Private Security Actors

570 likes | 1.13k Vues

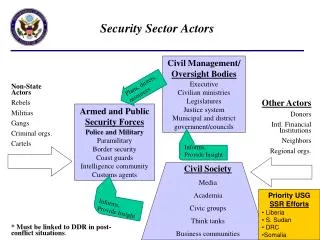

Private Security Actors. Private Security Companies Defense Producers Private Military Companies Non-statutory forces Mercenaries. Private Security Companies. Guarding Sector Protection & surveillance Guarding factories, mines, shopping malls, etc

Private Security Actors

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Private Security Actors Private Security Companies Defense Producers Private Military Companies Non-statutory forces Mercenaries

Private Security Companies Guarding Sector • Protection & surveillance • Guarding factories, mines, shopping malls, etc • Neighborhood patrol & “gated communities” • Law & order in public places Security & surveillance Sector • Installing and operating alarms, access control, protection, and quick reaction devices • Anti- & countersurveillance, undercover observ • Sweeping and intrusion detection services

Private Security Companies Investigation & risk management Sector • Investigations: matrimonial disputes, labor matters, vetting, witness services, supermarket slip-ups, insurance and other fraud, etc • Private and industrial espionage, intelligence collection, and counterintelligence • Risk management consulting Crime prevention & correcting Sector • Kidnap and blackmail response • Prevention and detection of criminals and other wrongdoers • Management of prisons and prisoner transport

Private Security Companies Not defined in international law A registered civilian company that, for profit, specializes in providing contract commercial services to domestic and foreign entities with the intent to protect personnel and humanitarian and industrial assets within the rule of applicable domestic law

Defense Producers Weapons Production • R&D • Production • Maintenance & repairs Military Assistance • Military & weapons training • Information Warfare and PSYOPs • Export of weapons, equipment and components

Private Military Companies Consulting • Threat analysis, strategy development, advice • Restructuring of Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics and Support • Logistics in emergencies, war and conflict • Mine clearing, refugee camps, infrastructure, demobilization & reintegration • Management of military bases, transports Technical Services, Maintenance and Repairs • Tech services, air control, intelligence, IT services • Weapons maintenance and repair

Private Military Companies Training • Military, weapons, Special Forces, languages, Information warfare and PSYOPs training Peacekeeping and Humanitarian Assistance • Logistics for peacekeeping • Disarmament, mine demining, explosive disposal, weapons collection and destruction • Protection of convoys, refugees, humanitarian aid organizations, and VIPs Combat Forces

Private Military Companies Not defined in international law A registered civilian company that, for a profit, specializes in the provision of contract military training (instruction and simulation programs), military support operations (logistic support), operational capabilities (special forces advisors, C4IRS) and/or military equipment to legitimate domestic and foreign entities

MPRI Areas where MPRI provides outstanding capabilities include, but are not limited to: • Training and Education • Professional Development Programs • Programming, Budgeting, and Strategic Planning • War Gaming, Modeling and Operation of Simulation Centers • Development and Operation of Combat Training Centers • Corporate Staff Training • Strategic Business Solutions • Force Development and Management • Organizational Assessments Design and Structuring • Democracy Transition Assistance Programs • New Equipment Integration and Training • Evaluations and Assessments • Logistics Planning, Management and Installation Operations • Doctrine Development • Peacekeeping and Humanitarian Aid • Anti-Terrorism/Force Protection • Law Enforcement Expertise • Investigations • Consequence Management

Non-statutory forces Rebels • Combat • Terrorism Warlords • Combat & terrorism • Marketing and outsourcing of violence Organized Crime • Criminal acts for economic gain

Mercenaries Type of activity: Infantry-type combat Legal status: Illegal, occasionally government-requested Main users: Besieged governments, rebel groups and insurgents, multinational corporations Main area of activity: War-torn societies, developing countries, ‘failed’ or ‘failing’ states

What has already been done? International Conventions 1977 OAU Convention for the Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa 1977 Protocol 1 Additional to the Geneva Conventions 1989 UN International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries The Establishment of the UN Rapporteur on Mercenarism The EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports The EU Commission has also adopted a Common Position on technical assistance that accompanies arms sales not dealt with under the EU Code National Regulations United States South Africa Europe The UK « Green Paper » National Laws against Mercenaries

International Conventions 1977 OAU Convention for the Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa • Does not cover activities of PMCs and PSCs • Does not include corporate criminal responsibility • Applicability limited to member states within the OAU • No real enforcement mechanism 1977 Protocol 1 Additional to the Geneva Conventions • Does not encompass the evolution of PMCs and PSCs • Definition is unworkable 1989 UN International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries • Does not impose total ban on mercenarism; only prohibits those activities aimed at overthrowing or undermining the constitutional order and territorial integrity of states • Repeats and reinforces deficiencies of the Additional Protocol • No monitoring or enforcement mechanism • Does not go far enough to curtail or regulate activities of PMCs and PSCs

The EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports Adopted in May 1998, only politically - not legally binding treaty Requires EU Member States to use one or more of 8 criteria to consider, on a case by case basis, requests for exports of military equipment, including small arms and light weapons, and dual use equipment 8 criteria: international commitments, human rights, internal conflict, regional peace and security, defense and national security, terrorism and international law, diversion, and sustainable development Most important developments: • Annual Consolidated EU Report on export licenses granted • Users Guide to the EU Code, clarifying responsibilities • Database of EU government license denials • Harmonizing end-use certification process • Common position on arms brokering • Agreement of an updated military list No legislation to control and monitor activities PMCs & PSCs

United States US Arms Export Control Act of 1968 Regulates both arms brokering and export of military services US companies offering military advice and services to foreign nationals in the US or overseas are required to register with, and obtain license from, the US State Department under the International Transfer of Arms Regulations (ITAR), implementing the Arms Export Control Act US administration must give Congress advance notice of sales valued at $50 million or more. PMCs & PSCs can also sell their services abroad through the US Department of Defense Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program, which does not require any licensing by the US State Department. Under FMS, the Pentagon pays the contractor for services offered to a foreign government, which in turn reimburses the Pentagon The US Federal Criminal Statute prohibits US citizens from enlisting or from recruiting others from within the US to serve a foreign government or party to a conflict with a foreign government with which the US is at peace

US domestic private security industry • No federal laws governing the domestic private security industry • State laws remain spotty • 16 States require no background checks • In 30 States no training is required, while in the others 1 to 48 hours are mandatory • In 22 States, PSCs do not have to be licensed

South Africa South African Regulation of Foreign Military Assistance Act (FMA) of 1998 No person within South Africa or elsewhere may recruit, use or train persons for, or finance or engage in mercenary activity Any PMC based in South Africa is compelled to seek government authorization for each contract it signs, whether the operation is local or extraterritorial Requests to supply assistance and all arms related materials are scrutinized by the National Conventional Arms Control Committee (NCACC), chaired by a minister having no direct links with the defense industry In most cases, the Act’s application depends upon the existence of armed conflict. The recipient must be party to the conflict. If the recipient was a private company in need of security services for legitimate concerns, the FMA would not apply

South Africa Security Industry Regulation Bill of 2001 Established Security Industry Regulatory Authority to: • receive, consider, grant or reject applications for registration and renewal from security providers • regulate the PSC industry • control security service providers • make quality assessments of training standards • prevent exploitation of PSC employees All companies and individuals engaged in any security service must register, or are liable for prosecution Equally, all domestic manufacturers, distributors, and importers of security equipment must register

European national legislation applicable to PMCs & PSCs • Varies throughout EU • No harmonized or overarching EU administrative framework or criteria • PMCs & PSCs have potential to carry out directly, or to facilitate, human rights abuses by non-state and state actors in the recipient country If this risk is to be minimized, it is vital that those companies operating within the rule of law are properly registered, and that international transfers of such services are subject to stringent export controls based upon international human rights and international humanitarian law

European Confederation of Security ServicesCoESS European regional organization of the Union Network International UNI-Europe CoESS set up in 1989, represents almost 10,000 PSCs in 14 European countries. The members are the national organizations of PSCs Objectives: • Defend interests of member organizations • Contribute to harmonization of national laws • Carry out economic, commercial, legal and social studies • Collect and disseminate information on the objectives fixed • Implement its European policy through frequent contacts with EU Commission • Hold social dialogue with UNI-Europe, its trade union counterpart

European Confederation of Security ServicesEuropean regional organization of the Union Network International - UNI-Europe In the European PSC sector, UNI-Europerepresents some 30 trade unions & 200,000 members Priorities of UNI-Europe in the PSC sector: • Development of the training of workers • Improvement of health and safety standards and career opportunities • Definition of decent social standards in all European countries • Development of negotiation at all levels on all questions related to the modernization of organization of work

What must be regulated? • Licensing system for PMCs & PSCs • Prohibition of certain activities • Definition of basic minimum requirements in terms of training, preparation, and behavior • Vetting and screening of personnel and firms • Monitoring of activities • Parliamentary oversight • Rules to make contracting competitive • Financing of regulation measures

Regulation If government proposes legislation to Parliament, it will wish to secure the following objectives: • Satisfy pressure for regulation of PMC & PSC activities • Ensure national and international legal compliance by the nation’s PMCs & PSCs • Increase government knowledge and understanding of the nation’s PMCs & PSCs • Enable the national PMCs & PSCs to bid more easily for outsourced government business

Regulation A wisely regulated environment for PMCs & PSCs is likely to have the following additional effects: • Assist in growing global perceptions of the legitimacy of national PMCs & PSCs • Attract new and diversifying PMCs & PSCs to operate from the state • Assist sector and PMC/PSC market share growth • Deter PMCs & PSCs from operating offshore

Licensing system for PMCs & PSCs 3-fold system of licensing: • Licensing the company: for a range of activities possible in a specified list of countries • Licensing the service capabilities: companies required to obtain license to undertake contracts for services abroad • Licensing or notification of individual contract: companies required to notify a federal agency of each contract prior to tendering/bidding

Prohibition of certain PMC activities Prohibition of activities involving: • Mercenary operations and operations by individuals • All combat services • All direct combat support services • ‘Core military’, ‘mission-critical’ or ‘emergency essential’ functions and services in zones of conflict • All arms brokering • All dual-use goods and NBC proliferation

PSCs and activities • PSCs should not be armed (except: transport of money & valuables, VIP protection) • Uniformly clad, but cloths must be clearly distinguishable from Police uniforms • No outsourcing of ‘monopoly of force’ and ‘core’ Police missions (no powers of arrest, no criminal investigation, etc) • Only ‘subsidiary’ engagements as legally ordered by state or communal authorities • Clear coordinated and defined cooperation in case of mass events, games, rally

State criteria by which PMC license applications will be assessed Criteria based on whether activities would inter alia: • Jeopardize public security and law & order • Undermine economic development • Enhance instability and human suffering • Augment threat perception in neighboring countries • Contribute or provoke internal intervention or external aggression • Violate international embargoes

More sensitive PMC activities requiring licensing • Strategic and military advice and training • Arms procurement • Intelligence collection & counterintelligence • Security and crime prevention services • Interrogation • Logistics support

Defining minimum requirements Fortransparency: • Ownership • Shareholding and financing arrangements • Declaration of Board Members and responsibilities • Identification of headquarters • Corporate or firm structure with divisional activities • Joint ventures and partners • Subsidiary & subcontractor ownership and interests • Contracts for outsourced services and clients

Defining minimum requirements Foraccountability: • Qualification of Board of Directors, corporate or firm leadership and duties of public disclosure • Capacities and means for recruitment of personnel, preparation of operations and provision of adequate training • Enforceable performance standards • Code of Conduct

Defining minimum requirements For employment–recruitment, qualification, preparation, training and conduct of personnel: • No criminal record • No human rights violations • No violation of International Humanitarian Law • No dishonorable discharge from the Armed Forces, etc Personnel must be acquainted with human rights law, International Humanitarian Law, and gender issues, etc

Screening & vetting of firms and personnel • Government should either provide screening and vetting for PMC/PSC owners, CEOs and leadership, staff and employees, or establish rules for the outsourcing of such processes to independent private organizations • Centralized database should be established, and cooperative declarations signed by all parties involved • Companies are required to keep register of staff that can be reviewed periodically by government inspectors

Monitoring • Monitoring of activities of PMCs & PSCs must be established • PMC & PSC activities should also be monitored in ways comparable to application of arms exports, non-proliferation, dual-use goods and general export controls • This helps to provide transparency and international standards of conduct for PMCs & PSCs

Parliamentary oversight • Parliamentary oversight over outsourcing of PMC & PSC services delivered abroad and contracted by the own or by foreign governments or multinational corporations • Oversight must be subject to same reporting requirements as is the case for arms export licenses, non-proliferation, and dual-use goods export controls • Parliament should be given powers to scrutinize more sensitive contracts before authorization is granted

Rules to make contracting process competitive and monitored • No ‘sole-source’ contracting • No ‘no-bid’ contracting • No ‘cost-plus’ contracting • ‘Indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity’ contracting questionable • Excluding ‘revolving door’ practices = prohibit government employees from regulating or contracting private sector firms that formerly employed them

Securing the financing of regulation measures Private military and security industry should participate in the financing by: • Fee for registration • Fee for contract licensing & renewal • Fee for each inspection • Payment of annual or monthly fees per company and per registered employee

Longer-term efforts to set basis for international regulation • Update and amend existing international conventions to include PMC & PSC activities, issues of transparency, accountability of firms and accountability of employees • New and expanded role for UN Rapporteur for Mercenaries that could improve monitoring of PMC & PSC activities

Database of vetted firms UN should set up database of vetted firms available for hire. The model is the UN Register of Conventional Arms, which compiles declarations by both importers and exporters of conventional arms Register should contain declarations by the importers, the states or groups employing PMCs & PSCs, and the exporters – the firms themselves

21st Century: “War is far too important to be left to CEOs of an unregulated private military and security industry”