particular story, but at least they will know your information can be trusted. Also, realize that as a human being, you can never be fully objective. But you can strive to be fair and be consistent in that fairness.

Exercise: The Somalia photo During the Oct. 1993 battle in Mogadishu, Somalia, 18 U.S. soldiers were killed during an operation. Among the dead were two helicopter pilots whose bodies were dragged through the street (the famed Black Hawk Down incident). One Somali is making an obscene gesture. There is not much blood on the body, and the pilot may or may not be recognizable. This photo, shot by Paul Watson of the Toronto Star, was shown on TV news networks throughout the day.

Exercise: The Somalia photo • Now it is time for you to decide what to do with the photo. You are the editor of a midsize daily newspaper in the Houston area; that is your audience. Your general rule is to avoid publishing photos of dead bodies. • Work individually or in collaboration with classmates or others. Seek additional information from the Web or other sources. • Try to answer as many of the 10 questions in the reflection and reasoning process that apply. • Write down what your decision is regarding the photo (a page?). Explain how you came up with that decision and how you would defend it when the phone starts ringing. • This is a must extra-credit exercise. It is worth a letter grade boost to a story assignment or a step-grade reduction if not done.