ESS 298: OUTER SOLAR SYSTEM

540 likes | 566 Vues

Discover the peculiarities of Triton, Neptune's largest moon, its unique orbit, surface composition, and geologically active features. Unravel the mysteries of its retrograde motion and young surface through scientific exploration.

ESS 298: OUTER SOLAR SYSTEM

E N D

Presentation Transcript

ESS 298: OUTER SOLAR SYSTEM Francis Nimmo Io against Jupiter, Hubble image, July 1997

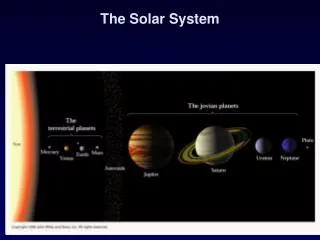

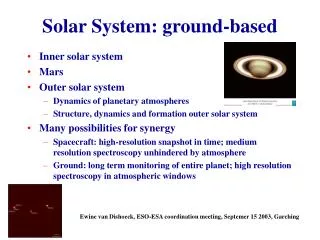

In this lecture • Triton (largest moon of Neptune) • Pluto/Charon • Kuiper Belt • Oort Cloud • Extra-solar planets • Where do we go from here? Reminder: computer writeup due this Thursday! ESS250?

Neptune system unusual • Uranus and Saturn both have interesting and diverse collections of moons • But the Neptune system is almost empty apart from . . . • Triton, which is retrograde (unique) Neptune system (schematic) Small, close moons Triton (retrograde) Nereid (small, eccentric, inclined, long way out) Neptune

25 15 Distance (Rp) 5 30 20 10 Where is Triton? Jupiter Neptune Triton No information on MoI – single flyby at 40,000 km (Voyager 2, 1989)

Triton’s peculiar orbit • It is retrograde – almost unique, especially amongst large bodies. Why? • Rotation is also synchronous (and retrograde) • There are no other sizeable bodies in the system 159o Neptune 29o Triton

What’s it like? • High albedo (0.85) so 38 K at the surface – coldest place in the solar system • Surface (based on terrestrial spectroscopy) consists of frozen N2 (at the polar cap), H2O, CO2, CO,CH4 • Thin (14 mbar) N2 atmosphere, hazes (presumably similar to Titan’s – CN compounds generated by photolysis) • Extreme seasonal variations • Surprisingly geologically interesting for such a small and cold body

Chemistry and Composition • At low temperatures characteristic of outer solar system, kinetics may mean C remains as CO not CH4 (see Week 1) – means less oxygen available to form water ice • Predicted rock/ice mass ratio in this case is 70/30 – which gives a density of ~2000 kg m-3, similar to that observed for both Triton and Pluto • In hotter nebula, CO-> CH4, oxygen then available to form water ice, rock/ice mass ratio 50/50, giving a density of ~1500 kg m-3 • Detection of CO is also consistent with low temperatures during formation of Triton (and Pluto) • Gives a clue as to where Triton formed

Seasonal cycles (1) • Neptune has a period of 164 yrs and an obliquity of 29o • Triton has an inclination of 21o and a period of 0.016 yrs • Triton’s orbit precesses with a period of 688 yrs • So the angle between Triton’s pole and the Sun varies very widely (see diagram below) 29o Neptune 21o Triton 21o Voyager observations 164 yrs From Cruikshank, Solar System Encyclopedia

Seasonal cycles (2) • At the time of the Voyager encounter, Triton was in a maximum southern summer • Models suggest that N2 was subliming from the S pole and accumulating to the N • These models also predicted winds flowing N from the S pole (observationally confirmed) • Over 688 years, more energy is deposited at the equator than either pole • So the existence of high albedo, presumably volatile deposits, covering most of the S hemisphere is embarrassing to the modellers

500 km • Possible cryovolcanic region • Smooth plains indicate low viscosity • Ammonia-water melt has viscosity comparable to basalt Triton’s peculiar surface • Very few impact craters -> young (~100 Myrs) • “Cantaloupe terrain” • Plains suggestive of cryovolcanism • Tectonic features • Geologically active! Cantaloupe terrain

Active Geysers (!) • Only recognized after the event • Presumably powered by N2 (sublimates at 2o above mean surface temperature) • Directions of dark streaks suggest winds blowing away from the pole (as expected) ~100 km Activity of this kind is unlikely to be able to explain the absence of big impact craters, again indicating that Triton’s surface is very young Particles falling out 8 km Dark streak developing

ridge Cantaloupe terrain 220 km Tectonic features Scale bars are 2 km for Europa and 40 km for Triton The characteristic spacing of cantaloupe terrain must be telling us something. Is it the signature of thermal convection or is it some kind of Rayleigh-Taylor instability? Salt domes on Earth are examples of the latter, and generate similar features. Ridge morphology on Triton resembles that on Europa (though widths are very different). Is a similar kind of process at work on the two bodies?

Cratering Statistics • Strong apex-antapex asymmetry • Larger than predicted by models of NSR (!) • May be partly caused by partial resurfacing (e.g. cantaloupe terrain) • Not well understood From Zahnle et al., Icarus 2001

Several puzzles and a solution • 1) Why is Triton’s orbit retrograde? • 2) Why are there so few satellites in the system? • 3) Why is the surface so young? TRITON WAS CAPTURED • 1) Collision and capture of an initially heliocentric body is essentially the only way to explain retrograde orbit • 2) Triton’s orbit will have adjusted following capture, sweeping up any pre-existing moons • 3) Capture can occur at any time (and releases enormous amounts of energy when it occurs)

Triton Triton’s orbit circularizes due to tides Triton on heliocentric orbit Other satellites scattered outwards by close encounters as Triton’s orbit evolves Inoffensive prograde satellites Neptune Inoffensive prograde satellite Hypothetical scenario See e.g. Stern and McKinnon, A.J., 2001 An alternative is that capture occurred due to gas drag. Why is this scenario less likely?

So what? • Gigantic tidal dissipation (see next slide) • Circularization explains absence of other bodies • Collision explains Nereid’s orbit (small, very far out, high e and i – due to perturbations as Triton’s orbit circularized) • Young surface age suggests (relatively) recent collision – how likely is this? • Improbable events can happen – what’s another example of an improbable event? • Where did Triton come from? (see later)

Tidal Heating • Orbit was initially very eccentric and with a large semi-major axis • Tidal dissipation within Triton will have reduced both e and a and generated heat • DT ~ GMp/aCp ~105 K ! (Where’s this from?) • Capture resulted in massive melting • Perhaps this melting caused compositional variations which allowed the cantaloupe terrain to form? • Heating means differentiation almost inevitable

1352 km 950 km, 0.4 GPa 600 km , 1.5 GPa 3.0 GPa Internal Structure • Density = 2050 kg m-3, MoI unknown • Chemical arguments suggest 70/30 rock/ice ratio (see earlier slide) • Volatiles except H2O are assumed to be minor constituents of interior • Assume differentiated due to tidal heating ice Hypothetical internal structure of Triton (see e.g. McKinnon et al., Triton, Ariz. Univ. Press, 1995) rock iron

Comets and their Origins • Two kinds of comets • Short period (<200 yrs) and long period (>200 yrs) • Different orbital characteristics: ecliptic Short period: prograde, low inclination Long period: isotropic orbital distribution • This distribution allows us to infer the orbital characteristics of the source bodies: • S.P. – relatively close (~50 AU), low inclination (Kuiper Belt) • L.P. – further away (~104 AU), isotropic (Oort Cloud)

Short-period comets • Period < 200 yrs. Mostly close to the ecliptic plane (Jupiter-family or ecliptic, e.g. Encke); some much higher inclinations (e.g. Halley) • Most are thought to come from the Kuiper Belt, due to collisions or planetary perturbations • Form the dominant source of impacts in the outer solar system • Is there a shortage of small comets/KBOs? Why? From Weissmann, New Solar System From Zahnle et al. Icarus 2003

Scattered Disk Objects Kuiper Belt • ~800 objects known so far, occupying space between Neptune (30 AU) and ~50 AU • Largest objects are Pluto, Charon, Quaoar (1250km diameter), 2004 DW (how do we measure their size?) • Two populations – low eccentricity, low inclination (“cold”) and high eccentricity, high inclination (“hot”) “hot” ECCENTRICITY “cold” Brown, Phys. Today 2004 • Total mass small, ~0.1 Earth masses • Difficult to form bodies as large as 1000 km when so little total mass is available (see next slide) • A surprisingly large number (few percent) binaries • See Mike Brown’s article in Physics Today Apr. 2004 and Alessandro Morbidelli’s review in Science Dec. 2004

Building the Kuiper Belt From Stern A.J. 1996 Different lines are for different mean random eccentricities • Planetesimal growth is slower in outer solar system (why?) • Calculations suggests that it is not possible to grow ~1000km size objects in the Kuiper belt with current mass distribution Solar system age Growth time Disk mass (ME) • How might we avoid this paradox (see next slide)? • 1) Kuiper Belt originally closer to Sun • 2) We are not seeing the primordial K.B.

“Hot” population Present day Planetesimals transiently pushed out by Neptune 2:1 resonance “Cold” population J N U S Neptune stops at original edge 3:2 Neptune resonance (Pluto) 2:1 Neptune resonance See Gomes, Icarus 2003 and Levison & Morbidelli Nature 2003 Kuiper Belt Formation Early in solar system Ejected planetesimals (Oort cloud/Scattered Disk Objects) “Hot” population Initial edge of planetesimal swarm J N S U 18 AU 30 AU 48 AU

What does this explain? • Two populations (“hot” and “cold”) • Transported by different mechanisms (scattering vs. resonance with Neptune) • “Cold” objects are red and (?) smaller; “hot” objects are grey and (?) larger • Hot population formed (or migrated) closer to Sun • Formation and (current) position of Neptune • Easier to form it closer in; current position determined by edge of initial planetesimal swarm (why should it have an edge?) • Small present-day total mass of Kuiper Belt for the size of objects seen there • It was initially empty – planetesimals were transported outwards

Binaries • A few percent KBO’s are binaries, mostly not tightly bound (separation >102 radii) – Pluto/Charon an exception. Why are binaries useful? • Pluto has two extra satellites (Weaver et al., Nature 2006) • How did these binaries form? • Collisions not a good explanation – low probability, and orbits end up tightly bound (e.g. Earth/Moon) • A more likely explanation is close passage (<~1 Hill sphere), with orbital energy subsequently reduced by interaction with swarm of smaller bodies (Goldreich et al. Nature 2002). Implies that most binaries are ancient (close passage more probable) • Any interesting consequences of capture?

Long-period comets • Periods > 200 yrs (most only seen once) e.g. Hale-Bopp • Source is the Oort Cloud, perturbations due to nearby stars (one star passes within 3 L.Y. every ~105 years). Such passages also randomize the inclination/eccentricity • Distances are ~104 A.U. and greater • Maybe 10-102 Earth masses • Sourced from originally scattered planetesimals • Objects closer than 20,000 AU are bound tightly to the Sun and are not perturbed by passing stars • Periodicity in extinctions(?)

Oort Cloud • What happens to all the planetesimals scattered out by Jupiter? They end up in the Oort cloud (close-in versions are called Scattered Disk Objects) • This is a spherical array of planetesimals at distances out to ~200,000 AU (=3 LY), with a total mass of 10-102 Earths • Why spherical? Combination of initial random scattering from Jupiter, plus passages from nearby stars • Forms the reservoir for long period comets Oort cloud (spherical after ~5000 AU) Saturn Earth Pluto Kuiper Belt 100,000 AU 10,000 AU 100 AU 1,000 AU 1 AU 10 AU After Stern, Nature 2003

2003 VB12 (Sedna) and 2003 UB313 • Sedna discovered in March 2004, most distant solar system object ever discovered • a=480 AU, e=0.84, period 10,500 years • Perihelion=76 AU so it is a scattered disk object (not a KBO) • Radius ~ 1000 km (how do we know?) • Light curve suggests a rotation rate of ~20 days (slow) • This suggests the presence of a satellite (why?), but to date no satellite has been imaged (why not?) • 2003 UB313 is another SDO which is interesting mainly because at ~3000 km it is bigger than Pluto (how do we know?) (Bertoldi et al. Nature 2006)

Kuiper Belt and SDO’s Plutinos Twotinos SDO’s Kuiper Belt

Pluto and Charon • Pluto discovered in 1930, Charon not until 1978 (indirectly; can now be imaged directly with HST) • Orbit is highly eccentric – sometimes closer than Neptune (perihelion in 1989) • Orbit is in 3:2 resonance with Neptune, so that the two never closely approach (stable over 4 Gyr) • Charon is a large fraction (12%) of Pluto’s mass and orbits at a distance of 17 Pluto radii • Charon’s orbit is almost perpendicular to the ecliptic; Pluto’s rotation pole presumably also tilted with respect to its orbit (i.e. it has a high obliquity) • Pluto-Charon is (probably) a doubly synchronous system

Discoveries • Neptune’s existence was predicted on the basis of observations of Uranus’ orbit (by Adams and LeVerrier) • Percival Lowell (of Mars canals infamy) “predicted” the existence of Pluto based on Neptune’s orbit • Pluto was discovered at Lowell’s observatory in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh (who looked at 90 million star images, over 14 years) Blink-test discovery of Pluto • Charon was discovered by James Christy at the US Naval Observatory in 1978. This was good timing . . .

A lucky coincidence Pluto’s rotation pole • Once every 124 years, Pluto and Charon mutually occult each other. Why is this important? • Charon discovered in 1978; mutual occultation occurred in 1988 • This event allowed much more precise determinations of the sizes of both bodies Pluto’s orbital path View from Earth. Note that Charon’s orbit is inclined to Pluto’s (and to the ecliptic). From Binzel and Hubbard, in Pluto and Charon, Univ. Ariz. Press, 1997

Pluto and Charon • Pluto’s orbit: a=39.5 AU, orbital period 248 years, e=0.25, i=17o , rotation period 6.4 days • Charon’s orbit: a=19,600km (17 Rp), period=6.4 days, e=?, i=0o

Compositions • Pluto’s surface composition very similar to Triton: CH4 (more than Triton), N2, CO, water ice, no CO2 detected as yet • Charon’s surface consists of mostly water ice • Charon is significantly darker than Pluto, suggesting the presence of other (undetected) species From Cruikshank, in New Solar System CH4 CO

Pluto’s atmosphere • It has one! ~10 microbars, presumably N2 (volatile at surface temp. of 40 K) • First detected by occultation in 1988 (perihelion) • Atmospheric pressure is determined by vapour pressure of nitrogen (strongly temperature-dependent) • More recent detection (Elliot et al. Nature 2003) shows that the atmosphere has expanded (pressure has doubled) despite the fact that Pluto is now moving away from the Sun. Why? • Possibly because thermal inertia of near-surface layers means there is a time-lag in response to insolation changes

Pluto/Charon Origins • Compositional similarities to Triton suggest same ultimate source – Kuiper Belt • Pluto’s current orbit is probably due to perturbations by Neptune as N moved outwards (recall the 3:2 resonance) • Charon is most likely the result of a collision. Clues: • Its orbital inclination (and Pluto’s rotation) strongly suggest an impact (c.f. Neptune) • The angular momentum of the system (see next slide) • Comparable size of two bodies also suggestive (c.f. Earth-Moon system) • Are the compositional differences between Pluto and Charon the result of the impact? • If correct, then neither Pluto nor Charon are pristine Kuiper Belt objects (e.g. tidally heated)

New Horizons • An ambitious mission to fly-by Pluto/Charon and investigate one or more KBOs (PI Alan Stern, managed by APL) • Launch date Jan 2006, arrives Pluto 2015 • Powered by RTG (politically problematic . . . ) • Very risk-averse (almost every system is duplicated) • Science limited by high fly-by speed (but we know very little about Pluto/Charon right now)

Extra-Solar Planets • A very fast-moving topic • How do we detect them? • What are they like? • Are they what we would have expected? (No!)

How do we detect them? • The key to most methods is that the star will move (around the system’s centre of mass) in a detectable fashion if the planet is big and close enough • 1) Pulsar Timing • 2) Radial Velocity pulsar A pulsar is a very accurate clock; but there will be a variable time-delay introduced by the motion of the pulsar, which will be detected as a variation in the pulse rate at Earth planet Earth star Spectral lines in star will be Doppler-shifted by component of velocity of star which is in Earth’s line-of-sight. This is easily the most common way of detecting ESP’s. planet Earth

How do we detect them? (2) • 2) Radial Velocity (cont’d) Earth The radial velocity amplitude is given by Kepler’s laws and is i Does this make sense? Ms Mp Note that the planet’s mass is uncertain by a factor of sin i. The Ms+Mp term arises because the star is orbiting the centre of mass of the system.Present-day instrumental sensitivity is about 3 m/s; Jupiter’s effect on the Sun is to perturb it by about 12 m/s. From Lissauer and Depater, Planetary Sciences, 2001

How do we detect them? (3) • 3) Occultation • Planet passes directly in front of star. Very rare, but very useful because we can: • Obtain M (not M sin i) • Obtain the planetary radius • Obtain the planet’s spectrum (!) • Only one example known to date. Light curve during occultation of HD209458. From Lissauer and Depater, Planetary Sciences, 2001 • 4) AstrometryNot yet demonstrated. • 5) MicrolensingDitto. • 6) Direct ImagingBrown dwarfs detected.

Note the absence of high eccentricities at close distances – what is causing this effect? What are they like? • Big, close, and often highly eccentric – “hot Jupiters” • What are the observational biases? HD209458b is at 0.045 AU from its star and seems to have a radius which is too large for its mass (0.7 Mj). Why? Jupiter Saturn From Guillot, Physics Today, 2004

What are they like (2)? • Several pairs of planets have been observed, often in 2:1 resonances • (Detectable) planets seem to be more common in stars which have higher proportions of “metals” (i.e. everything except H and He) There are also claims that HD179949 has a planet with a magnetic field which is dragging a sunspot around the surface of the star . . . Sun Mean local value of metallicity From Lissauer and Depater, Planetary Sciences, 2001

eccentricity distance giant planet (observed) star Laughlin, Chambers and Fischer Simulations of solar system accretion • Computer simulations can be a valuable tool This is one of an extra-solar system (47 UMa). It turns out that the giant planet “b” makes it hard to form a terrestrial planet at ~1 AU.

Puzzles • 1) Why so close? • Most likely explanation seems to be inwards migration due to presence of nebular gas disk (which then dissipated) • The reason they didn’t just fall into the star is because the disk is absent very close in, probably because it gets cleared away by the star’s magnetic field. An alternative is that tidal torques from the star (just like the Earth-Moon system) counteract the inwards motion • 2) Why the high eccentricities? • No-one seems to know. Maybe a consequence of scattering off other planets during inwards migration? • 3) How typical is our own solar system? • Not very, on current evidence

Consequences • What are the consequences of a Jupiter-size planet migrating inwards? (c.f. Triton) • Systems with hot Jupiters are likely to be lacking any other large bodies • So the timing of gas dissipation is crucial to the eventual appearance of the planetary system (and the possibility of habitable planets . . .) • What controls the timing? • Gas dissipation is caused when the star enters the energetic T-Tauri phase – not well understood (?) • So the evolution (and habitability) of planetary systems is controlled by stellar evolution timescales – hooray for astrobiology!

Where do we go from here? • Ground-based observations are amazingly good, and will only get better • Next generation of space-based telescopes – SIRTF already in place, Terrestrial Planet Finders are on the drawing boards • Missions? Depends on the vagaries of NASA, but New Horizons is probably secure, and maybe one (several?) JIMO-class missions will fly . . . • Outer solar system has 3 disadvantages: • Long transit timescales (ion drives?) • Some kind of nuclear power-source required • Prospects for life are dim

Summing Up - Themes • Accretion (timescales, energy deposition, gas accumulation . . .) • Volatiles (gas giants, antifreeze effect, atmospheres etc.) • Energy transfer (insolation, convection, radioactive heating, tidal dissipation . . .) • Tides (satellite evolution, disk clearing, geological features . . .) • Diversity – no-one would have predicted such variability (and this solar system may not even be typical)

Summing Up - Lessons • Timescales and lengthscales both longer than inner solar system (accretion period, Hill sphere etc.) • The early outer system was very different from today: • Giant planets were in a different place • Satellite orbits have evolved • Large population of planetesimals (now scattered) • Single most important event was Jupiter’s formation • Scattering of planetesimals; asteroid gaps etc. • Earlier formation would have increased inwards migration (why?) • Other solar systems look very different to our own • What is typical, and why? • Extra-solar planets will continue to be a major focus of research