Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion

390 likes | 590 Vues

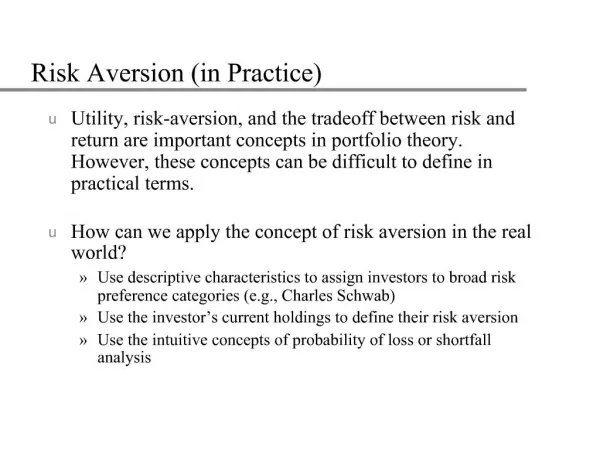

Our discussion so far has centered on understanding how people act when the outcomes of gambles have known objective probabilities. In reality, probabilities are rarely objectively known.

Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Our discussion so far has centered on understanding how people act when the outcomes of gambles have known objective probabilities. In reality, probabilities are rarely objectively known. To handle these situations, Savage (1964) develops a counterpart to expected utility known as subjective expected utility (SEU). Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 1 Tuesday, 10 June 20146:26 AM

Under certain axioms, preferences can be represented by the expectation of a utility function. This time weighted by the individual’s subjective probability assessment. Experimental work in the last few decades has been as unkind to SEU as it was to EU. The violations this time are of a different nature, but they may be just as relevant for financial economists. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 2

The classic experiment was described by Ellsberg (1961). Suppose that there are two urns, 1 and 2. Urn 1 also contains 100 balls, a mix of red and blue, but the subject does not know the proportion of each. Urn 2 contains a total of 100 balls, 50 red and 50 blue. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 3

Subjects are asked to choose one of the following two gambles, each of which involves a possible payment of $100, depending on the colour of a ball drawn at random from the relevant urn. a1: a ball is drawn from Urn 1, $100 if red, $0 if blue, a2: a ball is drawn from Urn 2, $100 if red, $0 if blue. Note your choice (Urn 1 mixed, Urn 2 50/50). Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 4

Subjects are then also asked to choose between the following two gambles: b1: a ball is drawn from Urn 1, $100 if blue, $0 if red, b2: a ball is drawn from Urn 2, $100 if blue, $0 if red. Note your choice (Urn 1 mixed, Urn 2 50/50). a2 is typically preferred to a1, while b2 is chosen over b1. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 5

These choices are inconsistent with SEU: the choice of a2 implies a subjective probability that fewer than 50% of the balls in Urn 1 are red, while the choice of b2 implies the opposite. (You could choose a1 and b2 or a2 and b1.) The experiment suggests that people do not like situations where they are uncertain about the probability distribution of a gamble. Such situations are known as situations of ambiguity, and the general dislike for them, as ambiguity aversion. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 6

An early discussion of this aversion can be found in Knight (1921), who defines risk as a gamble with known distribution and uncertainty as a gamble with unknown distribution, and suggests that people dislike uncertainty more than risk. SEU does not allow agents to express their degree of confidence about a probability distribution and therefore cannot capture such aversion. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 7

Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion Were you to accept the various forms of utility then Edwards and Fasolo (2001) tabulate nineteen steps to reaching a decision. 8.8 8

Ambiguity aversion appears in a wide variety of contexts. For example, a researcher might ask a subject for his estimate of the probability that a certain team will win its upcoming football match, to which the subject might respond 0.4. The researcher then asks the subject to imagine a chance machine, which will display 1 with probability 0.4 and 0 otherwise, and asks whether the subject would prefer to bet on the football game – an ambiguous bet – or on the machine, which offers no ambiguity. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 10

In general, people prefer to bet on the machine, illustrating aversion to ambiguity. Heath and Tversky (1991) argue that in the real world, ambiguity aversion has much to do with how competent an individual feels he is at assessing the relevant distribution. Ambiguity aversion over a bet can be strengthened by highlighting subjects’ feelings of incompetence, either by showing them other bets in which they have more expertise, or by mentioning other people who are more qualified to evaluate the bet (Fox and Tversky 1995). Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 11

Further evidence that supports the competence hypothesis is that in situations where people feel especially competent in evaluating a gamble, the opposite of ambiguity aversion, namely a “preference for the familiar”, has been observed. In the example above, people chosen to be especially knowledgeable about football often prefer to bet on the outcome of the game than on the chance machine. Just as with ambiguity aversion, such behaviour cannot be captured by SEU. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion 12

Other research establishes even more dramatically the role of reasons in decision-making. For instance, Tversky and Shafir (1992b) demonstrate that when people are searching, they do not merely search to find a high-value option — as assumed in conventional search theory — but also seem to search for a “reason” to end their search and make one particular choice. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 13

Tversky and Shafir (1992b) conducted experiments where subjects were asked either to choose among existing options, or to engage in a costly further search. In addition to a parallel experiment where subjects were asked to choose among gambles for real monetary stakes, a hypothetical apartment-search problem was posed. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 14

Shafir, Simonson, and Tversky (1993, pp. 19-20) summarise it as follows: Subjects were presented choices between hypothetical student apartments. Some subjects received the following problem: Conflict: Imagine that you face a choice between two apartments with the following characteristics: x) $290 a month, 25 minutes from campus y) $350 a month, 7 minutes from campus Both have one bedroom and a kitchenette. Note your choice. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 15

You can choose now between the two apartments or you can continue to search for apartments (to be selected at random from the list you received). In that case, there is some risk of losing one or both of the apartments you have found. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 16

Other subjects received a similar problem except that option y was replaced by option x’, to yield a Choice between: Dominance: x) $290 a month, 25 minutes from campus x′) $330 a month, 25 minutes from campus Both have one bedroom and a kitchenette. Note your choice. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 17

In both pairs of problems the choice between x and y - the conflict condition - is nontrivial because the x is better on one dimension and the y is better on the other. In contrast, the choice between x and x′ - the dominance condition – involves no conflict because the former strictly dominates the latter. Thus, while there is no obvious reason to choose one option over the other in the conflict condition, there is a decisive argument for preferring one of the two alternatives in the dominance condition. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 18

On average, subjects requested an additional alternative 64% of the time in the conflict condition (x,y), and only 40% of the time in the dominance condition (x,x’). Subjects’ tendency to search for additional options, in other words, was greater when the choice among alternatives was harder to rationalize, than when there was a compelling reason and the decision was easy. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 19

Why is the greater propensity to search further under the conflict condition (x,y) than under the dominance condition (x,x’) inconsistent with the utility-maximization model? Clearly U(x) > U(x′) for all subjects; it is indeterminate whether subjects would asses U(x) > U(y) or U(y) > U(x). Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 20

But if the decision to keep searching were based simply on some perceived continuation utility, V. Then any subject who would choose to stop under the dominance condition (x,x’), indicating that U(x) = V, would also choose to stop under the conflict condition (x,x’). Since they could always choose x where U(x) = V, or choose y, if U(y) > U(x), and do even better. The aggregate data, on seeking alternatives, reject the value-maximization hypothesis. What explains the pattern? Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 21

Tversky and Shafir (1992b) argue that the choice in the conflict condition (x,y) is difficult, and lacks a clear reason to choose x versus y - one is cheaper, the other is closer to campus, and it is hard to weigh these two attractive features. The dominance condition (x,x’), on the other hand, yields an obvious choice - x is just as close as x′ and is cheaper. This is a simple, obvious “reason” to choose x. The experiment suggests that search behaviour may be explained in part by the search for “reasons” rather than solely by the search for “value.” Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 22

Tversky and Shafir (1992a) show that, even if the information will not affect their decision, people are likely to delay decisions until they learn information that may affect their reason for making the decision. Students were asked, under different hypothetical scenarios, whether they would like to buy a bargain package for a Hawaii vacation during winter break. Prior to the vacation, they would find out whether they had passed or failed an important exam; if they failed, they would have to re-take the exam after winter break. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 23

Students were given the choice to buy the vacation package, not buy the package, or pay a non-refundable $50 fee to delay the decision. Three conditions were run: The students were told that a) They would not know whether they passed the exam when they had to choose - but if they bought the “delay option," they would then know whether they passed before they ultimately had to decide. b) They failed the exam, and would have to re-take after winter break. • They passed the exam. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 24

Of those asked in condition (a-don’t know), 32% chose to buy the package, 7% chose not to buy the package, and 61% chose to pay $50 to delay the decision. The delay option makes perfect sense: If your decision whether to take the vacation depends on whether or not you passed the exam, you may pay to wait to find out first. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 25

However, the results in conditions (b-fail) and (c-pass) rule out this explanation - only 31% in each group chose the delay option, and between 54% and 57% chose to buy the vacation (and, respectively, 16% and 12% chose not to take the package). That is, a majority of both passers and failers would choose to buy the vacation, yet without knowing, far fewer would choose to buy the vacation. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 26

Tversky and Shafir (1992a) argue that the key is that the reason for going on the vacation is very different depending on whether or not you pass - either you are going as a reward for a job well done, or to refresh yourself before retaking the exam. Like the apartment-search example, this example illustrates that people choose to defer decisions in part because they seek a clear-cut reason for their choice, not just to get the highest value out of their choice. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 27

In a similar vein, Redelmeier and Shafir (1995) report related results. Groups of physicians were randomly picked to respond to each of two hypothetical scenarios: A) Whether to prescribe one treatment in one category of treatments (e.g., medication) or one treatment in a second category (e.g., surgery), or B) Whether to prescribe one of two treatments in the first category, or one treatment in the second category. They found that more physicians chose the second category in Scenario B — apparently because the decision felt less arbitrary than choosing one of two, hard-to distinguish choices. Preferences In Ambiguity Aversion - Choices and Reasons 28

Who said, when describing Kahneman and Smith? Daniel Kahneman of Princeton University, USA“for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty”andVernon L. Smith of George Mason University, USA“for having established laboratory experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis, especially in the study of alternative market mechanisms”. Is This Area “Important” 29

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences on deciding that the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, 2002 be awarded to Kahneman and Smith. Advanced Information Is This Area “Important” 30

Traditionally, much of economic research has relied on the assumption of a “homo œconomicus” motivated by self-interest and capable of rational decision making. Economics has also been widely considered a non-experimental science, relying on observation of real-world economies rather than controlled laboratory experiments. Psychological and Experimental Economics 31

Nowadays, however, a growing body of research is devoted to modifying and testing basic economic assumptions; moreover, economic research relies increasingly on data collected in the lab rather than in the field. This research has its roots in two distinct, but currently converging, areas: the analysis of human judgment and decision-making by cognitive psychologists, and the empirical testing of predictions from economic theory by experimental economists. Psychological and Experimental Economics 32

Has integrated insights from psychology into economics, thereby laying the foundation for a new field of research. Kahneman’s main findings concern decision-making under uncertainty, where he has demonstrated how human decisions may systematically depart from those predicted by standard economic theory. Together with Amos Tversky (deceased in 1996), he has formulated prospect theory as an alternative, that better accounts for observed behaviour. Daniel Kahneman 33

Kahneman has also discovered how human judgment may take heuristic shortcuts that systematically depart from basic principles of probability. His work has inspired a new generation of researchers in economics and finance to enrich economic theory using insights from cognitive psychology into intrinsic human motivation. Daniel Kahneman 34

Has laid the foundation for the field of experimental economics. He has developed an array of experimental methods, setting standards for what constitutes a reliable laboratory experiment in economics. In his own experimental work, he has demonstrated the importance of alternative market institutions, e.g., how the revenue expected by a seller depends on the choice of auction method (see later). Vernon Smith 35

Smith has also spearheaded “wind-tunnel tests”, where trials of new, alternative market designs – e.g., when deregulating electricity markets – are carried out in the lab before being implemented in practice. His work has been instrumental in establishing experiments as an essential tool in empirical economic analysis. Not much psychology here! Vernon Smith 36

The four auction types are: 1. the English auction, where buyers announce their bids in an increasing order until no higher bid is submitted; 2. the Dutch auction, where a high initial bid is gradually lowered until a buyer melds his acceptance; 3. the first-price auction, with sealed bids, where the highest bidder pays his own bid to the seller; 4. the sealed-bid second-price auction, where the highest bidder pays the second highest bid. By The Way 37

Overconfidence Next Week 38