Functional Behavioral Assessment for Students with Autism

540 likes | 687 Vues

Functional Behavioral Assessment for Students with Autism. Mediasite Presentation September 19, 2008 Marge Resan, Education Consultant Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. Autism in Wisconsin Schools.

Functional Behavioral Assessment for Students with Autism

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Functional Behavioral Assessment for Students with Autism Mediasite Presentation September 19, 2008 Marge Resan, Education Consultant Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

Autism in Wisconsin Schools • The numbers of children with autism receiving special education services in Wisconsin based on December 1 child count: • 1992-93: 203 • 2002-03: 3,079 • 2003-04: 3,669 • 2005-06: 5085 • 2006-07: 5635 • 2007-08: 6217 • Since 2002 – more than doubled.

Autism in Wisconsin Schools What are the reasons for this increase? • Better medical identification? • Better educational identification? • Corresponding decline in other disability areas? • A true increase in incidence?

Autism in Wisconsin Schools • We don’t know… • 2008 - California Department of Public Health study – seems to point to a true increase in incidence. • Numbers increased January 1995-March 2007. • Increases continued after mercury removed from vaccines in 1999.

Autism in Wisconsin Schools • Autism spectrum disorders are: • Developmental disabilities. • Usually evident before age three. • Neurological disorders.

Autism in Wisconsin Schools • Autism is considered a spectrum disorder, meaning physical differences in the brains of individuals with autism create • Vastly differing neurological experiences; • A wide continuum of symptoms; • A range in severity; • Wide variability among students.

Autism in Wisconsin Schools • Autism spectrum disorders occur across all socioeconomic, ethnic, cultural and geographic groups. • The incidence of autism spectrum disorders is higher among males than females.

Autism in Wisconsin Schools • When students with autism present behavior challenges, • Schools are at often a loss as to how to manage those behaviors. • Each student has a different sensory, communication and learning profile. • Behaviors can be very different and difficult to understand. • All behavior is communication!

Why do behavior challenges occur so commonly among individuals with autism spectrum disorders? Difficulties with Communication Skills From Wisconsin Administrative Code, PI 11 • “The child displays problems which extend beyond speech and language to other aspects of social communication, both receptively and expressively.” • Understanding meaning of other’s language is difficult. Sharing thoughts and feelings, making requests or making needs known is difficult. • Not that the child does not want to communicate…

Why do behavior challenges occur so commonly among individuals with autism spectrum disorders? Difficulties with Social Skills • “The child displays difficulties or differences or both in interacting with people and events. The child may be unable to establish and maintain reciprocal relationships with people.” • Understanding and relating to others, including peers, is difficult. • Not that the child does not want to establish and maintain social relationships…

Why do behavior challenges occur so commonly among individuals with autism spectrum disorders? Restricted Interests / Movement Differences • “The child displays marked distress over changes, insistence on following routines, and a persistent preoccupation with or attachment to objects.” • “Perseverant thinking and impaired ability to process symbolic information may be present.” • Familiar areas of special interest or expertise become focus. • Sometimes child become “stuck”. • Not that the child wants to be stubborn or inflexible…

Why do behavior challenges occur so commonly among individuals with autism spectrum disorders? Sensory Processing Differences • “The child exhibits unusual, inconsistent, repetitive or unconventional responses to sounds, sights, smells, tastes, touch or movement.” • Child’s neurology makes sensory system hypo or hyper sensitive. • Not that the child chooses to react negatively or to be compelled to seek out certain sensory experiences…

Neurology of Autism • We know that autism is a neurological issue. Its basis is within the brain. Individuals with autism have a different sort of neurology that creates a very different experience. • Different as compared to individuals with more typical neurology… • And different as compared to other individuals with autism.

Neurology of Autism • “Like being a Mac in a PC World…” (Notbohm) • Important to keep in mind: This differently structured neurology is not indicative of the student’s ability.

Neurology of Autism • Multiple studies have found children with autism have increased white matter in their brains. (Dr. Martha Herbert, Harvard Medical School, Dr. Eric Courchesne University of California-San Diego) • Studies have used Magnetic Resonance Imagery (MRI) to study brains of children with autism. • White matter is the part of the brain that carries information from one section of the brain to another.

Neurology of Autism • This increase is located in areas of the brain that are close to each other and on the same side of the brain. • Since there is an increase in connections running within each brain half as compared to between brain halves, it may be harder for information on one side of the brain to be shared with the other.

Neurology of Autism • Brain areas are often bigger on the side to which they are lateralized (perhaps to handle their increased work load). • For example, language function is lateralized to the left brain, and the areas of the brain which handle language processing are correspondingly bigger on the left than the right side. • Studies have shown that children with autism have a reversal of the brain asymmetry - there are more areas that are bigger on the right than the left side of the brain, making the brain size biased overall to the right half.

Neurology of Autism • This is opposite of what is found in the brains of typically developing children. • Very similar changes are seen in the brains of children with language impairment disorders. • The similarity between the disorders highlights the fact that the anatomical problems may underlie the inability to process complex information such as language.

Neurology of Autism Another set of findings: • Dr. Margaret Bauman, a pediatric neurologist at Harvard Medical School, has examined postmortem tissue from the brains of nearly 30 autistic individuals who died between the ages of 5 and 74. • Found striking abnormalities in the limbic system, an area that includes the amygdala (the brain's primitive emotional center) and the hippocampus (a seahorse-shaped structure critical to memory).

Neurology of Autism • Bauman’s work shows the cells in the limbic system of individuals with autism are atypically small and tightly packed together, compared with the cells in the limbic system of their more neurologically typical counterparts. • University of Chicago psychiatrist Dr. Edwin Hook comments that these cells look unusually immature "as if waiting for a signal to grow up."

So what does this mean to our work as educators? • We know that there are physical, neurological bases for the differences in children with ASD’s. • If this is a physical, neurological difference, then it is reasonable to believe that behaviors are usually not indicative of the child’s intent to misbehave. • The child is unable to process the relevant information in the expected manner – this is why we see behaviors. • The child’s neurology does not support the expectations.

So what does this mean to our work as educators? • Is this to say children with autism never have behaviors “on purpose”? • No – but it is far less damaging to educator/child relationship to presume that behavior is related to neurology and not intentional.

Looking at Functional Behavioral Assessment through the Autism Lens • DPI Information Update Bulletin No. 07.01 – Addressing the Behavioral Needs of Students with Disabilities • Available at http://dpi.wi.gov/sped/bul07-01.html

What does the law require when a child’s behavior “impedes his or her learning or that of others?” • Individualized Education Program (IEP) team is to “consider the use of positive behavioral interventions and supports and other strategies to address that behavior.” • IEP team must think about supports and interventions that will facilitate appropriate behavior. • IEP team must include a plan to teach the child strategies to manage his or her behavior positively.

What is functional behavioral assessment? • A continuous, systematic process for identifying: • The purpose or function of the behavior, and • The variables that influence the behavior. • Leads to components of an effective behavioral intervention plan. • Based on paradigm of Antecedent > Behavior > Response or Consequence

Paradigm of Antecedent > Behavior > Response or Consequence Antecedent – that which precedes behavior of concern. • External factors such as settings, tasks, people, activities, and events. • “In regular education history class on days with are cooperative group activities”. • “During journal time when paraeducator is prompting student to free write”. • “On rainy days in the lunch room when the noise level is high”.

Paradigm of Antecedent > Behavior > Response or Consequence • Antecedents may also include internal factors such as the child’s neurology, mood, medical condition. • Don’t overlook possible medical conditions!

Paradigm of Antecedent > Behavior > Response or Consequence Behavior • Important to define the behavior in OBSERVABLE, FACTUAL terms. • Everyone supporting the student must understand the definition of the behavior.

Paradigm of Antecedent > Behavior > Response or Consequence • Compare terms: • “Disruptive classroom behavior” to “rises from seat and paces quickly around perimeter of room”. • “Verbal outburst” to “to “face reddens, hands begin to shake, student shouts phrases such as ‘I’m going to throw this chair’”. • “Self-injury” to “Repeatedly strikes forehead with ball of right hand with enough force to leave red marks”.

Paradigm of Antecedent > Behavior > Response or Consequence Response or Consequence– that which follows the behavior of concern • What does the student do? What do others do? What else happens? • “Other students in cooperative group move away from and ignore student.” • “Para removes student from room and activity” ends.” • “Student appears sleepy (eyes close, slumps in chair) and begins to cry.”

What are some of the common functions of behavior? • We must keep in mind the unique characteristics of students with autism when we consider functions of behavior. • Refocus your camera: • Crucial to address this question by viewing behavior through our lens of autism.

What are some of the common functions of behavior? • Some common functions of behavior: • Seeking attention: common, but often inaccurate if it’s the only function considered. • Escape or avoidance: avoiding a particular activity, person, group, unpleasant situation, uncomfortable, overwhelming or painful sensory stimuli, etc.

What are some of the common functions of behavior? • Common functions of behavior (cont.) • Justice or revenge: Not common among students with autism! • Acceptance and affiliation: belonging or gaining acceptance to a group, desire to belong when rules of “hidden curriculum” are not understood.

What are some of the common functions of behavior? • Common functions of behavior (cont.) • Power or control: Control environments, control overwhelming sensory situations, gain control over highly stressful situations. • Expression of self: seeking to announce independence and/or individuality, attempt to communicate.

What are some of the common functions of behavior? Common functions of behavior (cont.) • Access to tangible rewards or personal gratification: Tangible reinforcement (food, money, etc.), sensory input, approval from peers, etc. • Others – we need to be observant, thorough and open-minded. • Remember that behavior is communication! • Behaviors often serve more multiple functions.

When must schools conduct FBA’s? • Per IDEA: • Legally required when a disciplinary change of placement occurs and the behavior is determined to be a manifestation of the disability. • If there is a change of placement and the behavior is not a manifestation of the disability, an FBA should be conducted “as appropriate.”

When must schools conduct FBA’s? • Per DPI Directives: • As part of an Individualized Education Program (IEP) team meeting required after the first unanticipated instance of the use of physical restraint or seclusion/time out. • WDPI Directives for the Appropriate Use of Seclusion and Physical Restraint in Special Education Programs available at: http://dpi.wi.gov/sped/doc/secrestrgd.doc

When must schools conduct FBA’s? • It is good practice to conduct FBA: • Whenever behaviors are a concern. • When current programming is not effective. • When student or others are at risk of harm or exclusion. • When a more restrictive placement or a more intrusive intervention is contemplated. • Whenever there are repeated and serious behavior problems. • Can and should be used any time we seek to better understand what a child is doing!

Is the FBA process the same in every situation? • Short answer – No! • No specific format is required. • You will choose the format on a case-by-case basis. • Tools available to help you get started available at: http://dpi.wi.gov/sped/sbfba.html

How do we begin to collect data about the behavior? • Use both direct and indirect methods of data collection. • Indirect methods: Talking to the individuals who know the student best. Understand that this information is filtered through the interviewees (their experience, emotion, relationship to the student). • Also includes review of records and work samples.

Data Collection: • Direct methods: Observe the student in typical activities and routines. Know that these are only snapshots and might not be authentic. • Both types of data are necessary to verify each other! No one source of information can stand alone.

Some tips for Observations: • Observe student across settings and at a variety of different times. • Keep the recording system as simple as possible. • Accurately define behavior – you must know what you are looking for! • Get appropriate background info.

Skill Deficits v. Performance Deficits Is the behavior a skill deficit or a performance deficit? • Skill deficit: Student cannot do this. Lacks necessary information or component skill. • Performance deficit: Motivation, might perform skill on one setting but has not generalized to another, etc. • Caution – You often cannot tell! Which assumption provides the least potential damage to the relationship?

What are the crucial dimensions of behavior? • Frequency – how often the behavior occurs; • Topography – the description of the behavior; what it looks like (in seat, on task); • Duration – how long the behavior lasts; • Latency – the amount of time that elapses between “A” and “B”; for example, the amount of time between a teacher giving a direction and the student complying with that direction;

What are the crucial dimensions of behavior? • Magnitude – force or power of the behavior (5 minute tantrum vs. a 30 minute tantrum; mumbling vs. talking loudly); • Locus – where the behavior occurs (gym class vs. English class; structured time vs. unstructured time).

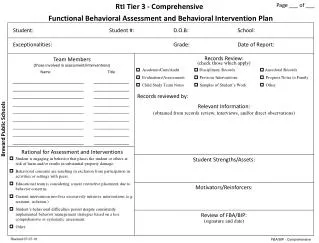

How do we incorporate FBA results into the IEP? • Per IDEA, if the student’s behavior is interfering with his/her learning or that of others, the IEP must address the behavior. • FBA provides baseline data for appropriately addressing the student’s behavioral needs.

How do we incorporate FBA results into the IEP? • Can include FBA results in Present Level of Performance • FBA results can provide basis for annual goals • Be mindful of IDEA’s emphasis on positive interventions, strategies and supports.

What are positive behavioral interventions and supports? • IEP team cannot develop appropriate strategies, supports and interventions unless the meaning behind the behavior is understood. • Strategies and supports based on functional behavioral assessment. • Attempt to understand the purpose of a problem behavior so it can be replaced with new appropriate behaviors.

What are positive behavioral interventions and supports? • Developmentally, chronologically, cognitively and functionally appropriate for the student. • Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports focus on : • Modifying environmental factors to try to prevent challenging behaviors • Addressing behavior programmatically by teaching replacement behaviors and skills. • Promote long-term, lasting behavior change.

What are positive behavioral interventions and supports? • Not about “fixing the student”. It’s fixing student skill deficiencies, classroom settings, instructional delivery and/or curricular adaptations to support the student’s success. • Not crisis management!