Individual Behavior and Social Structures

190 likes | 360 Vues

Individual Behavior and Social Structures. Shyam Sunder Whitney Humanities Center October 3, 2012. Science of Individual Behavior?. Recent focus on individual behavior confronts economics with a challenge shared among the social sciences

Individual Behavior and Social Structures

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Individual Behavior and Social Structures Shyam Sunder Whitney Humanities Center October 3, 2012

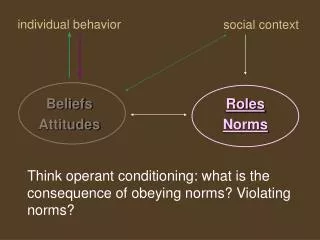

Science of Individual Behavior? • Recent focus on individual behavior confronts economics with a challenge shared among the social sciences • As a science, we seek general laws that apply across time and space, trying to emulate physics, chemistry and biology • Perfecting the scope and power of general laws of human behavior does not leave much room for individual choice • What does it mean to have a science of individual human behavior? Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Dilemma of Social Sciences • Do we give up free will and personal responsibility, and treat humans like other objects of science? • Drop the “social” and become a plain vanilla science • Or, do we abandon the search for universal laws, the pretense of being a science, embrace human free will and unending variation of behavior, and try to join the humanities • Either way, there will be no social science left • Is there a way to keep “social” and “science” together? Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Science • Identifies laws of nature: valid everywhere and all the time • Regularities of nature captured in known and knowable relationships among observable elements (including stochastic) • Helps understand, explain, and predict • If I know X, can I form a better idea of whether Y was, is or will be? • Objects of science have no free will • A photon does not pause to enjoy the scenery • A marble rolling down the side of a bowl does not wonder about whether it will come to stop at the bottom of the bowl, but it always does Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Social Science • Object of social sciences is us, who have the power and ability to do what we wish, beyond what is predictable on the basis of our circumstances, beliefs, and tendencies • Ability to rise above our circumstances is a part of our identity and concept of self, distinguished from inanimate objects of science • To claim the status of a science, we look for laws that describe our behavior • But stripped of freedom to act, and being subject to such laws, encroaches on our self-image Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Mismatch of Science and Personal Responsibility • Objects of science can have no personal responsibility • They do not choose to do anything • They are merely driven by their circumstances, like a piece of paper blown by gusts of wind, or a piece of rock rolling down the hill under force of gravity in the path of an oncoming car • Is an abused child who grows up to be an abusive parent responsible for his behavior? • Science and personal responsibility do not mix well Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Problem of Building a Theory of Choice • This challenge of social sciences is exemplified in difficulties of building a theory of choice • From science end: axiomatization of human choice as a function of innate preferences: people choose what they prefer • How do we know what they prefer? Look at what they choose • The circularity between preferences and choice might be avoided if there were permanency and consistency in preference-choice relationship across diverse contexts • One could observe choice in one context, tentatively infer the preferences from these observations, and assuming consistent preferences, predict choice in other contexts • Unfortunately, half-a-century of research has yielded little predictability of choice from inferred preferences across contexts (Friedman and Sunder 2011) • Individual human behavior appears to be unmanageably rowdy to capture in a stable set of laws • Humanists can hardly be surprised (if they pay any attention at all to choice theory) Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Laws with Predictive Content in Social Sciences • Simple economic theory: point of intersection of demand and supply determines price and allocations • Economists’ have had deep faith in theory, nobody knew for sure that it works • Until Vernon Smith’s (1962) experiment in his classroom (where motivated students traded) double auction provided the evidence that the law of supply and demand has reasonable predictive power • Predictive power at aggregate level, although individual behavior is not predictable • But does the result arise from human intelligence and striving, or is a property of the market mechanism? Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Smith (1962) Chart 1 Sunder, Structure and Behavior

A Serendipitous Discovery • Stock market crash of 1987 • Most reports blamed it to program trading • Why would introduction of computer traders cause the stock market to crash? • Created a course on program trading to learn • Human traders, and program traders • Students asked for my own program to compete with theirs’ • My problem as an instructor Sunder, Structure and Behavior

What Makes the Difference Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Why Equilibrium without Individual Optimization • Why do the markets populated with simple budget-constrained random bid/ask strategies converge close to Walrasian prediction in price and achieve close to 100% allocative efficiency • No memory, learning, adaptation, maximization, even bounded rationality Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Inference • The structure, not the behavior of participants, accounts for the first order magnitude of outcomes in competitive settings • Computers and experiments with simple agents opened a new window into a previously inaccessible aspect of economics • Ironically, it was not through computers’ celebrated optimization capability • Instead, through deconstruction of human behavior • Isolating the aggregate (social) level consequences of simple or arbitrarily chosen classes of individual behavior Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Optimization Principle • In physics: marbles and photons “behave” but are not attributed any intention or purpose • Yet, optimization principle has proved to be an excellent guide to how physical and biological systems as a whole behave • At multiple hierarchical levels--brain, ganglion, and individual cell—physical placement of neural components appears consistent with a single, simple goal: minimize cost of connections among the components. The most dramatic instance of this "save wire" organizing principle is reported for adjacencies among ganglia in the nematode nervous system; among about 40,000,000 alternative layout orderings, the actual ganglion placement in fact requires the least total connection length. In addition, evidence supports a component placement optimization hypothesis for positioning of individual neurons in the nematode, and also for positioning of mammalian cortical areas. • Perhaps we can use a similar approach in study of social institutions Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Optimization Principle Imported into Economics • Humans and human systems as objects of economic analysis • Conflict between mechanical application of optimization principle and our self-esteem (free will) • Optimization principle interpreted as a behavioral principle, shifting focus from aggregate to individual behavior • Cognitive science: we are not good at optimizing • Social institutions may have evolved to make up our cognitive limitations Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Focusing on Properties of Social Institutions • Significant parts of social sciences, and a large part of economics, are concerned with aggregate level outcomes of socio-economic institutions • Institutions themselves do not need to be ascribed intentionality or free will • Characteristics of social institutions can be analyzed by methods of science Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Individuals and Institutions • I do not have much to add on the most complex problem of examining individual behavior • It seems that we shall continue to examine ourselves and our behavior using both humanities as well as science perspectives, without reconciling the two into a single logical structure • But properties of institutions can be identified by methods of science Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Structural Properties of Social Institutions • Economics can be usefully thought of as a behavioral science in the sense physicists study the “behavior” of marbles and photons • Individual behavior is likely to remain as a shared domain of humanities and sciences • Modeling specific behaviors as software agents in the context of specific economic institutions allows us to identify aggregate level properties of social institutions (as in the case of ZI agents) Sunder, Structure and Behavior

Thank You Please send comments to Shyam.sunder@yale.edu