Learning Across the Lifespan

240 likes | 473 Vues

Learning Across the Lifespan. How what we know about learning and how it applies to creating effective learning experiences for our varied audiences. To contemplate…. You cannot teach a man anything; you can only help him find it within himself. - Galileo

Learning Across the Lifespan

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Learning Across the Lifespan How what we know about learning and how it applies to creating effective learning experiences for our varied audiences

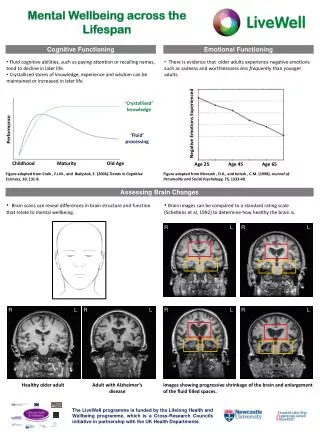

To contemplate… You cannot teach a man anything; you can only help him find it within himself.- Galileo It is little short of a miracle that modern methods of instruction have not completely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry.- Albert Einstein In the heyday of the psychometric and behaviorist eras, it was generally believed that intelligence was a single entity that was inherited; and that human beings - initially a blank slate - could be trained to learn anything, provided that it was presented in an appropriate way. Nowadays an increasing number of researchers believe precisely the opposite; that there exists a multitude of intelligences, quite independent of each other; that each intelligence has its own strengths and constraints; that the mind is far from unencumbered at birth; and that it is unexpectedly difficult to teach things that go against early 'naive' theories of that challenge the natural lines of force within an intelligence and its matching domains. - Howard Gardner

Jean Piaget, 1897-1980 • Intelligence develops in a series of stages that are related to age and are progressive because one stage must be accomplished before the next can occur. • With each stage the child forms a view of reality for that age period. At the next stage, the child must keep up with earlier level of mental abilities to reconstruct concepts. • Intellectual development as an upward expanding spiral in which children must constantly reconstruct the ideas formed at earlier levels with new, higher order concepts acquired at the next level. • Perception is shaped and limited by experience. Knowledge is acquired in a continuous process of accommodating prior expectations and beliefs to new realities learned through interactive experiences. • Learning involves conflict between a person’s conception of reality and new encounters with the real. • Assimilation is interpreting the external world in terms of our current schemes or presently available ways of thinking about things, building additional understanding and reinforcing known things. • Accommodation is a kind revision to take into account newly understood properties, changing and refining structures to achieve a better adaptive fit with the experience. • Cognition proceeds from the concrete to the abstract.

Piaget’s stages of development • Preoperational stage: from ages 2 to 7 (magical thinking predominates. Acquisition of motor skills). Egocentrism begins strongly and then weakens. Children cannot use logical thinking. • Concrete operational stage: from ages 7 to 12 (children begin to think logically but are very concrete in their thinking). Children can now think logically but only with practical aids. They are no longer as egocentric. • Formal operational stage: from age 12 onwards (development of abstract reasoning). Children develop abstract thought and can easily conserve and think logically in their mind.

Lev Vygotsky, 1896-1934 • Individual cognition develops as a result of interactions in the social life of the individual. • Cannot isolate individual processes from social processes: must understand an individual’s social relationships to understand the learning process. People spend the majority of their time in social interaction. • All learning is built upon previous learning, not just of the individual, but of the entire society in which that individual lives. • people use language not only for social communication but also to guide, plan, and monitor their activity in a self-regulatory way. • self regulatory language known as private speech, children use this kind of language in their thinking. • language mediates social interaction and cognitive activity between individuals as well as within individuals. • Children’s learning takes place within a “zone of proximal development,” the distance between a child’s “actual developmental” level in being able to solve a problem independently, and the higher level of “potential development,” if they were to solve a problem with adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. • In this “space” between actual and potential, there is a social mediation process, scaffolding, which is the creation of processes and ideas between two or more individuals.

Howard Gardner, 1943- • Howard Gardner initially formulated a list of seven intelligences. His listing was provisional. The first two have been typically valued in schools; the next three are usually associated with the arts; and the final two are what Howard Gardner called 'personal intelligences' (Gardner 1999: 41-43). • Linguistic intelligence: sensitivity to spoken and written language, the ability to learn languages, and the capacity to use language to accomplish certain goals. This intelligence includes the ability to effectively use language to express oneself rhetorically or poetically; and language as a means to remember information. Writers, poets, lawyers and speakers are among those that Howard Gardner sees as having high linguistic intelligence. • Logical-mathematical intelligence: analyze problems logically, carry out mathematical operations, and investigate issues scientifically. In Howard Gardner's words, it entails the ability to detect patterns, reason deductively and think logically. This intelligence is most often associated with scientific and mathematical thinking. • Musical intelligence: skill in the performance, composition, and appreciation of musical patterns. It encompasses the capacity to recognize and compose musical pitches, tones, and rhythms. According to Howard Gardner musical intelligence runs in an almost structural parallel to linguistic intelligence. • Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence: using one's whole body or parts of the body to solve problems. It is the ability to use mental abilities to coordinate bodily movements. • Spatial intelligence: recognize and use the patterns of wide space and more confined areas. • Interpersonal intelligence: the capacity to understand the intentions, motivations and desires of other people. It allows people to work effectively with others. Educators, salespeople, religious and political leaders and counsellors all need a well-developed interpersonal intelligence. • Intrapersonal intelligence: the capacity to understand oneself, to appreciate one's feelings, fears and motivations. In Howard Gardner's view it involves having an effective working model of ourselves, and to be able to use such information to regulate our lives.

John Dewey (1859-1952) • Dewey was known as the “father of experiential education” • learning was active and schooling unnecessarily long and restrictive. His idea was that children came to school to do things and live in a community which gave them real, guided experiences which fostered their capacity to contribute to society. For example, Dewey believed that students should be involved in real-life tasks and challenges • math could be learned by learning proportions in cooking or figuring out how long it would take to get from one place to another by mule • history could be learned by experiencing how people lived, geography, what the climate was like, and how plants and animals grew • Dewey had a gift for suggesting activities that captured the center of what his classes were studying. • Dewey's education philosophy helped forward the "progressive education" movement, and spawned the development of "experiential education" programs and experiments. • Dewey's philosophy still lies very much at the heart of many bold educational experiments, such as Outward Bound.

Constructivism: a philosophy of learning Principles of learning Learners construct knowledge for themselves---each learner individually (and socially) constructs meaning. There is no knowledge independent of the meaning attributed to experience (constructed) by the learner, or community of learners. 1. Learning is an active process in which the learner uses sensory input and constructs meaning out of it. Learning is not the passive acceptance of knowledge which exists "out there" but involves the learners engaging with the world. 2. People learn to learn as they learn: learning is constructing meaning and constructing systems of meaning. For example, if we learn the chronology of dates of a series of historical events, we are simultaneously learning the meaning of a chronology. Each meaning we construct makes us better able to give meaning to other sensations which can fit a similar pattern. 3. Constructing meaning is mental: it happens in the mind. Physical actions, hands-on experience may be necessary for learning, especially for children, but it is not sufficient; we need to provide activities which engage the mind as well as the hands. (Dewey called this reflective activity.)

Four orientations to Learning Four orientations to learning (after Merriam and Caffarella 1991: 138)

Children • Concrete learners • Learn by doing • Captive audiences • Experiences revolve around world they know: highly personal, family, friends, school • Difficulties with abstractions such as time

Adolescents • Individuation from families; independence • Concerned with identity: who am I in the world? • Adults in body, firmly entrenched in family • Interested in the big topics, like sex, death, meaning of life • Peer interaction extremely important • Technology

Adults • Young, middle, older adult groups • “passionate and purposeful” learners • Personally motivated by experience and living in an historic period • Leisure time, free time • Not a captive audience – visit the museum of their own volition