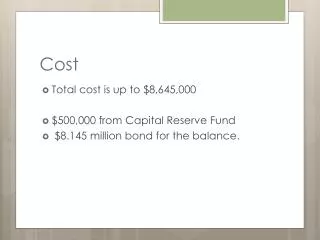

Cost

670 likes | 957 Vues

Cost. Economic Cost. Economists consider both explicit costs and implicit costs. Explicit costs are a firm’s direct, out-of-pocket payments for inputs to its production process during a given time period such as a year.

Cost

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Economic Cost • Economists consider both explicit costs and implicit costs. • Explicit costs are a firm’s direct, out-of-pocket payments for inputs to its production process during a given time period such as a year. • These costs include production worker’s wages, manager’s salaries, and payments for materials.

Economic Cost • However, firms use inputs that may not have an explicit price. • These implicit costs include the value of the working time of the firm’s owner and the value of other resources used but not purchased in a given period.

Economic Cost • The economic costs or opportunity cost is the value of the best alternative use of a resource. • The economic or opportunity cost includes both explicit and implicit costs. • If a firm purchases and uses an input immediately, that input’s opportunity cost is the amount the firm pays for it. • If the firm uses an input from its inventory, the firm’s opportunity cost is not necessarily the price it paid for the input years ago. • Rather, the opportunity cost is what the firm could buy or sell that input for today.

Economic Cost • The classic example of an implicit opportunity cost is captured in the phrase “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” • Suppose that your friend offer to take you to lunch tomorrow. • You know that they’ll pay for the meal, but you also know that this lunch will not really be free for you. • Your opportunity cost for the lunch is the best alternative use of your time. • This might be studying, working at a job or watching TV.

Economic Cost • If you start your own firm, you should be very concerned about opportunity costs. • Suppose that your explicit cost is P40,000, including the rent for you work space, the cost of materials, and the wage payments to your employees. • Because you do not pay yourself a salary – instead, you keep any profit at the year’s end – the explicit cost does not include the value of your time.

Economic Cost • Your firm’s full economic cost is the sum of of the explicit cost plus the opportunity value of your time. • If the highest wage you could have earned working for some other firm is P25,000, your full economic cost is P65,000. • If your annual revenue is P60,000 after you pay your explicit cost of P40,000, you keep P20,000 at the end of the year. • The opportunity cost of your time P25,000, exceeds P20,000, so you can earn more working for someone else.

Capital Cost • Determining the cost of capital, such as land or equipment, requires special considerations. • Capital is a durable good: a good that is usable for years. • Two problems arise in measuring the cost of capital. • Allocating Capital Costs over Time • Actual and Historical Costs

Allocating Capital Costs over Time • Capital may be rented or purchased. • For example, a firm may rent a truck for P200 a month or buy it outright for P18,000. • If the firm rents the truck, the rental payment is the relevant opportunity cost. • If the firm buys the truck, the firm may expense the cost by recording the full P18,000 when the purchase is made, or may amortize the cost by spreading the P18,000 over the life of the truck.

Allocating Capital Costs over Time • An economists amortizes the cost of the truck on the basis of its opportunity cost at each moment of time, which is the amount that the firm could charge others to rent the truck. • Regardless of whether the firm buys or rents the truck, an economist views the opportunity cost of this capital good as a rent per time period: the amount the firm will receive if it rents its truck to others at the going rental rate.

Actual and Historical Costs • A piece of capital may be worth much more or much less today than when it was purchased. • To maximize profit, a firm must properly measure the cost of a piece of capital – its current opportunity cost of the capital good – and not what the firm paid for it – its historical cost. • Suppose that a firm paid P30,000 for a piece of land that it can resell for only P20,000.

Actual and Historical Costs • Also suppose that is uses the land itself and that the current value of the land to the firm is only P19,000. • Should the firm use the land or sell it? • The firm should ignore how much it paid for the land in making its decision. • Because the value of the land to the firm, P19,000, is less than the opportunity cost of the land, P20,000, the firm can make more money by selling the land.

Actual and Historical Costs • The firm’s current opportunity cost of capital may be less than what it paid if the firm cannot resell the capital. • A firm that bought a specialized piece of equipment that has no alternative use cannot resell the equipment. • Because the equipment has no alternative use, the historical cost of buying that capital is a sunk cost: an expenditure that cannot be recovered.

Actual and Historical Costs • Because this equipment has no alternative use, the current or opportunity cost of the capital is zero. • In short, when determining the rental value of capital, economists use the opportunity value and ignore the historical price.

Short-Run Costs • A firm’s cost rises as the firm increases its output. • A firm cannot vary some of its input, such as capital, in the short run. • As a result, it is usually more costly for a firm to increase output in the short run than in the long run when all inputs can be varied.

Short-Run Cost Measures • To produce a given level of output in the short run, a firm incurs costs for both its fixed and variable inputs. • A firm’s fixed cost (F) is its production expense that does not vary with output. • The fixed cost includes the cost of inputs that the firm cannot practically adjust in the short run, such as land, a plant, large machines, and other capital good.

Short-Run Cost Measures • A firm’s variable cost (VC) is the production expense that changes with the quantity of output produced. • The variable cost is the cost of the variable inputs – the inputs the firm can adjust to alter its output level, such as labor and materials. • A firm’s cost (or total cost, C) is the sum of a firm’s variable cost and fixed cost: • Because variable cost changes with the level of output, total cost also varies with the level of output.

Short-Run Cost Measures • A firm’s marginal cost(MC) is the amount by which a firm’s cost changes if the firm produces one more unit of output. The marginal cost is • Because only the variable cost changes with output, we can also define marginal cost as the change in variable cost from a small increase in output.

Short-Run Cost Measures • The average fixed cost (AFC) is the fixed cost divided by the units of output produced • The average fixed cost falls as output rises because the fixed cost is spread over more units: • It approaches zero as the output level grows very large.

Short-Run Cost Measures • The average variable cost (AVC) is the variable cost divided by the units of output produced • Because the variable cost increases with output, the average variable cost may either increase or decrease as output rises.

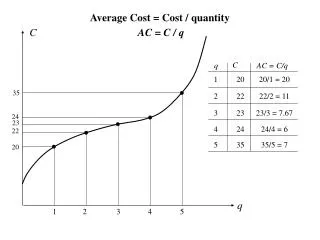

Short-Run Cost Measures • The average cost (AC) – or average total cost – is the total cost divided by the units of output produced: • Because total cost equals variable cost plus fixed cost, C = VC + F, when we divide both sides of the equation by q, we learn that

Short-Run Cost Measures Illustration: A manufacturing plant has a short-run cost function of What is the firm’s short-run fixed cost and variable cost function? Derive the formulas for its marginal cost, average fixed cost, average variable cost, and average cost.

Short-Run Cost Measures The fixed cost is F = 450, the only part that does not vary with q. The variable cost function is the part of the cost function that varies with q. Differentiating the short-run cost function or variable cost function, we find that

cost C A 115 1,725 1 VC 80 B 1 800 450 F q 0 10 15 cost per unit MC 125 a AC 115 AVC b 80 45 AFC q 0 10 15

Production Functions and the Shape of Cost Curves • The production function determines the shape of a firm’s cost curves. • The production function shows the amount of inputs needed to produce a given level of output. • The firm calculates its cost by multiplying the quantity of each input by its price and summing.

Production Functions and the Shape of Cost Curves • If a firm produces output using capital and labor and its capital is fixed in the short run, the firm’s variable cost is its cost of labor. • Its labor cost is the wage per hour, w, times the number of hours of labor, L, employed by the firm: VC = wL • If input prices are constant, the production function determines the shape of the variable cost curve. • Because capital does not vary, we can write the production function as

Production Functions and the Shape of Cost Curves • By inverting, we know that the amount of labor we need to produce any given amount of output is L = g-1(q). • If the wage of labor is w, the variable cost function is VC(q) = wL = wg-1(q) • Similarly, the cost function is

Production Functions and the Shape of Cost Curves • In the short run, when the firm’s capital is fixed, the only way the firm can increase its output is to use more labor. • If the firm increases its labor enough, it reaches the point of diminishing marginal returns to labor, where each extra worker increases output by a smaller amount. • If the production function exhibits diminishing marginal returns, then the variable cost rises more than in proportion as output increases.

Shape of the Marginal Cost Curves • The marginal cost is the change in variable cost as output increases by one unit: • In the short run, capital is fixed, so the only way a firm can produce more output is to use extra labor. • The extra labor required to produce one more unit of output is

Shape of the Marginal Cost Curves • The extra labor costs the firm w per unit, so the firm’s cost rises by • As a result, the firm’s marginal cost is • The marginal cost equals the wage times the extra labor necessary to produce one more unit of output.

Shape of the Marginal Cost Curves • Since the marginal product of labor, the amount of extra output produced by another unit of labor, holding other input fixed is • Thus, the extra labor needed to produce one more unit of output is • So the firm’s marginal cost is

Shape of the Marginal Cost Curves • The marginal cost equals the wage divided by the marginal product of labor. • If it takes four extra hours of labor services to produce one more unit of output, the marginal product of an hour is ¼. • Given a wage of P5 an hour, the marginal cost of one more unit of output is P5 divided by ¼, or P20.

Shape of the Average Cost Curves • For the firm whose only variable input is labor, variable cost is wL, so average variable cost is • Because the average product of labor is • Average variable cost is the wage divided by the average product of labor

Long-Run Costs • In the long run, a firm adjusts all its inputs so that its cost of production is as low as possible. • The firm can change its plant size, design and build new machines, and otherwise adjusts inputs that were fixed in the short run. • The rent of F per month that a restaurant pays is a fixed cost because it does not vary with the number of meals served. • In the short run, this fixed cost is sunk. • The firm must pay F even if the restaurant does not operate.

Long-Run Costs • In the long run, this fixed cost is avoidable. • The firm does not have to pay this rent if it shuts down. • The long run is determined by the length of the rental contract, during which time the firm is obligated to pay rent. • All inputs can be varied in the long run, so there are no long-run fixed costs (F = 0). • As a result, the long-run total cost equals the long-run variable cost: C = VC.

Long-Run Costs • In the long run, the firm chooses how much labor and capital to use, whereas in the short run, when capital is fixed, it chooses only how much labor to use. • As a consequence, the firm’s long-run costs is lower than its short-run cost of production if it has to use the ‘wrong’ level of capital in the short run.

Input Choice • A firm can produce a given level of output using many different technologically efficient combinations of inputs, as summarized by an isoquant. • From among the technologically efficient combinations of inputs, a firm wants to choose the particular bundle with the lowest cost of production, which is the economically efficient combination of inputs.

Input Choice • To do so, the firm combines the information about technology from the isoquant with information about the cost of labor and capital

Isocost Line • The cost of producing a given level of output depends on the price of labor and capital. • The firm hires L hours of labor services at a wage of w per hour, so its labor cost is wL. • The firm rents K hours of machine services at a rental rate of r per hour, so its capital cost is rK. • The firm’s total cost is the sum of its labor and capital costs: • The firm can hire as much labor and capital as it wants at these constant input prices.

Isocost Line • The firm can use many combinations of labor and capital that cost the same amount. • These combinations of labor and capital are plotted on an isocost line, which indicates all the combinations of inputs that require the same (iso) total expenditure (cost). • Along an isocost line, cost is fixed at a particular level. • We can write the equation for isocost line with cost fixed at

Isocost Line • Which we can rewrite as • By differentiating with respect to L, we find that the slope of any isocost line is • Thus, the slope of the isocost line depends on the relative prices of the inputs.

K w = 24, r = 8 C = 3,000 375 C = 2,000 250 C = 1,000 125 0 41.67 83.33 125 L

Minimizing Cost • By combining the information about costs that is contained in the isocost lines with information about efficient production that is summarized by an isoquant, a firm chooses the lowest-cost way to produce a given level of output.

K q = 100 w = 24, r = 8 C = 3,000 375 y 303 C = 2,000 250 C = 1,000 125 x 100 z 28 0 24 41.67 50 83.33 116 125 L

Using Calculus to Minimize Cost • The firm is minimizing cost subject to the information in the production function contained in the isoquant expression: • The corresponding Lagrangian problem is

Using Calculus to Minimize Cost • The first-order conditions are

Using Calculus to Minimize Cost • By rearranging terms, we obtain • We find that cost is minimized where the factor price ratio equals the ratio of the marginal products.

Maximizing Output • We could equivalently examine the dual problem of maximizing output for a given level of cost, • The first-order conditions are