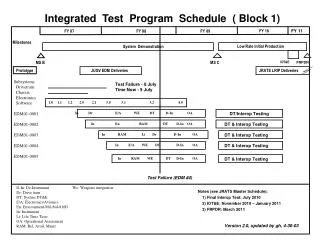

Maximizing Instruction with a Block Schedule

140 likes | 385 Vues

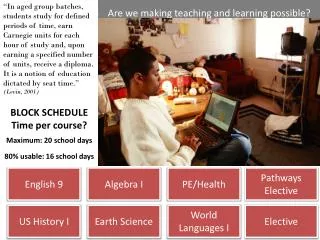

Maximizing Instruction with a Block Schedule. Problem. Student Teaching Experience vs. New Job Teaching Freshman for 90 minutes Glencoe’s Schedule Typical Lesson Set Up In-class reading- 15 minutes Lecture- 20 minutes

Maximizing Instruction with a Block Schedule

E N D

Presentation Transcript

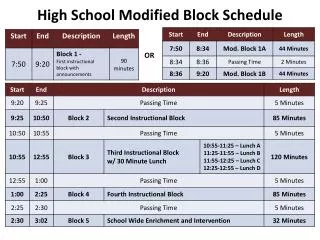

Problem • Student Teaching Experience vs. New Job • Teaching Freshman for 90 minutes • Glencoe’s Schedule • Typical Lesson Set Up • In-class reading- 15 minutes • Lecture- 20 minutes • In-class assignment (ex. Timelines, maps, news articles and questions, movies, t-charts, study guides, review games, worksheets)

In-Class Discussion with Students produced the following comments: “It seems like a lot of teachers don’t teach much. They just give us an assignment and have us work on it.” “Most of my teachers just lecture us. It works a lot better when we do interesting things.” “90 minutes is really long, especially when we don’t do much in class.” “I like honors biology because we get do hands-on stuff and experiments that are cool.” “It seems like our teachers don’t know what to do with us sometimes, but then when we have short classes on Mondays, we don’t even do anything.” “I don’t mind taking notes sometimes, but if we have to take them for a long time I stop learning.” “We hardly ever get homework. Most of the time we can get it done in class. I like that part.” Evidence- Student Perceptions

Evidence- Teacher Reflection • “For my first year of teaching, I feel like the quote “sink or swim” fits the way I feel most of the time. Having 4 preps and being a varsity coach is a little overwhelming, but I know I just need to get through the first year.” • “I am scared to death of having to teach for 90 minutes. It was hard enough student teaching for 50 minutes. Oh well, at least I have a job. I am sure I will figure things out.” • “I feel like I am doing the best I can, but I know I can be a more effective teacher. Unfortunately, lack of time makes it very difficult to be as good as I would like to be. I can see how teachers can get stuck in what is easy, but I do want to learn more strategies so that I can become a better teacher.”

Research/Support • Planning: “Research and practice suggest that one major way to influence the prospects and probability for success is through careful planning, preparation, monitoring implementation efforts, and feedback.” (Robbins, Gregory, & Herndon, 2000, p. 187) • Variety in Instruction: “Teachers gain additional time increasing the potential to implement creative and diverse student-centered instructional practices or pedagogical techniques and flexible assessment/evaluative strategies that could not otherwise be utilized under traditional schedules.” (McCreary & Hausman, 2001, p. 5) • Hands-On Learning: “Likewise, Fogarty (1996), O’Neil (1995), Queen, Algozzine, and Eaffy (1998), and Reither (1999) suggest that longer instructional periods may increase in-depth learning through learning-centered approaches, like cooperative learning, student-directed projects, and group work.” (McCreary & Hausman, 2001, p. 6)

Research/Support • Lecture-Based Instruction: “Canady and Rettig (1993) argue that the simple intervention of increasing the amount of time a teacher is exposed to students in the classroom can lead to experimentation with learning activities that increase student engagement and satisfaction. They state that teachers should be encouraged to break away from over-reliance on lecture/discussion as the primary (often only) model of teaching.” (Staunton, 1997, p. 74) • Professional Development: “When block scheduling fails, it is often for four reasons: (1) schools jump into it too hastily; (2) administrators impose it from the top, unsympathetic to the teachers', students', or community's feelings;(3) teachers aren't given training in instructional strategies for the new delivery system; and (4) it is implemented without sufficient examination of other school policies.” (Freeman & Scheidecker, 1996)

Final Solution Final Solution: I will create a 5-week geography unit utilizing strategies that have been recommended by the research I have conducted. My new unit has 5 different focus points which are listed below: • 1. A unit plan will be created for the geography unit that includes goals, objectives, activities and assessments. • 2. Each lesson will include at minimum 3 different activities. • 3. At least one “hands-on” activity will be included in each class period. • 4. In-class lectures will take place 1-2 times per week for no longer than 15-20 minutes each class period. • 5. I will seek out at least one professional development opportunity to help me continue to learn effective teaching strategies that can be utilized during block periods.

Strengths and Weaknesses • Planning for 90-Minute Classes • Quality vs. Time and Effort • Variety in Instruction • Learning Styles, Active Instruction vs. Time and Effort • Hands-On Learning • Student-Centered vs. Time and Effort, Training, Comfort Zone • Lecture-Based Instruction • Communicating Information vs. Learning Styles, Difficulty Focusing • Professional Development • Focus on Improvement, New Strategies vs. Time and Effort

Research Plan • Research Questions • How effective is my new geography unit in comparison to my old geography unit? • Does my new geography unit increase the learning rate of those students exposed to it in comparison to my old geography unit? • Research Plan • Non-Equivalent Control Group Design • Pretest/Posttest • Results: Graph Learning Rate, Class Averages • Qualitative: Open-Ended Survey

Threats to Validity • Information communicated to each class • Variance in my treatment group and control group • First time teaching new unit, experience teaching old unit

How to Surpass Threats to Validity • Observations and Reflection • Learning Rate, not Class Averages • Repeating the Study

Follow Up & Conclusion • Open-ended survey regarding instructional methods • Informal group discussion " Every successful learning initiative requires key people to allocate hours to new types of activities: reflection, planning, collaborative work, and training." Peter Senge, The Dance of Change

References • Adams, D., Salvaterra, M. (1997). Structural and Teacher Changes: Necessities for Successful Block Scheduling. High School Journal, 81, 98-107. Retrieved July 10, 2006, from Ebsco Academic Search Elite Database. • Freeman, W., Scheidecker, D. (1996). Planning for Block Scheduling. Clearing House, 70, 60-62. Retrieved July 10, 2006, from Ebsco Academic Search Elite Database. • Hayley, M. (1997). Surviving Block Scheduling. Nashville, TN: Annual Meeting of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 427529). • Marshak, D. (1998). Key Elements of Effective Teaching in Block Periods. Clearing House, 72, 55-57. Retrieved July 2, 2006 from Ebsco Academic Search Elite Database. • Marshak, D. (2001). Improving Teaching in the High School Block Period. Maryland: Scarecrow Press. • McCreary, J., Hausman, C. (2001). Differences in Student Outcomes between Block, Semester, and Trimester Schedules. Salt Lake City, Utah. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 457590). • Porter, C. (2002). What do I teach for 90 minutes? Creating a Successful Block Scheduled English Classroom. Illinois: National Council of Teachers of English. • Queen, J. (2000). Block Scheduling Revisited. Phi Delta Kappa International. Retrieved July 3, 2006 from http://www.pdkintl.org/kappan/kque0011.htm. • Queen, J. (2003). The Block Scheduling Handbook. California: Corwin Press. • Robbins, P. Gregory, G. Herndon, L. (2000). Thinking Inside the Block Schedule. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. • Staunton, J. (1997). A Study of Teacher Beliefs on the Efficacy of Block Scheduling. NASSP Bulletin, 81 (593), 73-80. • Veal, W., Flinders, D. (2001). How Block Scheduling Reform Effects Classroom Practice. High School Journal, 84, 21-32. Retrieved July 10, 2006, from Ebsco Academic Search Elite Database. • Wyatt, L. (1996). More Time, More Training. What Staff Development Do Teachers Need for Effective Instruction in Block Scheduling? In D. Flinders (Ed.), Block Scheduling: Restructuring the School Day (pp. 267-269). Indiana: Phi Delta Kappa.