Evolutionary Psychology Workshop 9: Female Aggression .

150 likes | 312 Vues

Evolutionary Psychology Workshop 9: Female Aggression . Learning Outcomes. 1 . Conduct a small-scale study assessing possible sex differences in aggression. You should test 2 males and 2 females.

Evolutionary Psychology Workshop 9: Female Aggression .

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Learning Outcomes. • 1. Conduct a small-scale study assessing possible sex differences in aggression. You should test 2 males and 2 females. • 2. Collate the results from the whole group and discuss the findings in relation to the relevant literature. • 3. Critically discuss the methodology in such a technique. • 4. Discuss issues raised by a paper concerning sex differences in aggression.

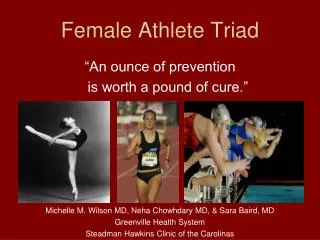

Background. • Female aggression has been viewed as a gender-incongruent aberration. • Campbell (1999) however argued that certain aspects of female aggression are just as adaptive as certain kinds of male aggression. • Females face the brunt of childrearing and so the survival of the mother is of major importance to the wellbeing of the child (particularly in infancy). • Eg in the Ache of Paraguay where the mother dies in the first year of the infants life, the subsequent mortality rate is 100% (Hill & Hurtado, 1996). • Females therefore have a greater tendency than males to protect their own lives and this will have enhanced their reproductive success.

Evidence: • Females display more 'anxious' behaviour particularly with regards health and personal welfare issues. • Certain phobias (animals, dangerous places) are more common in women. • Women are less likely to engage in sensation-seeking behaviours. • Women have lower rates of accidental injury. • Women are less likely to take drugs. • Women report higher levels of fear of crime. • Women rate the importance of health higher than men, know more about health issues and are more likely to adopt preventative care. • Women overestimate the dangers of a potential aggressive encounter.

Resources. • Campbell (2001) argued that while males compete with one another for dominance and its rewards, females compete with one another for resources (ie other males) which can directly enhance their reproductive success. • We would thus expect the severity of competition to be related to the availability of resource-rich males - where males are few then female competition and aggression should be higher. • This also influences female mating strategy - when males are scarce (and much in demand) then females have little option but to engage in short-term relationships. • Where well-resourced males are abundant, female competition will take the form of epigamic display - (advertising of qualities considered desirable by the opposite sex).

Female Aggression in Context. • Women are significantly more likely to be attacked by another woman (generally an acquaintance) than a man. • In the USA, Campbell et al., (1998) found that out of 297 female-female fights, 121 were concerned with men and 67 were about subsistence concerns (food, money, domestic goods etc). • Normally though, the fear of direct physical assault means that females are less likely to form dominance hierarchies which would entail direct physical aggression to develop and maintain. • They are thus much more likely to form small co-operative groups (often with other female relatives).

Evidence. • When placed into groups girls cooperate whilst boys compete. • Girls who show strong competitive or dominance behaviours are rejected by their peer group. • Boys use direct commands while girls use polite persuasion. • Girls are very concerned to develop cohesion and shared norms within the group. • Collaborative interchanges are more common in female groups while domineering exchanges are more common in male groups. • Males are more likely to adopt an autocratic leadership role and accentuate differences between individuals and groups.

Female Aggression is Indirect. • Males are more likely to favour direct physical or verbal aggression. • Such aggression would not be adaptive for females as they may get injured. • Female aggression is therefore more likely to be 'indirect', ie it takes the form of social manipulation where the 'attacker' may hide their identity by: • Spreading nasty gossip. • Shunning other members of the group. • Using any influence in the group to get other members ostracised.

Evidence. • Girls are much more likely to exclude newcomers than are boys. • Girls are more likely to destroy an adversary's property or tell tales on them. • Girls are more likely to use social ostracism and manipulation of others opinions. • Girls who bully other girls are more likely to use indirect aggression rather than direct aggression.

Does This Explain the Following? • Female criminal behaviour comes close to that of males only in larceny/theft, particularly where direct confrontations are absent (ie credit card fraud as opposed to mugging). • Where female-female physical violence does occur, it is most often triggered by competition over scarce resources (usually men) and is most common between current wife/girlfriend and ex wife/girlfriend. • In areas where adequate males are scarce (in prison, unemployed or drug-addicted) females will choose males who display their resources or their dominance (expensive cars, flashy clothes, jewellery, gun possession. • Female-female homicide is very rare and women are much less likely to use weapons when aggressing.

Female-Female Aggression. • According to Campbell et al., (1998), female-female aggression occurs most often in lower-class females aged 15-24 who generally know one another. • The most frequent trigger for female-female aggression is competition for the attention of men and triggered by insults that slight the others sexual reputation. • In their study they addressed 2 questions: • 1. Is intra-female aggression most common at younger ages? • 2. Is intra-female aggression linked to mate shortage and male resource scarcity?

Campbell et al., (1998) Study. • They analysed female-female assaults in Massachusetts during 1994 (482 in total). They found the following: • The majority of these cases were committed by females <24 years old. • The number of female-female assaults rose with increased dependency on welfare. • Male unemployment was unrelated to female-female aggression. • Women committed more property crime (fraud, shoplifting) and were more likely to engage in prostitution.

Task. • Give out the Buss & Perry (1992) aggression questionnaire to 2 males and 2 females. • We will collect data from the whole group and compare our data with the standardised scores. • While you are waiting to input your data you may wish to complete 2 questionnaires related to aggression (assertiveness and arguing style) on-line: • http://discoveryhealth.queendom.com/access_assertiveness.html • http://discoveryhealth.queendom.com/access_arguing_style.html

References. • Buss, A.H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63: 452-459. • Campbell, A. (1999). Staying alive: evolution, culture, and women's intrasexual aggression. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 22: 203-252. • Campbell, A.(2001). Women and crime an evolutionary approach. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 6: 481-497. • Campbell, A., Muncer, S., & Bibel, D. (1998). Female-female criminal assault: an evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 35: 413-428. • Hill, K., & Hurtado, A.M. (1996). Ache Life History. Aldine de Gruyter.