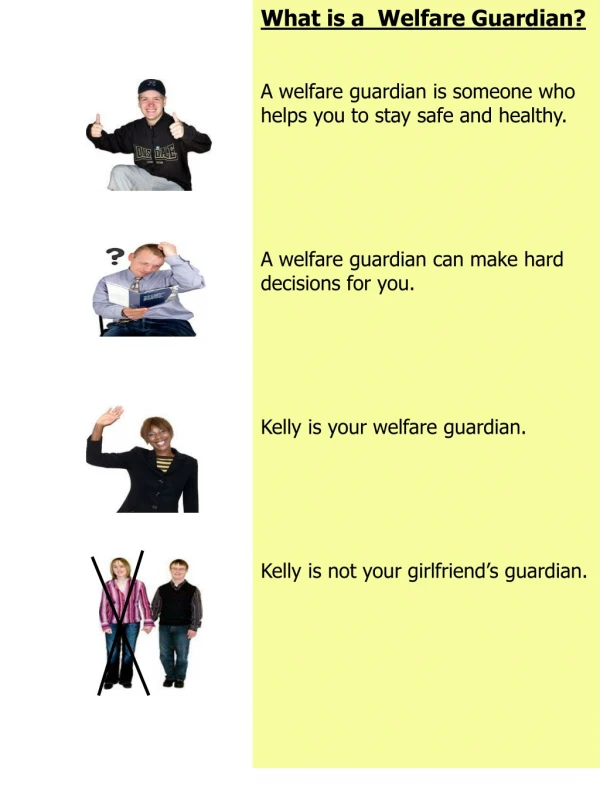

Welfare Guardian

330 likes | 490 Vues

Welfare Guardian. Welcome, While we wait for others to join: 1. Click on the telephone icon in the app 2. Click on "Call via internet" 3. Click on "Connect" 4. Adjust your volume. Welfare Guardian. Responding to Self-harm in Schools Dr Erin Bowe Clinical Psychologist. Nomenclature.

Welfare Guardian

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Welfare Guardian Welcome, While we wait for others to join: 1. Click on the telephone icon in the app 2. Click on "Call via internet" 3. Click on "Connect" 4. Adjust your volume

Welfare Guardian Responding to Self-harm in Schools Dr Erin Bowe Clinical Psychologist

Nomenclature Current and preferred term is ‘nonsuicidal self-injury’ (NSSI) ‘self-harm’ or ‘self-injury’ is easier for everyday speak Regional differences in terms Self-poisoning has different motivations & lethality

Introduction: Goals of session To better equip yourself and staff to deal with common incidents To improve skills in determining appropriate level of response for a range of possible crisis events To learn tricks in using principles of calm, factual and non-emotive language To have a clearer understanding of how to seek further advice and support for yourself, staff, students and parents

Overview Understanding self-harm behaviours Responding to crisis Communication skills Special considerations within school settings Self-care, supervision and referral

Pre and post-workshop reflection 0= NOT AT ALL CONFIDENT 1= SOMEWHAT CONFIDENT 2= CONFIDENT How confident do you feel: Working with students who have engaged in self-harm? Being able to differentiate a crisis from more intermediate and mild incidents? Understanding best-practice treatment approaches for self-harm? That you could handle a crisis?

Self-harm is Deliberate cutting, burning, scratching with the intent of causing bodily tissue For the purpose of affect regulation (to feel ‘better’, ‘calmer’ or just ‘different’) Almost always non-suicidal Usually repetitious Usually associated with powerful, rewarding psychophysiological responses A maladaptive, but effective coping strategy

Self-harm in this context is not to be confused with: A suicide attempt Parasuicide (behaviour which mimics suicide attempt) (Sub)culturally accepted body modification Stereotypic/compulsive self-harm (neurological basis) Psychotic self-harm (e.g., self-amputations) Indirect or cumulative bodily damage (eating disorder, substance use, or risky stunts)

Predisposing factors Stressful events Self-harm specific factors Self-harm outcome Cognitive-emotional-biological vulnerability • High emotion reactivity • Emotional numbing • Poor distress tolerance • Thought suppression • Rumination • Stressful event Triggers over or under Arousal (automatic Functions) OR • Event presents high Social demands (Social function) Social vulnerability • Early abuse/maltreatment • Familial hostility/criticism • Poor communication skills • Poor problem solving x + = Regulation of emotional experience • High self-criticism • Modelling of peers/media • Need for strong/honest signal Self-harm Regulation of social situation Psychological model of the development and maintenance of self-harm (Nock & Cha, 2009)

Who does it? Appears to be 3 possible pathways ‘One-off’, non-rewarding response (about 30%) Tension reduction* response (about 70% will repeat) Atypical, excitation** response (seen in Borderline PD; or a least a subtype of BPD, unknown % but likely very low) *Well established in literature **Less well established in literature, still speculative

‘Typical’ response: tension reduction model Increased levels of negative emotions Depersonalisation occurs Individual reaches a level they are no longer able to tolerate Engage in act of self-harm with little/no pain (injury opens access to the brain’s 24 hour pharmacy of endorphins & opiates) Repersonalisation occurs (negative reinforcing property)

Typical response Poor coping skills Low tolerance for negative emotions Impulsive, want instant relief Perceived lack of control High levels of dissociation Often unable to utilise problem solving once distress reaches a certain threshold

Typical response • Experience interpersonal conflict, rejection, separation, anger, self-hatred, depression, loneliness and abandonment • Experiences may be real or imagined • As self-harm become habitual, cutting is often precipitated by more minor events

Faulty Assumptions- “why?” • Most people have a hard time explaining “why” they cut (content) • But can describe what, where, how led to the behaviour (process) • Does the “why?” change anything? • Fundamentally, self-harm is a maladaptive coping strategy • It’s an attempt to communicate distress • Counsellors should try to prioritize process over content

Crisis #1 You or another student finds someone cutting in private (e.g., in bathroom) Respond neutrally & model calm posture (think: relax jaw, relax hands, relax shoulders) Offer support (get band aids, offer a chance to talk about it) without being reactive Use empathic statements, focus on immediacy

Crisis #1 continued 4. Immediacy- ask the student what s/he wants to happen next an offer 2-3 options. 5. Follow up. Book a time to talk, or talk to the student about referral. 6. Reflect on your own self-care & debriefing needs

Crisis #2 A student or students engage in self-harm in front of others (e.g., in class) Use empathic reminders that (1) it’s ok to be upset, but (2) others are upset by the behaviour. Offer support (bandaids, a chat) Offer 2-3 options: 1. clean up & go back to class, 2. Sit somewhere quiet with a friend until next class, or 3. visit counsellor/debrief with someone

Crisis #2 continued 4. Manage any other students’ distress by acknowledging & validating, but quickly moving forward (give the same options – break, talk, or resume class) 5. Follow up. Book a time to talk, or talk to the student about referral. 6. Reflect on your own self-care & debriefing needs.

Non-immediate crisis A student reveals that s/he has engaged in self-harm (but no current crisis) Simply ask the student what s/he wants to have happen now (talk now, or later?) Make sure a follow up time is booked (preferably by the end of the day) Aim to clarify the intent (“so the cutting was about feeling overwhelmed, but not about taking your life?”)

Non-immediate crisis cont. 4. Encourage parental communication (consider age and mature minor principle if necessary) 5. Encourage a referral to an external psychologist (particularly important if the student is not open to parental disclosure)

Send students home? No, not unless absolutely necessary Tends to reinforce the behaviour Increases feelings of rejection & isolation

Self-harm in groups & cliques Represents a unique but not unusual occurrence in ‘institutional’ settings (schools, hospitals, prisons) Contagion effect Important to correct any misinformation and address ‘us vs. them’ phenomena Work towards strengthening alliance between parents, adolescents and counsellor

Addressing the Issue: Groups? Can be effective if student has a circle of non self-harming friends Similarly, older students who have recovered are a strong source of modelling and support Groups with only people who self-harm need to be selected very carefully, they need to be highly structured and run by an experienced therapist

Risks with Groups False assumption that all members want to change; or that the motivation for change is stable/consistent Participant matching issues in school setting Members can often provide false validation rather than support Extra challenges with personality disorder, trauma, eating disorder and substance use Risk of re-triggering & re-traumatisation Risk of ‘one-upmanship’ behaviours Biased motivations for participating ‘sharing’ not as effective as structured skill-based groups

Communication skills Immediacy Neutral tone of voice, face and statements Importance of orienting the student to counselling process Try to avoid the temptation to get into lengthy discussions with students or parents about “why” people self-harm Teach/model skills in emotion identification, labelling and explaining Focus on the factual information about the mechanics or the process (i.e., reduces heart rate, body releases natural feel-good opioid hormones)

Realistic options for school counselling Crisis management, putting out ‘spot fires’ Educating others, translating knowledge Explain behaviour curve- delay, distract, decide Ongoing motivational interviewing Encourage replacement skills early on, but acknowledge their limited use & use as a tool for encouraging long-term strategies

Road blocks to student care • Anxiety is the biggest block to care • Listening your own thoughts, rather than the students • Can’t be present and calm if you’re rehearsing • Questioning like a lawyer rather than an anthropologist • When you’re working harder than the client • Being impatient or intolerant of silence • Mismatching your approach to client’s actual stage of readiness to change

Referring out If ever in doubt, refer out Most self-harm takes 12 mo+ to treat effectively Emphasise confidentiality Validate ambivalence about seeking help & keep encouraging Achievable goal in short-term for most students is (1) waiting skills and (2) reducing frequency (rather than cessation)

Worksheets and Handouts Responding to Crisis flowchart Basic Distraction Techniques Handout for Parents Quick Facts about self-harm Tips and strategies for adolescents Tips and strategies for younger children

Summary Self-harm is almost always non-suicidal Maladaptive but effective coping strategy Is a way of communicating distress The psychophysiology of self-harm is very powerful Is incredibly difficult to treat. Follows similar patterns to other addictive behaviours Addressing motivation to change is crucial first step It must be the individual’s choice to stop, you cannot make someone stop

Summary Familiarise self with facts, practice neutral communication Differentiate immediate crisis from more mild or intermediate events Consider how to make transition from self-harm incident back to regular activities more seamless Consider how to tackle cliques (talk to each member one on one to reduce contagion) Remember to reflect and address own self-care

Post-workshop reflection 0= NOT AT ALL CONFIDENT 1= SOMEWHAT CONFIDENT 2= CONFIDENT How confident do you feel: • Working with students who have engaged in self-harm? • Being able to differentiate a crisis from more intermediate and mild incidents? • Understanding best-practice treatment approaches for self-harm? • That you could handle a crisis?

Supervision This time of year is usually the beginning of ‘peak’ self-harm trends in schools Do you need further support, coaching or guidance about how to manage self-harm in schools? Just need someone external to school to bounce ideas off? Individual supervision via Skype or at our Port Melbourne office is available