DNA: Structure and Replication

460 likes | 565 Vues

Explore DNA structure, genome sizes, and replication processes. Learn about nucleotides, base pairing, and the Watson-Crick model. Understand circular and linear DNA replication mechanisms. Uncover the mysteries of genome size variations in different organisms.

DNA: Structure and Replication

E N D

Presentation Transcript

6 DNA Structure, Replication, and Manipulation

Genome Size • The genetic complement of a cell or virus constitutes its genome • In eukaryotes, this term is commonly used to refer to one complete haploid set of chromosomes, such as that found in a sperm or egg • The C-value = the DNA content of the haploid genome • The units of length of nucleic acids in which genome sizes are expressed : • kilobase (kb) 103 base pairs • megabase (Mb) 106 base pairs

Genome Size • Viral genomes are typically in the range 100–1000 kb: Bacteriophage MS2, one of the smallest viruses, has only four genes in a single stranded RNA molecule of about 4000 nucleotides (4kb) • Bacterial genomes are larger, typically in the range 1–10 Mb: The chromosome of Escherichia coli is a circular DNA molecule of 4600 kb.

Genome Size • Eukaryotic genomes are typically in the range 100–1000 Mb: The genome of a fruit fly, Drosophilamelanogaster is 180 Mb • Among eukaryotes, genome size often differs tremendously, even among closely related species

The C-value Paradox • Genome size among species of protozoa differ by 5800-fold, among arthropods by 250-fold, fish 350-fold, algae 5000-fold, and angiosperms 1000-fold. • The C-value paradox: Among eukaryotes, there is no consistent relationship between the C-value and the metabolic, developmental, or behavioral complexity of the organism • The reason for the discrepancy is that in higher organisms, much of the DNA has functions other than coding for the amino acid sequence of proteins

DNA: Chemical Composition • DNA is a linear polymer of four deoxyribonucleotides • Nucleotides composed of 2'- deoxyribose (a five-carbon sugar), phosphoric acid, and the four nitrogen-containing bases denoted A, T, G and C Fig. 6.3

DNA: Chemical Composition • Two of the bases, A and G, have a double-ring structure; these are called purines • The other two bases, T and C, have a single-ring structure; these are called pyrimidines Fig. 6.2

DNA Structure • The nucleotides are joined to form a polynucleotide chain, in which the phosphate attached to the 5 ' carbon of one sugar is linked to the hydroxyl group attached to the 3' carbon of the next sugar in line • The chemical bonds by which the sugar components of adjacent nucleotides are linked through the phosphate groups are called phosphodiesterbonds

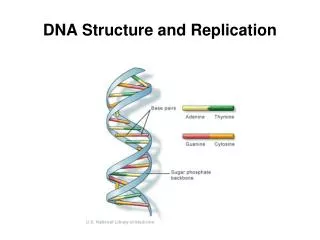

DNA Structure • The duplex molecule of DNA consists of two polynucleotide chains twisted around one another to form a right-handed helix in which the bases form hydrogen bonds Adenine pairs with thymine; guanine with cytosine A hydrogen bond is a weak bond The stacking of the base pairs on top of one another also contribute to holding the strands together The paired bases are planar, parallel to one another, and perpendicular to the long axis of the double helix.

DNA Structure • The backbone of each polynucleotide strand consists of deoxyribose sugars alternating with phosphate groups that link 5 ' carbon of one sugar to the 3' carbon of the next sugar in line • The two polynucleotide strands of the double helix run in opposite directions • The paired strands are said to be antiparallel Fig. 6.7

DNA: Watson-Crick Model 3-D structure of the DNA molecule: • Double helix forms major and minor grooves • Diameter of the helix = 20 Angstroms • Each turn of the helix = 10 bases = 34 Angstroms

DNA Replication Watson-Crick model of DNA replication: • Hydrogen bonds between DNA bases break to allow strandseparation • Each DNA strand is a templatefor the synthesis of a new strand • Template (parental) strand determines the sequence of bases in the new strand (daughter)= complementarybase pairing rules Fig. 6.8

DNA Replication • In 1958 M. Meselson and F. Stahl showed that DNA replication is semiconservative: The parental strands remain intact and serves as a template for a new strand

Circular DNA Replication • Autoradiogram of the intact replicating circular chromosome of E. coli shows that • DNA synthesis is bidirectional • Replication starts from a single site called origin of replication (OR) • The region in which parental strands are separating and new strands are being synthesized is called a replication fork Fig. 6.12

Rolling Circle Replication • Some circular DNA molecules of a number of bacterial and eukaryotic viruses, replicate by a different mode called rolling-circle replication . • One DNA strand is cut by a nuclease to produce a 3’-OH extended by DNA polymerase • The newly replicated strand is displaced from the template strand as DNA synthesis continues • Displaced strand is template for complementary DNA strand

Replication ofLinear DNA • The linear DNA duplex in a eukaryotic chromosome also replicates bidirectionally • Replication is initiated at many sites along the DNA • Multiple initiation is a means of reducing the total replication time

Replication ofLinear DNA • In eukaryotic cell, origins of replication are about 40,000 bp apart, which allows each chromosome to be replicated in 15 to 30 minutes. • Because chromosomes do not replicate simultaneously, complete replication of all chromosomes in eukaryotes usually takes from 5 to 10 hours.

DNA Synthesis • One strand of the newly made DNA is synthesized continuously = leadingstrand • The other, lagging strand is made in small precursor fragments = Okazaki fragments • The size of Okazaki fragments is 1000–2000 base pairs in prokaryotic cells and 100–200 base pairs in eukaryotic cells.

DNA vs. RNA • DNA sugar = deoxyribose RNA sugar = ribose • RNA contains the pyrimidine uracil (U) in place of thymine (T) • DNA is double-stranded RNA is single-strand • Short RNA fragment serves as a primer to initiate DNA synthesis at origins of replication

DNA Replication: Proteins • Gyrase = Topoisomerase II introduces a double-stranded break ahead of the replication fork and swivels the cleaved ends to relieve the stress of helix unwinding • Helicase unwinds DNA at replication fork to separate the parental strands • Single-strand binding protein (SSB) stabilizes single strands of DNA at replication fork

DNA Replication: Proteins • Multienzyme complex calledprimosomeinitiates strand synthesis by forming RNA primer • The enzyme DNA polymerase forms the the phosphodiester bond between adjacent nucleotides in a new DNA acid chain in 5’ to 3’ direction • DNA polymerase has a proofreading function that corrects errors in replication

DNA Replication: Proteins • The final stitching together of the lagging strand must require • Removal of the RNA primer • Replacement with a DNA sequence • Joining where adjacent DNA fragments • Primer removal and replacement in E. coli is accomplished by a special DNA polymerase (Pol I) that removes one ribonucleotide at a time

DNA Replication: Proteins • In eukaryotes, the primer RNA is removed as an intact unit by a protein called RPA (replicationprotein A) • DNA ligase catalyzes the formation of the final bond connecting the two precursor

Nucleic Acid Hybridization • DNA denaturation: Two DNA strands can be separated by heat without breaking phosphodiester bonds • DNA renaturation= hybridization:Two single strands that are complementary or nearly complementary in sequence can come together to form a different double helix • Single strands of DNA can also hybridize complementary sequences of RNA

Restriction Enzymes • Restriction enzymes cleave duplex DNA at particular nucleotide sequences • The nucleotide sequence recognized for cleavage by a restriction enzyme is called the restriction site of the enzyme • In virtually all cases, the restriction site of a restriction enzyme reads the same on both strands A DNA sequence with this type of symmetry is called a palindrome

Restriction Enzymes • Many restriction enzymes all cleave their restriction site asymmetrically—at a different site on the two DNA strands • They create sticky ends = each end of the cleaved site has a single-stranded overhang that is complementary in base sequence to the other end • Some restriction enzymes cleave symmetrically— at the same site in both strands • They yield DNA fragments that have blunt ends

Restriction Enzymes • Because of the sequence specificity, a particular restriction enzyme produces a unique set of restriction fragments for a particular DNA molecule. • Another enzyme will produce a different set of restriction fragments from the same DNA molecule. • A map showing the unique sites of cutting of a particular DNA molecule by restriction enzyme is called a restriction map

Southern Blot Analysis • DNA fragments on a gel can often be visualized by staining with ethidium bromide,a dye which binds DNA • Particular DNA fragments can be isolated by cutting out the small region of the gel that contains the fragment and removing the DNA from the gel. • Specific DNA fragments are identified by hybridization with a probe = a radioactive fragment of DNA or RNA • Southern blot analysis is used to detect very small amounts of DNA or to identify a particular DNA band by DNA-DNA or DNA-RNA hybridization

Southern Blot Analysis Steps in Southern blot procedure: • DNA is digested by restrictionenzymes • DNA fragments are separated by gel electrophoresis • DNA is transferred from gel to hybridization filter = blot procedure • DNA denatured to produce single-stranded DNA

Southern Blot Analysis • Filter is mixed with radiolabeled single-stranded DNA or RNA probe at high temperatures which permit hybridization = formation of hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs • DNA bands hybridized to a probe are detected by X-ray film exposure

Polymerase Chain Reaction • Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) makes possible the amplification of a particular DNA fragment • Oligonucleotide primers that are complementary to the ends of the target sequence are used in repeated round of denaturation, annealing, and DNA replication • The number of copies of the target sequence doubles in each round of replication, eventually overwhelming any other sequences that may be present

Polymerase Chain Reaction • Special DNA polymerase is used in PCR = Taq polymerase isolated from bacterial thermophiles which can withstand high temperature used in procedure • PCR accomplishes the rapid production of large amounts of target DNA which can then be identified and analyzed

DNA Sequence Analysis • DNA sequence analysis determines the order of bases in DNA • The dideoxy sequencing method employs DNA synthesis in the presence of small amounts of fluorescently labeled nucleotides that contain the sugar dideoxyribose instead of deoxyribose Fig. 6.29

DNA Sequencing: Dideoxy Method • Modified sugars cause chain termination because it lacks the 3’-OH group, which is essential for attachment of the next nucleotide in a growing DNA strand • The products of DNA synthesis are then separated by electrophoresis. In principle, the sequence can be read directly from the gel

DNA Sequencing: Dideoxy Method • Each band on the gel is one base longer than the previous band • Each didyoxynucleotide is labeled by different fluorescent dye • G, black; A, green; T, red; C, purple • As each band comes off the bottom of the gel, the fluorescent dye that it contains is excited by laser light, and the color of the fluorescence is read automatically by a photocell and recorded in a computer