Enhancing IDU Health: Mapping Local Influences in Polish City

10 likes | 117 Vues

Explore the Rapid Policy Assessment and Response (RPAR) process conducted in Szczecin, Poland, to improve well-being of injection drug users through local cooperation and action planning based on a thorough power map analysis.

Enhancing IDU Health: Mapping Local Influences in Polish City

E N D

Presentation Transcript

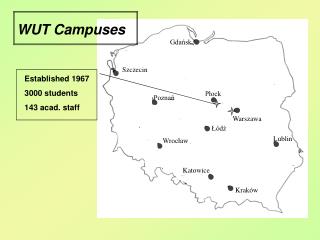

The Szczecin Nat ’ l National Office AIDS Power Map for Center Counteracting Nat ’ l Drug MOH Addiction City Prison Government Return Defense from U lawyers Judges MONAR TADA Prosecutors Methadone clinic Psychologists RPAR Police Church Detox Interagency Infectious program Alcohol Diseases committee Clinic Media Social Business outpatient aid Medical clinic rescue The Governance of Care: Mapping Local Influences on IDU Health Interventions in a Polish City Sobeyko J (1)(8), Leszczyszyn-Pynka M (1)(2), Duklas T (7), Parczewski M (1)(2), Bejnarowicz P (1), Chintalova-Dallas R (5), Lazzarini Z (4)(6), Case P (5), Burris S (3)(6). The RPAR Rapid Policy Assessment and Response (RPAR) is a community-level action research intervention process. An RPAR was conducted in Szczecin, Western Pomerania Province, Poland from January-October 2005. The aim of the RPAR was to diagnose the drug policy problems in the region and, working with a diverse Community Action Board (CAB), to create an Action Plan to improve the well-being of injection drug users in the region. Rapid Policy Assessment and Response is an action research method in which local researchers guided by a Community Action Board (CAB) collect and analyze laws, epidemiological and criminal justice statistics, and data from focus groups and key informant interviews to learn how the law, policies and their implementation influence health risks among IDUs. Analytic tools included a “power map” depicting the institutions that play important direct or indirect roles in shaping and implementing policies and how these institutions interact. The ultimate goal of RPAR is to stimulate local cooperation to reduce environmental risks to IDU. The RPAR was conducted in Szczecin between January and October, 2005, a final report was released in March, 2006. The CAB included representatives of law enforcement (the police, judiciary, prisons), both public and private drug treatment providers, health care (physicians, nurses) and social welfare agencies (Family Support office). Existing laws and formal policies in ten domains relevant to drug policy and health (including harm reduction, drug treatment and prevention) were collected. To determine how these laws were being put into practice, three focus groups were conducted, and the team interviewed 24 people in law enforcement, health care and social services, as well as 14 IDUs. Outcomes and Lessons Learned The Szczecin power map showed a diversity of government agencies and NGOs influencing the risk environment for IDUs. We reflected upon the factors that allow interventions aimed at drug users, including the RPAR, to go forward with a reasonable degree of success: • Local harm reduction and drug treatment agencies are well established in law and practice. • National legislation clearly authorizes both syringe exchange and methadone maintenance treatment. • Polish drug demand policy is decentralized and it is municipal task to implement local drug policy, which means that the city government of Szczecin directly funds a number of NGOs and programs, giving them immediate local legitimacy and a voice in policy. • The RPAR was endorsed by the city government, which provided a meeting facility for the CAB in the City Hall • In both law and daily practice, the police did not have a monopoly on governance of drug issues. • On paper, harm reduction and treatment are official national policy with the same validity as drug control policies. • In practice, health, drug treatment and harm reduction agencies have the status and resources necessary to balance the law enforcement approach to drug issues. • Public health and harm reduction agencies have a voice in city politics, and physicians caring for people with HIV have provided training for police on AIDS/STI and drug issues. • The prohibitionist aspects of Polish drug policy have not de-legitimized public health approaches. • In spite of prohibitions legislation in the late 1990s, Polish law has continued to promote treatment instead of incarceration. • Police, prosecutors and courts have generally not been putting people into prison for possession of small amounts of drugs. • Drug users are seen as deserving of social assistance. • Cost-effective health interventions like methadone and syringe exchange have been implemented, at least in major cities. The National AIDS Center provides funding for TADA and other local prevention projects, and data and technical assistance to RPAR RPAR brought together NGOs (e.g. MONAR, TADA), health and social service providers and law enforcement to address policy barriers to IDU health The municipal“blessed” the RPAR, helped recruit CAB and provided a place to meet in City Hall When SEP was first introduced, national authorities instituted training for law enforcement Participated in CAB and/or focus group interviews; worked with RPAR to develop training scheme Return from U [Addiction] supports families of people with drug addiction. It has had long term government funding, and was represented on RPAR CAB MONAR is the oldest Polish NGO providing treatment, social support and harm reduction services to IDUs. It has been funded for many years by national and local government Police leaders participated on CAB Police officers provide drug abuse training in schools TADA was founded in 1995 to prevent HIV/STDs among Szczecin sex workers. After RPAR it leads a network of agencies serving drug users and their families, funded by national Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs The Szczecin Methadone Clinic began service in the late 1990s. It has 70 clients and close connections with AIDS treatment system This research was supported by NIDA/NIH Grant # 5 R01 DA17002-02 PI: LAZZARINI, ZITA . The findings and conclusions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of NIH, NIDA, or the US Government. The development of RPAR was supported by the International Harm Reduction Development Program of the Open Society Institute in 2001-2002. (1) Infectious Disease Prevention and Public Health Promotion Association AVICENNA, (2) Department of Infectious Diseases & Hepatology, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, (3) Temple University Beasley School of Law, (4) University of Connecticut Health Center, (5) Fenway Community Health Center, (6) Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities, (7) Association for Health Promotion and Social Risks Prevention “TADA”; (8) Independent Laboratory of Family Nursing, Pomeranian Medical University