Understanding Tropical Cyclones: Structure, Formation, and Impact

250 likes | 369 Vues

This section provides a comprehensive overview of tropical cyclones, including their definitions, formation conditions, climatology, and impacts. Tropical cyclones, known regionally as hurricanes or typhoons, can cause significant destruction and loss of life. The discussion covers the climatological aspects of these storms, including seasonality, necessary warm ocean waters, and the role of angular momentum. Additionally, it highlights the devastating effects of cyclones, with historical examples illustrating their potential for damage and loss.

Understanding Tropical Cyclones: Structure, Formation, and Impact

E N D

Presentation Transcript

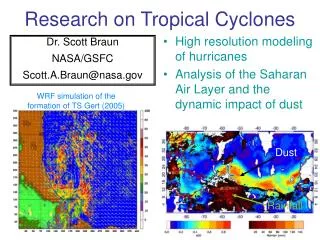

Section 5: Tropical Cyclones 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Climatology and Structure 5.3 Angular Momentum and Thermal Wind 5.4 Theories for Genesis 5.5 Maximum Potential Intensity 5.6 Tracks 5.7 Hot Issues Resources: http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/tcfaq/tcfaqHED.html http://wind.mit.edu/~emanuel/ Many Images in this lecture are courtesy of Kerry Emanuel

5.1 Introduction: Definitions The terms "hurricane" and "typhoon" are regionally specific names for a strong "tropical cyclone". A tropical cyclone is the generic term for a non-frontal synoptic scale low-pressure system over tropical or sub-tropical waters with organized convection (i.e. thunderstorm activity) and definite cyclonic surface wind circulation (Holland 1993).

5.1 Introduction: Definitions Tropical cyclones with maximum sustained surface winds of less than 17 m/s (34 kt, 39 mph) are called “tropical depressions”. Once the tropical cyclone reaches winds of at least 17 m/s (34 kt, 39 mph) they are typically called a “tropical storm” and assigned a name. If winds reach 33 m/s (64 kt, 74 mph)), then they are called: "hurricane" (the North Atlantic Ocean, the Northeast Pacific Ocean east of the dateline, or the South Pacific Ocean east160E) "typhoon" (the Northwest Pacific Ocean west of the dateline) "severe tropical cyclone" (the Southwest Pacific Ocean west of 160E or Southeast Indian Ocean east of 90E) "severe cyclonic storm" (the North Indian Ocean) "tropical cyclone" (the Southwest Indian Ocean) (Neumann 1993)

5.1 Introduction: Definitions The USA utilizes the Saffir-Simpson hurricane intensity scale (Simpson and Riehl 1981) for the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific basins to give an estimate of the potential flooding and damage to property given a hurricane's estimated intensity: Saffir-Simpson Scale Note : Classification by central pressure was ended in the 1990s, and wind speed alone is now used. These estimates of the central pressure that accompany each category are for reference only.

5.1 Introduction: Tropical Cyclones are Important! "The death toll in the infamous Bangladesh Cyclone of 1970 has had several estimates, some wildly speculative, but it seems certain that at least 300,000 people died from the associated storm tide [surge] in the low-lying deltas." (Holland 1993) The largest damage caused by a tropical cyclone as estimated by monetary amounts has been Hurricane Katrina (2005) as it struck the Bahamas, Florida and Louisiana: US $40.6 Billion in insured losses, and an estimated $81 billion in total losses. However, if one normalizes hurricane damage by inflation, wealth changes and coastal county population increases, then Katrina is only the third worst, after the 1926 Great Miami Hurricane and the lethal 1900 Galveston Hurricane. If the 1926 storm hit in 2005, it is estimated that it would cause over $140 billion in damages, and the 1900 storm about $92 billion (Pielke, Gratz, Landsea, Collins, Saunders, Musulin 2006).

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Regions of Formation • low latitudes, 5-20o (not at the equator): f important • none in SE Pacific or S. Atlantic: SSTs important • more appear in the Pacific than in the Atlantic: SSTs important

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Seasonality Most Tropical Cyclones occur in Summer and early Fall

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Tracks Tropical cyclones generally recurve polewards from their easterly track

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Conditions for occurrence • Gray (1979) • Warm ocean waters (of at least 26.5°C [80°F], some say 26oC) throughout a sufficient depth (unknown how deep, but at least on the order of 50 m [150 ft]), and area. • Why is this important? • Warm waters are necessary to fuel the heat engine of the tropical cyclone. Warm SSTs allows cumulus convection to reach the tropopause and give maximum warming in the troposphere.

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Conditions for occurrence 2. A minimum distance of at least 500 km [300 mi] from the equator. Why is this important? Must have background rotation (f > 0) large enough to convert inflow to tangential flow (cf conservation of angular momentum). Consider vorticity equation.

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Conditions for occurrence Gray (1979) 3. Low values (less than about 10 m/s [20 kts 23 mph]) of vertical wind shear between the surface and the upper troposphere. Why is this important? From thickness considerations the minimum surface pressure is related to the mean temperature of the column above. If shear tilts the column of warm air over then the surface pressure will rise. Other possible reasons include “ventilation” effects or more simply understood “shearing out”. Some shear may actually be beneficial!

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Conditions for occurrence Gray (1979) 4. A pre-existing near-surface disturbance with sufficient vorticity. Why is this important? Tropical cyclones cannot be generated spontaneously. They must be triggered. What can serve as a seedling? Easterly wave, MCSs, Upper-level midlatitude troughs. Problem: these are often cold core!

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Conditions for occurrence Gray (1979) 4. A pre-existing near-surface disturbance with sufficient vorticity. Why is this important? Tropical cyclones cannot be generated spontaneously. They must be triggered. What can serve as a seedling? Easterly wave, MCSs, Upper-level midlatitude troughs. Problem: these are often cold core! Why is this important?

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Conditions for occurrence In Summary: Environment: Need significant f, SSTs and low shear. Seedling: Need finite amplitude disturbance.

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Conditions for occurrence More Conditions from Gray (1979) 5. Decrease of equivalent potential temperature with height. Large CAPE? Controversial. See WISHE theory later! 6. Relatively moist layers near the mid-troposphere (5 km [3 mi]). Weak or no downdrafts. See boundary layer discussion later. 5 and 6 are mutually exclusive!

5.2 Climatology and Structure: Observed Structure The Thetae Structure Key is the strong surface radial gradient of thetae Mature hurricanes are nearly moist adiabatic in the eye wall. Thus the strong surface radial gradient in thetae leads to the large gradient in T in the troposphere. Hydrostatically this leads to the large surface pressure gradient and associated large surface winds. Compare with large-scale circulations discussed earlier. For large-scale circulations variations in thetae were linked to variations in SST For TC circulations variations in thetae are linked to variations in moisture content of the boundary layer. Surface fluxes are crucial!

5.3 Angular Momentum and Thermal Wind See Notes