Social Constructivism vs. Positivism

380 likes | 1.61k Vues

Social Constructivism vs. Positivism. The most recent debate in IR theory. Introduction. Realism, Liberalism, and Marxism together comprised the inter-paradigm debate of the 1980s, with realism dominant amongst the three grand theories.

Social Constructivism vs. Positivism

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Social Constructivism vs.Positivism The most recent debate in IR theory

Introduction • Realism, Liberalism, and Marxism together comprised the inter-paradigm debate of the 1980s, with realism dominant amongst the three grand theories. • Despite promising intellectual openness at the beginning, however, the inter-paradigm debate ended by shoring up the dominance of realism; that there was real contestation of paradigms is open to question.

Introduction • In recent years, the dominance of realism has been undermined by three developments: • first, neo-liberal institutionalism has become increasingly important; • second, globalization has brought a host of other, non-theoretical features of world politics to centre-stage; • third, positivism, the underlying methodo-logical assumption of realism, has been significantly undermined by developments in the social sciences and in philosophy.

Introduction While neorealists – and also neoliberals – hold a materialist view of international politics, other theorists develop an ideational perspective: At bottom, the difference is between the assumption • that I.P. are driven by power and national interest, with power in the end defined as military capabilities supported by economic and other resources, and national interest defined as a state‘s desire for power, security, and wealth, • that the material world is indeterminate & has to be interpreted within a larger context of meaning defined by ideas and expressed by (different) language(s)

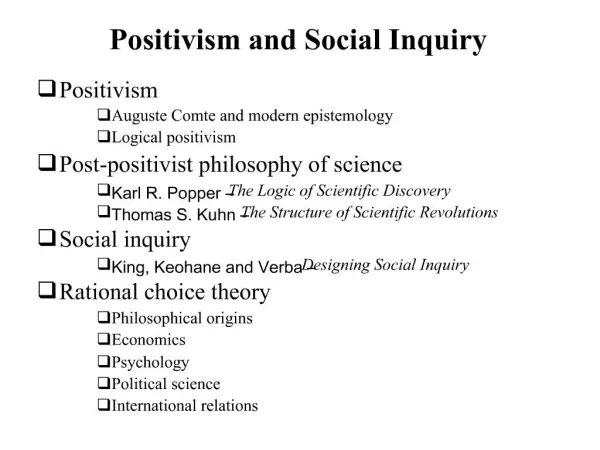

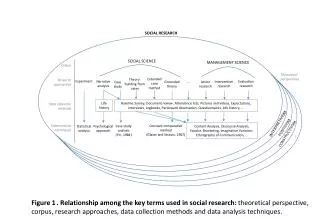

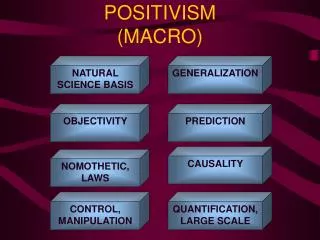

Theoretical developments I • The main non-marxist theories comprising the inter-paradigm debate were based on a set of positivist assumptions, namely the idea that social science theories can use the same methodologies as theories of the natural sciences, that facts and values can be distinguished, that neutral facts can act as arbiters between rival truth claims, and that the social world has regularities which theories can ‘discover’.

Positivism I • Axioms: correspondence theory of truth, methodological unity of science, value-free scientific knowledge • Premisses: Division of Subject and Object, Naturalism – deduction of all phenomena from natural facts, Division of statements of facts and statements of values

Positivism II • Consequences: • Postulated existence of a „real“ world (Object) independent from the theory-loaded grasp of the scientist (Subject); • identification of facts in an intersubjectively valid observation language independent from theories; • methodological exclusion of idiosyncratic characteristics and/or individual (subject) identities assures objective knowledge of an intersubjectively transferable character • Postulate of like regularities in the natural as well as the social world, independent of time, place, and observer, enables the transfer of analytic approaches and deductive-nomological processes of theory formulation from the field of the natural to the field of the social sciences & to the analysis of social/societal problems • Knowledge generated on the basis of positivist research approaches and methodologies is limited to the objective (i.e. empirical) world. Statements and decisions on values are outside the sphere of competence of science.

Positivism III • Further Consequences: • Concept of Reason predicated on thepurposeful rationality/rationality of purpose of instrumental action aiding the actor to technically master her/his environment • Rationalisation of societal (inter-)action by its predication on planned/ plannable means-end-relationships, technical (or engineering) knowledge, depersonalisation of relationships of power and dominance, and extension of control over natural and social objects (“rationalisation of the world we live in”) • Theory regards itself as problem-solving theory, which accepts the institutions and power/dominance relationships of a pre-given reality as analytical and reference frameworks, and strives for the explanation of causal relationships between societal phenomena; its aim is the elimination of disturbances and/or their sources in order to insure friction-less action/functioning of social actors • International politics is regarded as the interaction of exogeneously constituted actors under anarchy, the behaviour of which is as a rule explained by recourse to the characteristics or parameters of the international system (top-down explanation)

Theoretical Developments II • Since the late 1980s there has been a rejectionof positivism,mainly due to the insight that its stringent methodological criteria do not fit the Social Sciences • The current theoretical situation is one in which there are three main positions: • first, rationalist theories that are essentially the latest versions of the realist and liberal theories; second, alternative theories that are post-positivist; • and thirdly social constructivist theories that try to bridge the gap.

Theoretical Developments III • Alternative approaches at once differ considerably from one another, and at the same time overlap in some important ways. One thing that they do share is a rejection of the core assumptions of rationalist theories: • that there is indeed an outside world which can be experienced and analyzed like natural phenomena, • and that this world is materialist, that I.R. focuses on how the distribution of material power, e.g. military forces & economic capabilities, defines balances of power between states & explains their behaviour

Theoretical Developments IV „Constructivists, as a rule, cannot subscribe to mechanical positivist conceptions of causality. That is because the positivist do not probe the intersubjective content of events and episodes. For example, the well-known billiard ball image of international relations is rejected by construc-tivists because it fails to reveal the thoughts, ideas, beliefs and so on of the actors involved in international conflicts. Constructivists want to probe the inside of the billiard balls to arrive at a deeper understanding of such conflicts.“ Jackson/Sorensen, Introduction to I.R. Theories and Approaches, 3e., p.166 (my emphasis)

Historical sociology • Historical sociology has a long history, having been a subject of study for several centuries. Its central focus is on how societies develop the forms that they do. • Contemporary historical sociology is concerned above all with how the state has developed since the Middle Ages. It is basically a study of the interactions between states, classes, capitalism, and war.

Historical sociology • Like realism, historical sociology is interested in war. But it questions neo-realism because it shows that the state from a functional point of view is not all the same or similar organization, but instead has changed over time. • Raymond Aron: Paix et guerre entre les nations (1962)

Normative theory • Normative theory was out of fashion for decades because of the dominance of positivism, which portrayed it as ‘value-laden’ and ‘unscientific’. • In the last twenty years or so there has been a resurgence of interest in normative theory. It is now more widely accepted that all theories have normative assumptions either explicitly or implicitly.

Normative theory • The key distinction in normative theory is between cosmopolitanism and communitarianism. The former sees the bearers of rights and obligations as individuals; the latter sees them as being the community (usually the state). • Main areas of debate in contemporary normative theory include the autonomy of the state, the ethics of the use of force, and international justice.

Normative theory • In the last two decades, normative issues have become more relevant to debates about foreign policy, for example in discussions of how to respond to calls for humanitarian intervention and whether war should be interpreted in terms of a battle between good and evil. • F.H.Hinsley: Power and the Pursuit of Peace. Theory and Practice in the History of Relations between States (1967) • Geoffrey Best: Humanity on Warfare. The Modern History of the International Law of Armed Conflict (1980)

Post- modernism I • Lyotard defines post-modernism as incredulity towards metanarratives, meaning that it denies the possibility of foundations for establishing the truth of statements existing outside of discourse. • Foucault focuses on the power-knowledge relationship and sees the two as mutually constituted. It implies that there can be no truth outside of regimes of truth. How can history have a truth if truth has a history?

Post- modernism II • Foucault proposes a genealogical approach to look at history, and this approach uncovers how certain regimes of truth have dominated others. • Derrida argues that the world is like a text in that it cannot simply be grasped, but has to be interpreted. He looks at how texts are constructed, and proposes two main tools to enable us to see how arbitrary are the seemingly ‘natural’ oppositions of language. These are deconstruction and double reading.

Post- modernism III • Post-modern approaches have been accused of being ‘too theoretical’ and not concerned with the ‘real world’. They reply, however, that in the social world there is no such thing as the ‘real’ world in the sense of a reality that is not interpreted by us. Despite their methodological preoccupation, they have done a great deal of work on important empirical questions, e.g. the explanation of the reasons for war. • Cynthia Weber: International Relations Theory. A critical introduction (2001) • Jim George: Discourses of Global Politics: A Critical (Re)Introduction to International Relations (1994)

More Literature • Iver B. Neumann/Ole Waever (eds.): The Future of International Relations. Masters in the Making (1997) • Gert Krell: Weltbilder und Weltordnung: Einführung in die Theorie der Internationalen Beziehungen (4th ed. 2009) • Siegfried Schieder/Manuela Spindler (eds.): Theorien der Internationalen Beziehungen (2003), 2nd ed.2006

The Rise of Constructivism I • The end of the Cold War meant that there was a new intellectual space for scholars to challenge existing theories of international politics. • The end of the Cold War also implied that the prognostic value of neorealist theory was more than questionable. • Constructivists draw on established sociological theory in order to demonstrate how social science could help I.R. scholars understand the role of ideas, and the importance of social interaction between states as well as of definitions of identity and norms in world politics.

The Rise of Constructivism II • Constructivists demonstrated how attention to norms and states’ identities could help uncover important issues neglected by Neorealism and Neoliberalism – i.e. • the social construction of reality • the relationship between actors and structures • the content and importance of intersubjective ideas and shared beliefs that define international relations • Yosef Lapid/Friedrich Kratochwil (eds.): The Return of Culture and Identity in IR Theory (1996)

Precursors Harold & Margaret Sprout: The Ecological Perspective on Human Affairs. With Special Reference to International Politics. Princeton, Princeton UP 1965 „…environmental factors (both nonhuman and social) can affect human activities in only two ways. Such factors can be perceived, reacted to, and taken into account by the human individual…under conside-ration. In this way, and in this way only, environ-mental factors can be said to „influence“, or to „condition“, or otherwise to „affect“ human values and preferences, moods and attitudes, choices and decisions.“ 2nd option: environmental factors operate as a sort of matrix which limit the execution of decisions or undertakings

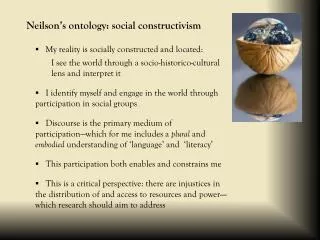

Constructivism I • Constructivists • are concerned with human consciousness, • treat ideas as structural factors, • consider the dynamic relationship between ideas and material forces as a consequence of actors’ interpretation of their material reality, • and are interested in how agents produce structures and how structures produce agents. • Knowledge shapes how actors interpret and construct their social reality.

Constructivism II • Normative structures shape the identity and interests of actors such as states. • Social facts such as sovereignty and human rights exist because of human agreement while brute facts such as mountains are independent of such agreements. • Social rules are regulative, regulating already existing activities, and constitutive, making possible and defining those very activities.

Constructivism III • Social construction questions what is taken for granted, asks questions about the origins of what is now accepted as a fact of life and considers the alternative pathways that might have produced and can produce alternative worlds. • Power can be understood not only as the ability of one actor to get another actor to do what she/he would not do otherwise but also as the production of identities and interests that limit the ability to control their fate.

Constructivism IV • Although the meanings that actors bring to their activities are shaped by the underlying culture, meanings are not always fixed but are a central feature of politics. • Maja Zehfuss: Constructivism in International Relations. The Politics of Reality (2002) • Cornelia Ulbert/Christoph Weller (eds.): Konstruktivistische Analysen der internationalen Politik (2005)

Constructivism and Global Change I • The recognition that the world is socially constructed means that constructivists can investigate global change and transformation. • A key issue in any study of global change is diffusion, captured by the concern with institutional isomorphism and the life cycle of norms.

Constructivism and Global Change II • Institutional isomorphism and the internationalization of norms raise issues of growing homogeneity in world politics, assuming a deepening international community, and intensifying international socialization processes. • Vendulka Kubalkova/Nicholas Onuf/Paul Kowert (eds.): International Relations in a Constructed World (1998)

Epistemological Background: Constructivism - ResuméI • Epistemological Premiss: • Knowledge/Cognition is the result of a circular gestalt formation process, which produces „reality“ in perception and thinking • „Die Umwelt, die wir wahrnehmen, ist unsere Erfindung.“ [H.v.Foerster: Wissen u. Gewissen, 1993] • Ontological Consequences: • Social Phenomena or „facts“ are not simply given, but they are generated or produced by human beings, which hand them on over time, explain them, justify them.

Epistemological Background: Constructivism - ResuméII Constructivists do not agree on the extent to which it is possible to follow the explanatory model of the natural sciences and produce scientific ex-planations based on hypotheses, data collection, and generalizations. On the one hand, they reject the notion of objective truth: social scientists cannot discover a final truth about the world which is true across time and place. On the other hand, constructivists too make truth claims about the subjects they have investigated; yet they admit that their claims are always contingent and partial interpretations of a complex world.

Constructivism Resumé III • Processes & structures of IR are socially constructed, i.e. rather social & intellectual than material phenomena. Structural conditions of the international system are no given phenomena external to the actors (as e.g. in Neorealism), but social constructs intuitively understood by the actors and (re-)produced by their interactions [A.Wendt: „Anarchy is what states make of it: theSocial Construction of Power Politics“, IO 46(2)], • The behaviour of actors is not exclusively dominated by the system [as in Neorealism], but it creates and changes the system structure. Structure is (repeated) behaviour solidified over time: • „...the structures of international politics are outcomes of social interactions, ...states are not static subjects, but dynamic agents, ...state identities are not given, but (re)constituted through complex, historical overlapping (often contradictory) practices – and therefore variable, unstable, constantly changing; ...the distinctions between domestic politics and international relations are tenuous...“ [Knutsen 1997, 281ff] • T.I. Knutsen: A History of International Relations Theory. Manchester: Manchester UP 1997

Constructivism – Resumé IV • New perspective on the agency – structure – problem: • Neither structural determinism nor individual intentionalism are acceptable starting points for theory formulation. [ Duality or even Dialectics of agency and structure, Giddens 1984 ] Actors act inside a framework of structures (and to that extent their actions are influenced by structures), but actors can change structures by their own actions. I.e. – actors and structures constitute each other. • „...points of departure are the rules, norms and patterns of behaviour that govern social interaction. These are structures, which are on the one hand, subject to change if and when the practice of actors changes, but on the other hand structure political life as actors re-produce them in their every day actions...“ [Christiansen/Jorgensen 1999]. • Anthony Giddens: The Constitution of Society. Berkeley 1984 • Thomas Christiansen and Knud Erik Jørgensen: The Amsterdam Process: A Structurationist Perspective on EU Treaty Reform, in: http://www.eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/1999-001a.htm