STORY TELLING

390 likes | 817 Vues

This article explores the transformative role of storytelling in business, drawing insights from Stephen Denning's "Telling Tales," Jim Collins' "Good to Great," and Akio Morita's "Made in Japan." It discusses how storytelling can convey complex ideas and inspire action, contrasting traditional analysis with engaging narratives. Through examples like Denning's story about a health worker in Zambia, the article illustrates how effective storytelling captivates audiences and motivates them to embrace change. Learn how well-crafted stories in a corporate context can drive engagement and innovations.

STORY TELLING

E N D

Presentation Transcript

STORY TELLING Based on the article by “Telling Tales” Stephen Denning, Harvard Business Review, May 2004 Also draws heavily from “Good to Great” by Jim Collins, and “Made in Japan” by Akio Morita

INTRODUCTION • In the mid-1990s, the goal was to get people at the World Bank to support efforts at knowledge management. • Steve Denning had strong arguments for bringing together the knowledge that was scattered throughout the organization. • He made PowerPoint presentations that emphasised the importance of sharing and leveraging this information. • But with little effect • In 1996, Denning began telling people a story.

THE STORY OF ZAMBIA • In June of 1995, a health worker in a tiny town in Zambia went to the Web site of the Centres for Disease Control and got the answer to a question about the treatment for malaria. • Zambia is one of the poorest countries in the world, and it happened in a tiny place 600 kilometres from the capital city. • But the most striking thing about this picture, was that the World Bank wasn't in it. • Despite its know-how on all kinds of poverty-related issues, that knowledge was not available to the millions of people who could use it. • This simple story helped World Bank staff and managers envision a different kind of future for the organization.

At the International Storytelling Centre, Denning told the Zambia story to a professional storyteller. The feedback? There was no real telling. There was no plot. There was no building up of the characters.

Who was this health worker in Zambia? • And what was her world like? • What did it feel like to be in the exotic environment of Zambia, facing the problems she faced? • The anecdote was not a story at all. Denning needed to start from scratch to turn it into a "real story."

DO STORIES REALLY HAVE A ROLE TO PLAY IN THE BUSINESS WORLD? • Analysis is what drives business thinking. It cuts through myth, gossip, and speculation to get to the hard facts. • Its strength lies in its objectivity, its impersonality, its heartlessness. • Yet this strength is also a weakness. Analysis might excite the mind, but it hardly offers a route to the heart. • A route to the heart is needed to motivate people not only to take action but to do so with energy and enthusiasm.

Leadership involves inspiring people to act in unfamiliar, and often unwelcome, ways. • Numbers or PowerPoint slides won't achieve this goal. • But effective storytelling often does. In fact, in certain situations nothing else works. • Although good business arguments are developed through the use of numbers, they are typically approved on the basis of a story--that is, a narrative that links a set of events in some kind of causal sequence. • Storytelling can translate those dry and abstract numbers into compelling pictures of a leader's goals

WHAT IS A GOOD STORY? • A story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. • It should include complex characters as well as a plot that incorporates a reversal of fortune and a lesson learned. • The storyteller should be so engaged with the story--visualizing the action, feeling what the characters feel that the listeners become drawn into the narrative's world.

LESSONS FROM STORIES Go through the following stories and try to draw a lesson from each of them.

IBM • At an IBM manufacturing site stories circulated among the blue-collar workers about the facility's managers, who were accused of "not doing any real work," "being overpaid," and "having no idea what it's like on the manufacturing line." • One day, a new site director turned up in a white coat, unannounced and unaccompanied, and sat on the line making ThinkPads. He asked workers on the assembly line for help. In response, someone asked him, "Why do you earn so much more than I do?" His simple reply: "If you screw up badly, you lose your job. If I screw up badly, 3,000 people lose their jobs." • While not a story in the traditional sense, the manager's words--and actions--served as a seed for the story that helped counter the perception about managers' being lazy and overpaid. The atmosphere at the facility began improving within weeks.

CIRCUIT CITY • In 1973, one year after he became CEO, Alan Wurtzel’s company stood at the brink of bankruptcy. At the time, the company was a hodgepodge of appliance and hi-fi stores with no unifying concept. Over the next ten years, Wurtzel and his team not only turned the company around, but also created the Circuit City concept and laid the foundations for a stunning record of results. • When Alan Wurtzel started the long turnaround, he began with the question of where to take the company Wurtzel resisted the urge to walk in with the answer. Instead, he began not with answers, but with questions. Wurtzel stands as one of the few CEOs in a large corporation who put more questions to his board members than they put to him. • He used the same approach with his executive team, constantly pushing and probing and prodding with questions. Each step along the way, Wurtzel would keep asking questions until he had a clear picture of reality and its implications. “They used to call me the prosecutor, because I would home in on a question,” said Wurtzel. “You know, like a bulldog, I wouldn’t let go until I understood. Why, why, why? • Adapted from “Good to Great” by Jim Collins.

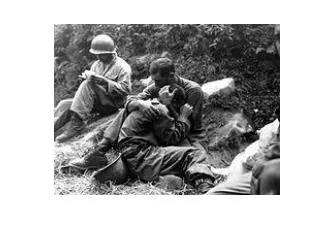

THE STOCKDALE PARADOX • Admiral Jim Stockdale, was the highest ranking United States military officer in the “Hanoi Hilton” prisoner-of-war camb during the height of the Vietnam War. He was tortured over twenty times during his eight-year imprisonment from 1965 to 1973. He shouldered the burden of command, doing everything he could to create conditions that would increase the number of prisoners who would survive unbroken, while fighting an internal war against his captors and their attempts to use the prisoners for propaganda. At one point, he beat himself with a stool and cut himself with a razor, deliberately disfiguring himself, so that he could not be put on videotape as an example of a “well-treated prisoner.” He exchanged secret intelligence information with his wife through their letters, knowing that discovery would mean more torture and perhaps death. He instituted rules that would help people to deal with torture. He instituted an elaborate internal communications systems to reduce the sense of isolation that their captors tried to create, which used a five-by-five matrix of tap codes for alpha characters. Once the prisoners mopped and swept the central yard using the code, swish-swashing out “We love you” to Stockdale.

Jim Collins eagerly looked forward to the prospect of spending an afternoon with Stockdale. As they got talking, Stockdale remarked, “I never lost faith in the end of the story, I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which, in retrospect, I would not trade.” • After a period of silence, Collins asked, “Who didn’t make it out?” • “Oh, that’s easy,” he said, “The optimists.” Collins was completely confused. • Stockdale explained, “The optimists, Oh, they were the ones who said, “We’re going to be out by Christmas.” And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.” • Adapted from “Good to Great” by Jim Collins.

THE HEDGEHOG AND THE FOX • In his famous essay, “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” Isaiah Berlin divided the world into hedgehogs and foxes, based upon an ancient Greek parable. The fox, a cunning creature, can devise several complex strategies for sneak attacks upon the hedgehog. Day in and day out, the fox circles, around the hedgehog’s den, waiting for the perfect moment to pounce. Fast, sleek, and crafty – the fox looks like the sure winner. The hedgehog, on the other hand, waddles along, searching for lunch and taking care of his home. • Minding his own business, the hedgehog wanders right into the path of the fox. “Aha, I’ve got your now!” thinks the fox,. He leaps out, bounding across the ground, lightning fast. The little hedgehog, sensing danger, looks up and thinks, “Here we go again. Will he ever learn?” Rolling up into a perfect little ball the hedgehog becomes a sphere of sharp spikes, pointing outward in all directions. The fox bounding toward his prey, sees the hedgehog defense and calls off the attack. Retreating back to the forest, the fox begins to calculate a new line of attack. Each day, some version of this battle between the hedgehogs and the fox takes place, and despite the greater cunning of the fox, the hedgehog always wins. • Adapted from “Good to Great” by Jim Collins.

THE BOEING 707 • Until the early 1950s, Boeing focused on building huge flying machines for the military. However, Boeing had virtually no presence in the commercial aircraft market. McDonnell Douglas had vastly superior abilities in the smaller, propeller-driven planes that composed the commercial fleet. • In the early 1950s, however, Boeing saw an opportunity to leapfrog McDonnell Douglas by marrying its experience with large aircraft to its understanding of jet engines. • Led by Bill Allen, Boeing executives debated the wisdom of moving into the commercial sphere. They came to understand that, whereas Boeing could not have been the best commercial plane market a decade earlier, the cumulative experience in jets and big planes they had gained from military contracts now made such a dream possible.

They also came to see that the economics of commercial aircraft would be vastly superior to the military market and they were just flat-out turned on by the whole idea of building a commercial jet. • So, in 1952 Allen and his team made the decision to spend a quarter of the company’s entire net worth to build a prototype jet that could be used for commercial aviation. They built the 707 and launched Boeing on a bid to become the leading commercial aviation company in the world. Three decades later, after producing five of the most successful commercial jets in history (the 707, 727, 737, 747, 757), Boeing stood as the greatest company in the commercial airplane industry, worldwide. • Adapted from “Good to Great” by Jim Collins.

SONY’S TRANSISTOR RADIO • Sony’s first transistor radio of 1955 was small and practical – Morita saw the United States as a natural market; business was booming, employment was high, the people were progressive and eager for new things, and international travel was becoming easier. • Morita took his little $29.95 radio to New York and made the rounds of possible retailers. Many of them were unimpressed. They said, “Why are you making such a tiny radio? Everybody in America wants big radios. We have big houses, plenty of room. Who needs these tiny things?” • The fidelity was not as good as a large unit, but it was excellent for its size. Many people saw the logic of this argument, and Morita was happy to be offered some tempting deals. • The following is Morita’s narrative: “The people at Bulova liked the radio very much and their purchasing officer said very casually, “We definitely want some of these. We will take one hundred thousand units.” One hundred thousand units! I was stunned. It was an incredible order, worth several times the total capital of our company. We began to talk details, my mind working very fast, when he told me that there was one condition: we would have to put the Bulova name on the radios .

I told him I would check with my company, and in fact I did send a message back to Tokyo outlining the deal. The reply was, “Take the order.” I didn’t like the idea, and I didn’t like the reply. After thinking it over and over, I decided I had to say no, we would not produce radios under another name. When I returned to call on the man from Bulova he didn’t seem to take me seriously at first. How could I turn down such an order? He was convinced I would accept. When I would not budge, he got short with me. • “Our company name is a famous brand name that has taken over fifty years to establish,” he said. “Nobody has ever heard of your brand name. Why not take advantage of ours?” • “Fifty years ago,” I said, “your brand name must have been just as unknown as our name is today. I am here with a new product, and I am now taking the first step for the next fifty years of my company. Fifty years from now I promise you that our name will be just as famous as your company name is today.” • Adapted from “Made in Japan,” by Akio Morita

SONY RADIO • While making the rounds Morita came across an American buyer who looked at the radio and said he liked it very much. He said his chain had about 150 stores and he would need large quantities. That pleased Morita, and fortunately he did not ask Morita to put the chain’s name on the product. He only wanted a price quotation on quantities of 5000, then 10,000, 30,000, 50,000 and 100,000 radios. Morita was thrilled! But back in his hotel room, he began pondering the possible impact of such grand orders on the small facilities in Tokyo. Sony had expanded its plant a lot since outgrowing the unpainted, leaky shack on Gotenyama. Sony had moved into bigger, sturdier buildings adjacent to the original site and had its eye on some more property. But Morita did not have the capacity to produce 100,000 transistor radios a year and also make the other things in Sony’s small product line. Sony’s capacity was less than10,000 radios a month. If the company got an order for 100,000 it would have to hire and train new employees and expand its facilities even more. This would mean a major investment, a major expansion, and a gamble.

The following is Morita’s account: “I was inexperienced and still a little naive, but I had my wits about me. I considered all the consequences I could think of, and then I sat down and drew a curve that looked something like lopsided letter U.” • The price for 5000 would be our regular price. That would be the beginning of the curve. For 10,000 there would be a discount, and that was at the bottom of the curve. For 30,000 the price would begin to climb. For fifty thousand the price would begin to climb. For 50,000 the price per unit would be higher than for 5000 and for 100,000 units the price would have to be much more per unit than for the first 50000.

He mentioned: “I know this sounds strange, but my reasoning was that if we had to double our production capacity to complete an order for one hundred thousand and if we could not get a repeat order the following year we would be in big trouble, perhaps bankrupt, because how could we employ all the added staff and pay for all the new and unused facilities in the case? It was a conservative and cautious approach, but I was convinced that if we took a huge order we should make enough profit on it to pay for the new facilities during the life of the order. Expanding is not such a simple thing – getting fresh money would be difficult – and I didn’t think this kind of expansion was a good idea on the strength of one order. In Japan we cannot just hire people and fire them whenever our orders go up or down. We have a long-term commitment to our employees and they have a commitment to us.” • Adapted from “Made in Japan,” by Akio Morita

ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE • Hewlett Packard Broke a lock on a closed door Wanted people to have free access • Tom Watson A salesman made a huge mistake Watson remarked that the millions of dollars had gone into educating the person.

CHOOSING A STORY Different occasions demand different stories.

IF YOUR OBJECTIVE IS: Sparking action • You will need a story that describes how a successful change was implemented in the past, but allows listeners to imagine how it might work in their situation. • In telling it, you will need to avoid excessive detail that will take the audience's mind off its own challenge. • Your story will inspire such responses as "Just imagine…" "What if…"

IF YOUR OBJECTIVE IS : Communicating who you are • You will need a story that provides an engaging drama and reveals some strength or vulnerability from your past. • Include meaningful details, but also make sure the audience has the time and inclination to hear your story. • The responses should be: "I didn't know that about him!" "Now I see what she's driving at."

IF YOUR OBJECTIVE IS : Transmitting values • You need a story that feels familiar to the audience and will trigger discussion about the issues raised by the value being promoted. • Use believable (though perhaps hypothetical) characters and situations, and never forget that the story must be consistent with your own actions. • The responses may be "That's so right!" "Why don't we do that all the time?"

IF YOUR OBJECTIVE IS : Fostering collaboration • You will need a story that movingly recounts a situation that listeners have also experienced and that prompts them to share their own stories about the topic. • Keep the discussion spontaneous and ensure an action plan is ready to tap the energy unleashed by this narrative chain reaction. • The responses may be : "That reminds me of the time that I…" "Hey, I've got a story like that."

IF YOUR OBJECTIVE IS : Taming the grapevine • You will need a story that highlights, often through the use of gentle humour, some aspect of a rumour that reveals it to be untrue or unlikely. • Avoid the temptation to be mean-spirited, and be sure that the rumour is indeed false. • The responses may be : "No kidding!" "I'd never thought about it like that before!"

IF YOUR OBJECTIVE IS : Sharing knowledge • You need a story that focuses on mistakes made and shows in some detail how they were corrected, with an explanation of why the solution worked. • Solicit alternative and possibly better solutions. • The responses could be "There but for the grace of God…" "Wow! We'd better watch that from now on."

IF YOUR OBJECTIVE IS : Leading people into the future • You need a story that evokes the future you want to create without providing excessive detail that will only turn out to be wrong. • Be sure of your storytelling skills. • Otherwise, use a story in which the past can serve as a springboard to the future. • The expected responses are : "When do we start?“ or "Let's do it!"